“They chant for cars, don’t they?” I have heard this at least a dozen times already. The man sitting across the table from me is a Zen Buddhist monk. A practitioner in his early forties and a fifteen-year veteran of the New York Buddhist scene, this is all he knows about Soka Gakkai International (SGI for short), the largest, most racially and ethnically diverse Buddhist organization in America and, with twelve million members in 186 countries worldwide and a full-time representative to the United Nations, the first global Buddhist presence in history. But he isn’t alone in his ignorance. An organization with community centers in seventy major cities, a weekly newspaper, and its own four-year university can hardly be called insular; nevertheless, SGI is routinely marginalized in books on Buddhism in America, remains underrepresented at major conferences, and seldom appears in the pages of American Buddhist magazines (including this one).

“Yeah, that’s right,” I reply. “But why stop at cars? Why not washing machines, next month’s rent, or affordable health care for your child?”

I consider going on to name a few more of the things I have heard Soka Gakkai members chant for—everything from baby formula to world peace—but I can tell he isn’t really interested. A pilgrim on America’s Upper Middle Way to enlightenment, he doesn’t believe in chanting for worldly benefits. It’s hard to know what specifically he finds laughable about chanting for cars, but the fact remains, he can laugh about it. Even now, as a monk, when he no longer has need of one, a car is something he can afford to take for granted.

Chanting for a better car, a new job, even a mate, has long been the hallmark of SGI, especially at the beginning stages of practice, when new members are asked to try chanting nam-myoho-renge-kyo(“Devotion to the Lotus of the Wonderful Law”) for whatever they want. This is sometimes cited as a reason that SGI-USA has attracted so many African Americans (as many as 20,000 by some estimates, roughly twenty percent of its membership)—the idea that a religion offering the promise of worldly benefits is more innately attractive to minorities.

Like most convenient explanations, this one is partially true. African Americans and other minorities are, statistically speaking, still less likely to experience material abundance than their white counterparts, and so it is conceivable (though hardly a given) that they might be more concerned with worldly benefits, at least on the level of meeting immediate daily needs. But like most easy answers to complex questions, this one is essentially a kind of stereotype, the purpose of which is to avoid confronting the real reasons for SGI’s phenomenal success in attracting diversity—and conversely, the reasons virtually every other Buddhist organization in America has failed to do so. For that is the simple truth of it: Soka Gakkai has attracted real diversity among its membership, and no other American Buddhist group has.

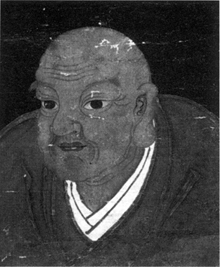

All sects of Nichiren Buddhism, including SGI, trace their origins to the teachings of the thirteenth-century Japanese monk for whom they are named. The son of a fisherman, Nichiren (1222-1282) was a religious reformer whose uniquely prophetic style of Buddhism challenged the established religious structure of medieval Japan, in which Buddhism had become a tool to maintain social order in the hands of an imperial and intellectual elite. Twice attacked, twice exiled, and once sentenced to death for his uncompromising views, Nichiren taught a self-empowered, egalitarian form of Buddhism based on the teachings of the Lotus Sutra. Nichiren’s Buddhism stood in stark contrast to the complicated state-supported Buddhism of the established schools, and to the distinctly otherworldly orientation of Pure Land. First of all, his teachings were simple: he insisted that his disciples could attain Buddhahood in this lifetime simply by chanting nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Secondly, they were practical: he instructed them to seek proof of the teachings in this world, not the next. This emphasis on inner transformation, validated by concrete changes in one’s life, gave Nichiren Buddhism the distinctive practical cast that it retains to the present day, most notably in its modern lay movements, the Soka Gakkai and its smaller cousin, Rissho Kosei-kai.

Soka Kyoiku Gakkai (literally, “Society for Value-Creating Education”) was founded as a lay movement of the Nichiren Shoshu sect of Buddhism in 1930 by Tsunesaburo Makiguchi (1871-1944), an educational reformer whose emphasis on independent thinking over rote learning, and self-motivation over blind obedience eventually led him into conflict with the militarist government of wartime Japan. In 1943, along with his protégé, Josei Toda (1900-1958), Makiguchi was imprisoned as a “thought criminal,” and died in prison a year later, in 1944. Toda emerged from prison in 1945 amidst the confusion and poverty of postwar Japan. He was determined to rebuild the Soka Gakkai, whose membership had dwindled to almost nothing. Drawing inspiration from a mystical revelation he experienced while in solitary confinement, Toda transformed the Soka Gakkai from a small educational reform movement into a socially engaged organization that promoted Nichiren Buddhism as a path of self-empowerment and social transformation, a message that was particularly welcome to the more disenfranchised members of Japanese society. By the time of his death, in 1958, the membership of Soka Gakkai had grown to nearly a million.

In 1960, when Toda’s successor, Daisaku Ikeda, arrived in America to establish the first overseas Soka Gakkai organization, he met with the Japanese wives of U.S. servicemen who had returned to the states following World War II. His advice to them was simple: Learn English, get a driver’s license, and become a U.S. citizen. And, of course, true to Nichiren Shoshu tradition, do shakubuku—convert others to the faith. Among current members of SGI, these Japanese war brides have achieved almost legendary status. “I have nothing but admiration for those women,” says Ronnie Smith, in 1998 the first male African American to be appointed a Senior Vice General Director of SGI-USA. He recalls:

They didn’t know much English at all, but through this practice they had transformed their lives and learned to make the impossible possible, blossoming like a lotus in the midst of muddy water. And so they got out there on the street to spread that message. And, really, their lives were the message, and it was all about world peace and the nobility of Buddhist work in the real world.

Another senior SGI member recalls those early evangelists with a touch of humor: “We called their technique ‘smile . . . and pull!’ because they’d sidle up to you and take you by the arm and say, ‘You come! Chant, become happy’—and, really, they were very persuasive. And so, not surprisingly, a lot of people actually did what they asked and went absolutely cold to those early meetings. And that was their first experience with Buddhism.”

That was during the ’60s and ’70s, when SGI (then Nichiren Shoshu of America, or NSA) recruited anyone and everyone, without bothering to determine who was actually interested. On the surface this would seem to align NSA with some of the more better-publicized cults of the era, which employed similar strategies, but the philosophy undergirding NSA evangelism was quite different. As Buddhist scholar David Chappell writes in his essay “Racial Diversity in the Soka Gakkai”:

Not only did NSA recruit everyone, it believed in the value of everyone. NSA taught a view of Buddha-nature in each person, which functioned regardless of conditions. . . . This universal affirmation of the value of every human being is found in Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, but the way Soka Gakkai applied this principle to all strata of society without demanding a change in their lifestyle, was exceptional and represents a distinctive feature.

Indeed, perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of Nichiren Buddhism is that it does not require the suppression of human desire. Chappell reports the amazement of longtime SGI members who, as young hippies during the 1960s, had asked NSA leaders if they could chant for sex and drugs, only to be told that it was absolutely okay. It was understood that anyone, of any race, color, class, or predilection, could come to NSA just as they were. No one was excluded. And a monastic style renunciation was hardly required. Worldly needs, concerns, or attachments, far from being an impediment to joining, were actually the vehicle for transformation. For though one might very well begin by chanting for a car or more money, or even sex (and, according to NSA members, actually get it), through the transformative effects of daily practice that “small desire” would eventually give way to the “great desire” for the salvation of all beings. Daily practice was a process of introspection whereby one addressed more and more deeply the question “What really makes a human being happy and fulfilled?” And because it was a process, you could begin it right where you were. It was in many ways the most carefully conceived approach to Buddhist lay practice ever developed, in Asia or anywhere else.

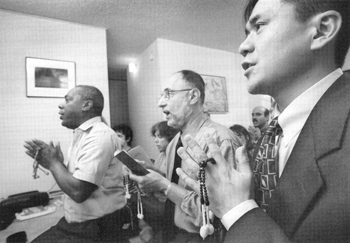

At Soka Gakkai meetings, then as now, members perform gongyo—the chanting of excerpts from the Lotus Sutra, followed by a prolonged session of nam-myoho-renge-kyo and a series of silent prayers. Afterward, there is typically a short presentation of some kind, usually highlighting an aspect of Nichiren’s teachings, or perhaps a reading from the writings of SGI President Daisaku Ikeda. Finally, members begin to share their experiences with one another, offering support and encouragement to the other members in their daily struggles, in much the same manner as the members of a Twelve Step group. Chappell observes:

Since a person is the cause of his/her karma, [that] person also has the power to change it. Those SGI members who give guidance remember that they cannot solve the problems of other members and do not try to do so. Instead they give practitioners encouragement to keep striving with their problems and to see their problems both as their karma and as a gift to bring about a practical benefit. The secret at the heart of Soka Gakkai is the discovery that, through practice, individuals participate in a universal reality that unleashes their personal creativity to transform life’s problems into blessings, to “change poison into medicine.” This is the fuel that feeds the life of Soka Gakkai.

Transforming poison into medicine is the heart of SGI practice, which consists of twice-daily gongyo chanting, a ritual reenactment of an event from the Lotus Sutra called “the Ceremony in the Air.” Like a number of other sutras, the Lotus Sutra takes place on Vulture Peak, a mountain near the ancient city of Rajgir, in northern India. But eleven chapters into the sutra, the scene shifts to the heavens above, as Shakyamuni, Maitreya, and the assembled bodhisattvas literally transcend the temporal plane, rising high into the air. Daisaku Ikeda writes, “The Lotus Sutra teaches a way of life in which we gaze serenely at reality from an elevated state of life—high in the air, as it were—and yet, at the same time, actively involve ourselves in those realities as reformers.” This is why at the conclusion of the Ceremony in the Air, Shakyamuni returns to Vulture Peak. Explains Ikeda, “We can change nothing unless our feet are firmly planted on the ground.”

The emphasis on reform in Nichiren Buddhism cannot be overstated, and for that reason it has been called by some scholars a “prophetic” form of Buddhism—one that is more committed to social realities than to mystical ones. But it would perhaps be more accurate to say that it is committed to “social realities as well as mystical ones,” or even “social realities as mystical ones,” for in the practice of Nichiren Buddhism there can be no separation between the two. SGI members in particular are taught to transform themselves through daily practice as a way of transforming their environment, with an emphasis on demonstrable results, and this, more than merely chanting for worldly benefits, is what has motivated so many African Americans and other minorities to join SGI. For it is the disenfranchised in a society who are most likely to seek to reform it, the disenfranchised as well who are most likely to understand that self-empowerment is the only effective plan. They cannot expect others to do the work for them—in many cases, those others aren’t even aware of the work that needs to be done.

Earlier this year, writing for Turning Wheel about the experiences of African American Buddhists, DePaul University’s Lori Pierce wrote:

I have seen white Buddhist practitioners evince utter shock that there might be a “race issue” [in their sanghas], because they themselves don’t feel like they have done anything wrong. They misperceive racism as intense bigotry—bad feelings between individuals or groups. Racism, as they understand it, is the Klan burning a cross on someone’s lawn in the middle of the night. They do not conceive of it as real-estate redlining, underfunded schools, and the disproportionate number of minorities in American jails. American popular culture perpetuates this simplistic notion of racism as simple bigotry, so it is difficult to help people unlearn it. And, because Americans wholeheartedly believe in the myth of hard work, individual effort, level playing fields, and color-blind opportunities, we have a hard time hearing or talking about power and privilege.

The fact that white Buddhists have so little awareness of what it feels like to shoulder the burden of America’s legacy of racism has no doubt contributed to the largely segregated cultures of most American meditation centers. As Charles Johnson, author of Turning the Wheel: Essays on Buddhism and Writing and a contributing editor to this magazine, explains: “If one is in the majority, unenlightened, and holds the reins of power in samsara—the world of racial dualism, egotism, and Them vs. Us—one naturally defines the world in one’s own (white) image.”

No wonder those forms of Buddhism with the strongest appeal to white Americans (Zen, Vipassana, Vajrayana) have won so few African American converts. The reasons sometimes advanced for this sound plausible enough: It is because meditative traditions, with their focus on monastic-style retreats, tend to require more disposable time and income than working-class minorities can afford. Or that the silence and rigidity of most Zen centers is temperamentally unappealing to African Americans, whose spiritual heritage is more rooted in the rousing rhythms of gospel music. Or even that these other traditions, so intellectually demanding, tend to appeal to those with advanced education. But none of these explanations bears up under scrutiny. Many of today’s African American SGI members have careers that afford them the time and money to attend a Zen retreat, if they want to. Likewise, with many thousands of Americans leaving their birth religions each year to embrace Buddhism, it seems disingenuous to suppose that it is a bigger leap to Vipassana from the African Baptist Church than it is from, say, orthodox Judaism or Catholicism. As for the intellectual requirement, there are formidable intellectuals among the Soka Gakkai, only it is perhaps fair to say that they have little patience for intellect without application.

No, the reason these meditative traditions have attracted so little diversity is ultimately far simpler. For all the Asian-Buddhist flavor of lighting incense, sitting on zafus, or chanting in Tibetan or Japanese, these traditions are in reality dominated by a white culture that is virtually invisible to its own members, who as representatives of the dominant culture have limited awareness of race issues and little real incentive for addressing them.

When African Americans step into a Buddhist meditation center, that invisible culture is the first thing they see. They may be strong enough to participate in it without losing heart, or their racial identity, or both. Or they may be so strongly motivated to practice in that particular tradition that it just doesn’t matter. In any event, they won’t be kicked out for being black, because there are few outright bigots in the white Buddhist world. But the deeper racism, the passive racism committed to all the mannered nuances of its own culture—that is felt right away. No wonder most African Americans never make it through the door. There’s no sign saying they can’t come in. There doesn’t have to be.

“Walk through the door of almost any SGI center in America, and you immediately notice there are many different kinds of people there,” American Buddhism scholar Richard Seager wrote to me in a recent email. Taking him at his word, I stopped by the New York Community Center on East Fifteenth Street one Tuesday shortly after noon. I had already read the literature of the organization and chatted with a handful of Buddhist scholars and sociologists on the subject, but I was still unprepared for the cultural disorientation I felt—the Buddhist cultural disorientation, that is. In terms of the people gathered there, it felt more like a subway or a New York City street corner than a Buddhist practice center.

Of the dozen or so Buddhists who had slipped into the fourth-floor shrine room to chant on their lunch break, I was one of only two Caucasians. The rest—a mixture of African American, Latino, Filipino, Asian, and one or two ethnic nationalities I couldn’t place—were all seated in folding chairs facing the gohonzon, a large scroll, originally inscribed by Nichiren, which is said to function as a mirror for one’s own Buddha-nature. No one remarked on my presence there, other than a friendly nod once or twice. If their presence in an American Buddhist context seemed anomalous to me, mine was scarcely worth noting from their point of view. They were used to the racial mix. In many cases that had probably contributed to their decision to join SGI.

Ronnie Smith remembers the first meeting he attended at the Washington, DC, Community Center in 1972: “I’d never experienced anything like it in my life, the sheer diversity in that room—Asian, African American, Caucasian. Just to observe the relationships between all those different people and to see how genuine they were and how they really seemed to respect one another—that was such a Buddhist education.” Patricia Elam, a writer and former attorney who joined SGI in 1987, had a similar experience. Growing up in Boston where, in the racially charged 1960s, she was one of the first African Americans to attend the all-white Windsor School, she recalls:

A lot of what I learned had to be undone when I became a Buddhist. In terms of the teachings, once you really begin to understand and believe that you are buddha and the buddha is inside you and there are buddhas all around you, then you have to readjust some of the thinking you’ve grown up with. It’s often said that Sunday is the most segregated day of the week, and it’s true: My friends, Christian and Jewish, where they worship everybody pretty much looks just like them. But not SGI. The core teachings of SGI ask you to embrace the idea that everyone has limitless potential. Women can be buddhas, criminals can be buddhas. Once you internalize that, then you have to proceed with the idea that racially and in every other way we are all the same.

This universalist position, which sees race as “fictitious,” is not without its critics. Lori Pierce notes that in Chappell’s 1997 study, one African American respondent identified her race as “human,” while another said, “I am not a black girl. With all my heart I am a person. . . . I am just me.” Pierce writes:

To counterpose blackness and humanness is to follow the racist logic that has plagued us for centuries. Certainly we need to rid ourselves of hate, but why are we required to rid ourselves of ethnicity in the process? This is only necessary if we believe, as white supremacy requires, that our racial selves are somehow a problem, a barrier to full self-realization.

But, as Elam points out in defense of SGI, “It’s not that we don’t embrace our racial or cultural differences—we do. It’s just that one race or culture is not better than another.”

SGI-USA has had its share of growing pains over the past forty-three years, including charges of racism within the organization—in most cases not bigotry, but racism in its more subtle, insidious guise. Ronnie Smith speaks of being passed over for a position as area leader even though he was a more qualified and experienced candidate than the white member who received the position. “I don’t think it was conscious at all,” he explains.

When we begin to practice, we bring in all our baggage with us; we don’t check it at the door. I think they just chose the person they were most comfortable with, the person who was most like them—who in that case happened to be white. When I first pointed this out, some people were shocked that racism could exist in an organization that was already so diverse. But it was obvious to me, so I had to take the responsibility for addressing it. Since then we’ve made extra efforts to recognize how valuable diversity is. As an organization we have wonderful ideals, but it’s not always easy to manifest them, so we make a conscious effort not to fall into the old habits of mind.

Today over twenty percent of SGI-USA leadership is African American, suggesting that, while old habits may die hard, they are nevertheless subject to correction when addressed in a conscientious manner. And far from requiring members to give up their racial identity, the organization actively celebrates those identities along the full racial spectrum of its membership. Since 1997, SGI-USA has sponsored countless cultural festivals and conducted more than twenty-five national conferences on race or language-related issues (including the historic Practicing Buddhism as People of African Descent Conference in 2002). Perhaps even more noteworthy, as David Chappell points out, is the fact that SGI is “the only Buddhist organization in America prepared for the emergence of Hispanic culture as a dominant feature of the United States in the twenty-first century.” SGI is currently the only Buddhist organization in America that (1) regularly holds local and national meetings in Spanish; (2) sponsors annual Latino festivals in New York, San Francisco, Chicago, and Los Angeles; and (3) publishes a regular Spanish-language newsletter. In fact, many of the new Hispanic members arriving for the first time at SGI community centers are already members of SGI, having been converted in South America, where SGI has branches in every country.

Arguably, an organization that has racial diversity has to learn to cope with racial diversity, and SGI has been a model Buddhist organization in this regard, offering inspiration to the culture at large (which is likewise diverse, but not yet fully coping) and to the predominantly white Buddhist culture of Zen, Vipassana, and Vajrayana (which could learn from SGI how better to cultivate what diversity it has, thereby coming into a fuller and more authentic engagement with American society).

But finally, there is little reason to feel ashamed of the monocultural atmosphere of most American Buddhist meditation centers. SGI has had an advantage from the beginning, there being a fairly significant difference between a form of Buddhism brought to this country by a white religious scholar (as Paul Carus brought D. T. Suzuki, and therefore Zen) and one brought over by the Japanese wives of U.S. servicemen—many of them African American. Racial diversity is in some sense the birthright of the Soka Gakkai because of its origins in the prophetic, socially engaged Buddhism of Nichiren, and ultimately because of the Lotus Sutra itself, which posits the fundamental equality of all beings. But that diversity was effectively “born in the USA,” not in Japan. For it was only here, in the ’60s and ’70s, that the egalitarian ideals of SGI and Daisaku Ikeda encountered for the first time a racially diverse culture where those ideals could be put to the test. It was a culture ready to embrace a newer, more modern, and decidedly global religious ideal, and Soka Gakkai International fit that profile to perfection. It was the expression of a bodhisattvalike social vision deeply rooted in the American experience but seldom realized in actual practice: equality and justice for all.

In the middle of the Ceremony in the Air, at the beginning of a chapter of the Lotus Sutra entitled “Emerging from the Earth,” Maitreya and the other bodhisattvas are so moved by the Buddha’s discourse on “Peaceful Practices” that they spontaneously offer to protect and uphold that sutra after Shakyamuni’s passing away. Unexpectedly, Shakyamuni declines. There is no need, he explains. Already there are innumerable bodhisattvas residing in the space beneath the earth whose task it is to protect and widely proclaim this sutra. Indeed, at that instant the earth trembles and splits open, and those “new” bodhisattvas emerge.

At that time the bodhisattva and mahasattva Maitreya, as well as the countless other bodhisattvas, found doubts and perplexities arising in their minds. They were puzzled at this thing that had never happened before and thought to themselves: How could the World-Honored One in such a short span of time have converted an immeasurable, boundless asamkhya [innumerable quantities] of great bodhisattvas of this sort?

Some forty-odd years after the first appearance of Soka Gakkai in America, the same question might apply. Only in this case the answer is less difficult to discern.

Ronnie Smith tells the story of coming to the Washington Community Center when he was nineteen, searching for happiness but still strung out on drugs: “In the beginning there was a man named Ted Osaki. He was the local leader here at the Washington headquarters, and his compassion for the members was really remarkable. He had this ability to inspire us young people in particular about how important our lives were and how much power we had to change society and create world peace.

“He would tell us about how in the Lotus Sutra the question was asked at the Ceremony in the Air about who would bring world peace, and all the monks thought it would be them. But then the Buddha said no. It would not be the monks but ‘the Bodhisattvas of the Earth,’ not the intellectuals who were well versed in all the Buddha’s teachings but the common man, the common mortal. He told us that we were the Bodhisattvas of the Earth and that we would create world peace through our efforts and our practice.

“He would cry as he said this. And I would cry, too.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.