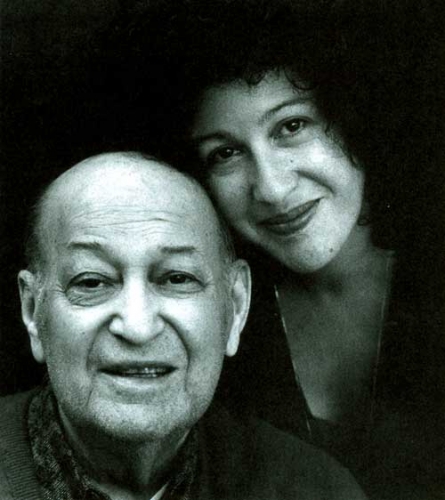

At one point when I was sitting with my father, I said, “Dad, are you afraid of dying?” And he said, “I was, but not now.” He didn’t speak of death a lot. There wasn’t a lot to say, really, it was so in your face, so obvious. And he wanted to live up until the moment of death. He didn’t dwell on the fact that he was dying and he didn’t deny it.

I remember giving my father a little teaching that said, “Death is like taking off a tight shoe.” I put it on a piece of paper for him and gave it to him. He kept that by his bed.

I didn’t have any formal practices that I shared with my father. When I was in the room with him, that was the practice. It felt to me that doing anything else was taking me away from the moment. Looking into my father’s eyes was the practice, touching his head, changing his diapers. Just being with him was my practice. There were times, many times, when I lost it. When I couldn’t be mindful, when I couldn’t see my true nature at all. And I was just a daughter mourning her father.

It was six months before he died when hospice came into the home, and I began coming more frequently. Each time I came it would be a shock, because I wasn’t able to see the gradual changes. At some point he needed a wheelchair, and all along the way his body was changing.

The hospice people would come in the morning and wash him. By then he was incontinent—he couldn’t get up to use the toilet. One time my father called me into his room and said he needed my help to use the urinal. I saw my father’s genitals for the first time as I cleaned him up and put back the diaper. I felt really awkward. But he looked at me and he said, “What’s the matter? Haven’t you ever seen a pisher before?” Which was very typical of him. And I said, “Well, yeah, but not yours.” It was a great moment between us. There was an unspoken acknowledgment of the situation.

Another time, my mother had left the house and my father called out for me. We had a commode by the bed which he really had trouble with. I said, “Can I help you with the commode?” He said, “No. I’m going to the toilet.” It was his last visit to the bathroom, and he was going to do it himself. I picked him up, and I don’t think his feet were touching the floor. I thought I was going to drop him. I was all alone with him. I helped him sit down and then I left the bathroom. When he was ready he flushed the toilet and I helped him back to bed. Then I had to clean him. It was transformative: seeing impermanence right there before my eyes and seeing my own ability to ease his suffering no matter what it took. I dried him off and I tucked him in. He looked up at me and he said quietly, “You did okay. You did okay.”

I couldn’t imagine bearing my father’s dying without my practice. I am certain that my practice and study over years greatly influenced my ability to be present in the midst of my father’s suffering. Sitting for hours with back pain, or amidst tears or fear or boredom—all those years of practice really came to my aid when I needed it most. I didn’t have to run when fear came up, or a great deal of grief or pain. In some way I had no choice when my father called out for me, but perhaps I could have fallen apart, or collapsed, or called out for someone else. It gave me courage to feel open to things as they are, which is so much a part of the teachings.

I would practice mindfulness when I was in the room with my father, being present to everything that was happening: the smells, the sounds, the feel of his skin, his hair. And there were times when I was able to step back and ask, “Who or what is experiencing this?” I was able to inquire into the nature of what was happening—to do more than just sit there and take it at face value. And this inquiry would often happen when I was experiencing strong emotions. There were times when I could actually not drown in these emotions but inquire into who or what was feeling them. At other times, I was utterly attached.

I said to one of my teachers about a year after my father’s death, “Shouldn’t I not feel as attached by now?” And he said, “It is your very ability to feel such deep attachment and emotion that leads you to be able to cultivate compassion for others.” This was wonderful to hear, because I was thinking, I’m not much of a practitioner after all. He helped me to see that I was still attached and somehow able to see beyond that at the same time.

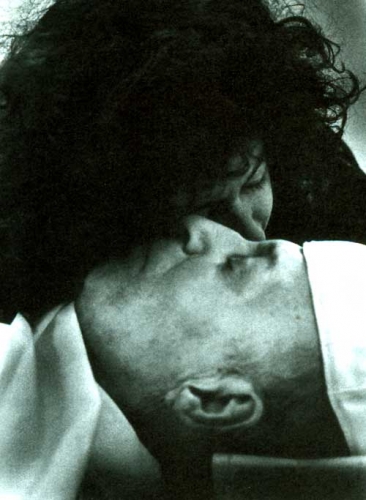

The last time I saw my dad alive, I walked into his room to say good-bye. He had gone very far away. And I put my cheek next to his and I said, “I’m going to miss you.” I had a very clear sense of him going. “I’m going to miss you, Dad.” He was so weak he couldn’t hug me, but he put his hand on me and said, “I know. I’ll miss you too.” And those were our last words.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.