Whenever I’m asked if the dharma makes possible social transformations that are relevant for the specific and seemingly endless problems of the world today (and I’m asked this often), I find myself considering that question in light of a provocative critique presented forty-five years ago by Paul Tillich, the great Christian theologian, who called Buddhism “one of the greatest, strangest, and at the same time most competitive of the religions proper.” In 1963, Tillich published Christianity and the Encounter of World Religions, a series of lectures he gave one year after his return from a nine-week lecture tour in Japan in 1960. In the book’s third chapter, “A Christian-Buddhist Conversation,” Tillich takes up the social and ethical consequences, as he sees them, of his religion in contrast to the Buddha-dharma. Regarding his faith, he states that a Christian’s dedication to the passages in the New Testament that describe agape—an unconditional love for others—translates into an energetic form of the social gospel that emphasizes “the will to transform individual as well as social structures.”

“The Kingdom of God has a revolutionary character,” wrote Tillich. “Christianity . . . shows a revolutionary force directed toward a radical transformation of society. . . . Most of the revolutionary movements in the West—liberalism, democracy, and socialism—are dependent on it, whether they know it or not. There is no analogy to this in Buddhism. Not transformation of reality but salvation from reality is the basic attitude. . . . No belief in the new in history, no impulse for transforming society, can be derived from the principle of Nirvana.”

Tillich quickly concedes that a conquering, self-confident will may be problematic because it “leads to the attitude of technical control of nature which dominates the Western world.” But for Tillich, while Buddhism’s version of agape—metta, or lovingkindness toward all sentient beings—can lead to identification with the Other, and thus to empathy, nevertheless “something is lacking: the will to transform the other one either directly or indirectly by transforming the sociological and psychological structures by which he is conditioned.”

It is here that the dialogue between Buddhists and Christians (and possibly some social activists) reaches a “preliminary end” for Tillich. At the end of the chapter, Tillich imagines this exchange between a Buddhist priest and a Christian philosopher:

The Buddhist priest asks the Christian philosopher: “Do you believe that every person has a substance of his own which gives him true individuality?” The Christian answers, “Certainly!” The Buddhist priest asks, “Do you believe that community between individuals is possible?” The Christian answers affirmatively. Then the Buddhist says, “Your two answers are incompatible; if every person has a substance, no community is possible.” To which the Christian replies, “Only if each person has a substance of his own is community possible, for community presupposes separation. You, Buddhist friend, have identity, but not community.”

The distinguished Zen teacher and scholar Masao Abe praised Tillich for being “the first great Christian theologian in history who tried to carry out a serious confrontation between Christianity and Buddhism in their depths.” His influence on spirituality in America has been wide and deep; among those he inspired was Martin Luther King, Jr., who based his goal of achieving the “beloved community” on the concept of agape and devoted his dissertation at Boston University to Tillich (“A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman”).

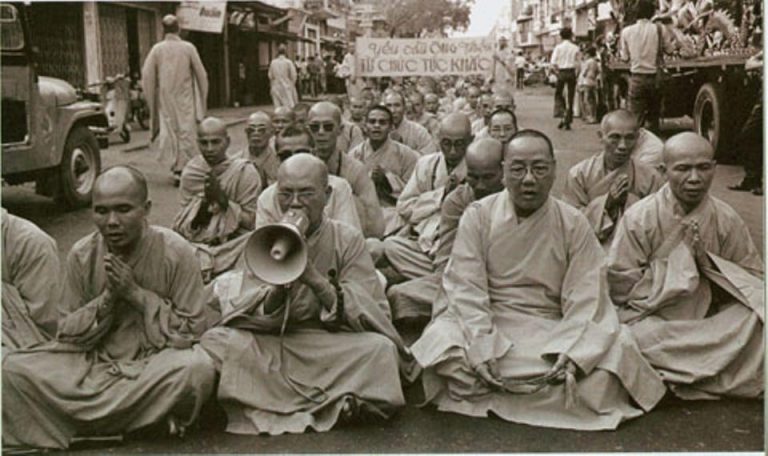

To my eyes, Tillich’s assessment of the social and political shortcomings of Buddhism leaves a good deal to be desired, especially since it does not account for the “engaged Buddhism” that emerged in the 1960s. Nevertheless, his sincere misgivings are shared by many non-Buddhists, as well as by some new members of the American convert community as they struggle to integrate their practice into a contemporary need for political activism, which for over two millennia was judiciously separated from the Buddha-dharma by traditional Buddhist monastics. As students of the dharma, we should be able to clarify Tillich’s questions – the relationship between Buddhist practice and our political commitments, and how anatta (no-self) fits with a sense of community. This begins with mindfulness of how key historical figures and principles of Buddhism anticipate and resolve the question “Is a will toward social transformation lacking in traditional Buddhism?”

For one answer, we need only look to the remarkable life and works of Ashoka, ruler of the Maurya kingdom from about 272–236 B.C.E. After waging but one military campaign, which conquered the Kalingas around 264 B.C.E (150,000 were deported, 100,000 were killed, and many more died), Ashoka was so appalled by the carnage and cruelty of war that he embraced the dharma and for twenty-eight years devoted himself to the creation of hospitals, charities, public gardens, education for women, the protection of animals, and caring for everyone in his kingdom. He exercised compassion toward lawbreakers and prisoners, cultivated harmonious relations with neighboring states, and encouraged the study of other religions.

The wise lay Buddhist Ashoka was hardly alone among leaders who translated the virtue of ahimsa (nonharm) into civic life. In his book Inner Revolution, Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman reminds us that the revered second-century monk Nagarjuna [see “The Second Buddha.”] was the mentor of the South Indian King Udayi; he told him, “O King! Just as you love to consider what to do to help yourself, so should you love to consider what to do to help others!”

According to Thurman, Nagarjuna, whose counsel is recorded in the five hundred verses of The Precious Garland, “taught his friend the king how to care for every being in the kingdom: by building schools everywhere and endowing honest, kind, and brilliant teachers; by providing for all his subjects’ needs, opening free restaurants and inns for travelers; by tempering justice with mercy, sending barbers, doctors, and teachers to the prisons to serve the inmates; by thinking of each prisoner as his own wayward child, to be corrected in order to return to free society and use his or her precious human life to attain enlightenment.” Thurman observes: “This activism is implicit in the earliest teachings of the Buddha, and in his actions, though his focus at that time was on individual transformation, the prerequisite of social transformation.”

Buddhist history, with which Tillich may not have been well acquainted, offers us time and again concrete examples of how the dharma has inspired enlightened social policies. But, like many Western intellectuals, Tillich was unable—or perhaps unwilling—to accept the doctrine of anatta, and worried a bit more than he should have about defining nirvana. Yet we cannot dismiss too quickly the pivotal questions he raised: Without a belief in true individuality, a discrete ego that is enduring, immutable, and independent from other essences, can there be a community of individuals in the dharma? Is there truly no will to transform the lives of others in Buddhism, but only the intention to secure one’s own salvation from reality?

Clearly, asking these questions from the standpoint of nirvana is as nonsensical as asking “What is the distance from one o’clock to London Bridge?” Ultimate truth (paramartha-satya) is a nonconceptual and nondiscursive insight into ourselves and the world. Nirvana literally means “blowing out” (Sanskrit nir “out,” vana “blown”) craving and a chimerical sense of the self, like a candle’s flame, allowing us to experience things in their true impermanence, codependency, and emptiness (shunyata). “In Buddhism,” Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us, “we never talk about Nirvana, because Nirvana means the extinction of all notions, concepts, and speech.”

However, Buddhism also acknowledges a region of conventional, relative truth (samvriti-satya) that is our daily, lived experience, and for this reason Shakyamuni Buddha in the sutras can refer to his disciples individually and by name. Here, in the realm of relative truth and contingency, of conditioned arising, each person presents to us a phenomenal, historical “substance,” which due to custom and habit we refer to as “individuality.” The same things have not happened to or shaped us all since birth. Our lives differ so radically and with such richness that, personally, I prefer to see the Other as a great and glorious mystery about which I can never make any ironclad assumptions or judgments. The very act of predication is always risky, based as it is on partial information that is subject to change when new evidence arises.

Thus, what is required of us in the social world is nothing less than vigilant mindfulness. Even though we can say that each person has a “separate” history, the dharma teaches—as does quantum mechanics—that we are really a process, not a product: We are each an “individuality” ever arising and passing away, every one of us a “network of mutuality,” as Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said. In the ontology of the Buddha-dharma, everything is a shifting assemblage of five skandhas, the “aggregates” that make up individual experience, with no “essence” or “substance” discernible in the concatenation of causes and conditions that create our being instant by instant. For this reason, if I am practicing mindfulness, phenomena ever radiate a surprising and refreshing newness. The “cold” and “wetness” of the water I drank at noon can never be the same “cold” and “wetness” of the water I drink at night. My wife of thirty-six years is hardly—as she will quickly tell you—the same young woman I wooed when we were both twenty years old. (Nor am I the same naive young swain I was back then, thank heaven!) Far from being “salvation from reality,” as Tillich stated, Buddhist meditation is instead a paying of extraordinarily close attention to every nuance of our experience.

Something I find worthy of contemplation is how in the dialectic between samsara and nirvana, the dreamworld of samsara is logically prior to and quite necessary for the awakening to nirvana. Discussing Tantric Buddhism, scholar Gunapala Dharmasiri says, “We make a Samsara out of Nirvana through our conceptual projections. Tantrics maintain that the world is there for two purposes. One is to help us to attain enlightenment. As the world is, in fact, Nirvana, the means of the world can be utilized to realize Nirvana, when used in the correct way.”

Perhaps a more concrete way of expressing this in terms of social action is to say we come to the Buddha-dharma precisely because the suffering we have experienced in the world of relativity forces us to relentlessly question “conventional” truth and the status quo, as Ashoka discovered after his slaughter of the Kalingas brought him no happiness, or as the Buddhist monk Claude AnShin Thomas realized after killing civilians during the Vietnam War. Or we can consider the case of a black American born in the late 1940s, as I was, a person who knows firsthand the reality of racial segregation in the South and North fifty years ago, and the subtler forms of discrimination in the post-Civil Rights period, which I call Jim Crow-lite. He (or she) discovers that many Eurocentric whites project fictitious racial “substance” (or meaning) onto people of color, never seeing the mutable individual before them—just as unenlightened men do with women. They dualistically carve the world up in terms of the illusory constructs of “whiteness” and “blackness” and, on the basis of this mental projection, create social structures—as Tillich declared—that fuel attachment, clinging, prejudice, and what the dharma describes as the “three poisons” of ignorance, hatred, and greed. A black poet expressed powerfully his pain at this reality when he wrote, “Must I shoot the white man dead/To kill the nigger in his head?”

Fortunately, a black American who has been exposed to the Buddha-dharma sees that these racial illusions, so much a part of conventional reality—just as the caste system was in the time of the Buddha—are products of the relative, conditioned mind. He realizes that while he is not blind to what his own valuable yet adventitious racial, gender, or class differences reveal to him, neither is he bound by them; and those very phenomenal conditions may, in fact, spark his dedication to social transformations intended to help all sentient beings achieve liberation. The Buddha employed upaya kaushalya (skillful means) when he taught the truth of anatta, and said he would teach a doctrine of self if his followers became attached to the idea of no-self. Always, his teachings bring to the foreground the importance of a radical freedom.

As the first line of the Dhammapada says, “All that we are is the result of what we have thought.” Thus, the transformation of sociological and psychological structures must take place initially in our own minds—and those of others—if we truly hope to address the root cause of social suffering. The Four Noble Truths, the five precepts observed by laity and monks alike, the Eightfold Path, and the ten paramitas (perfections) make up a time-honored blueprint for revolutionary change, first in the individual, then in the community of which he or she is a part.

We must, I believe, agree with Tillich when he proclaims that Buddhism is one of the “most competitive religions proper.” Without reliance on a higher power, it is competitive exactly to the degree that it is noncompetitive and nondualistic, an orientation toward life that avoids the divisions and divisiveness that are the primary causes of our social problems. This rare quality, together with an answer for how relative individuality can be reconciled with our nirvanic “original face,” is beautifully present in a biographical detail from the life of Hui-neng, the sixth patriarch of Zen. When he presented himself to the abbot of Tung-shan monastery in the Huang-mei district of Ch’i-chou in hopes of study, Hui-neng portrayed himself as a poor “commoner from Hsin-chou of Kwangtung.”

The abbot rebuked him: “You are a native of Kwangtung, a barbarian? How can you expect to be a Buddha?”

“Although there are northern men and southern men, north and south make no difference to their Buddha-nature,” replied Hui-neng. “A barbarian is different from Your Holiness physically, but there is no difference in our Buddha-nature.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.