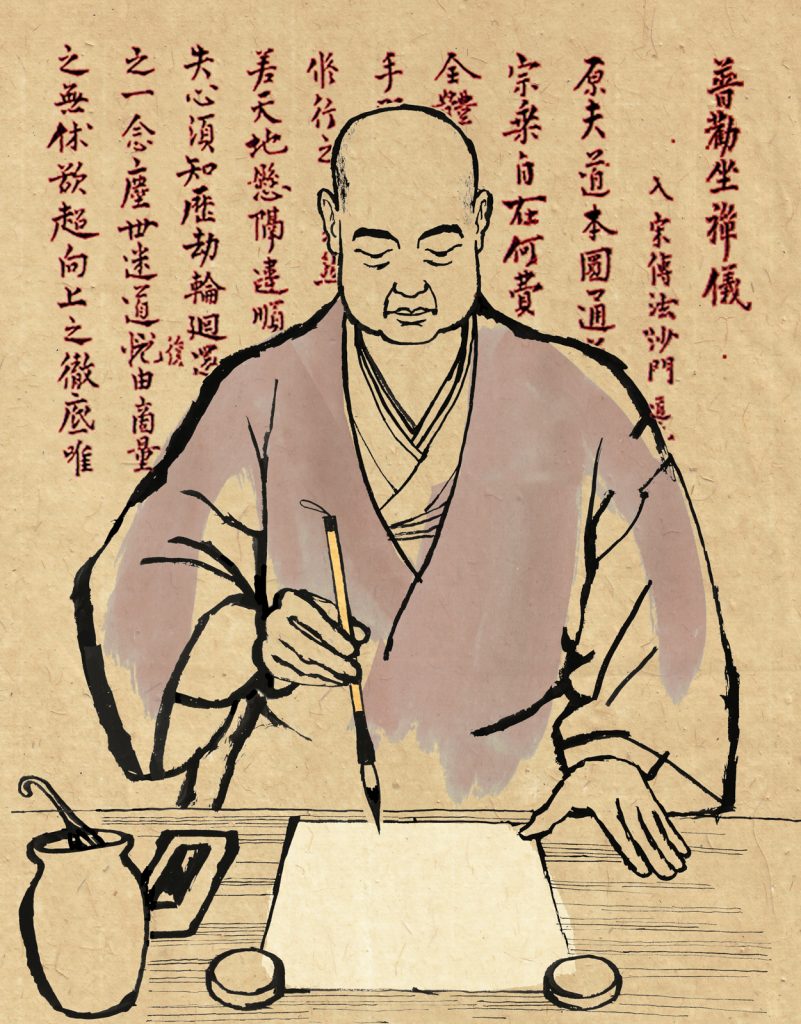

Eihei Dogen is considered one of the great masters in the history of Japanese Buddhism. He was a reformer of Buddhist monastic practice and the founder of the first independent Soto Zen monastery in Japan. He was not only the leader of a Zen community but also a wonderful writer whose collection of writings entitled The True Dharma-Eye Treasury (Jpn., Shobogenzo) is cherished by Buddhists, religious scholars, philosophers, and lovers of literature around the world.

What is less known, however, is Dogen’s affinity for poetry. Dogen was born into the Minamoto family descended from Emperor Murakami, and his father held the position of chief councillor in the emperor’s court. He received the best education available, intended to train an aristocrat to become a high-ranking court officer of the imperial government. For such a position, one needed to be not only a capable politician but also a scholar and poet. Dogen’s father was an excellent waka poet (waka literally means “Japanese poetry,” as opposed to kanshi, which are Chinese poems) and one of the editors responsible for creating the New Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern. This is one of the eight anthologies of waka created at the imperial court and is considered to be one of the three most influential.

Dogen himself composed more than four hundred Chinese poems included in Dogen’s Extensive Recozrd (Eihei koroku), as well as some Japanese waka poems. Waka were considered a less important method of expressing insight than kanshi. In Japanese Buddhist communities Chinese was the primary language for formal writing, as Latin was for Western Christians. When he gave formal dharma hall discourses, Dogen usually included Chinese poems. Upon request, however, he also composed waka as aids in teaching the dharma.

It is well known among scholars and practitioners that Dogen disparaged the value of literature. In the collection of talks entitled Shobogenzo Zuimonki (not to be confused with the aforementioned Shobogenzo), he wrote:

Zen monks these days are fond of studying literature as a grounding to compose verses or write dharma words. This is wrong. Even if you cannot compose verses, just write what you think in your mind. Even if your style is not sophisticated, write down the dharma gates [methods of practice]. People without the mind of awakening will not read it if your writing style is not well polished, but even if the style is embellished and there are excellent phrases in it, such people would only play with the words without grasping the principle [behind them]. I have been fond of studying [literature] since my childhood, and even now I have a tendency to contemplate the beauty in the words of non-Buddhist texts. Sometimes I even refer to the Selections of Refined Literature or other classic texts. Still, I think it is meaningless, and it should cease immediately.

Some think, based on these remarks, that Dogen contradicted himself by writing so many poems. But Dogen was a complex person. In his poems, Dogen expressed his understanding without much consideration of sophisticated wording or rhetorical techniques. If he had wanted to, he presumably could have written highly embellished poems, as people did at the emperor’s court where he originally came from, but the waka poems attributed to Dogen are simple and without much ornamentation. Indeed, in this passage Dogen does not say that one should not write poems but indicates rather that poems should not be evaluated by worldly standards such as literary devices and flowery styles.

In the late 20th century, Dogen’s waka gained more popularity among Japanese intellectuals. Some of them have said that Dogen’s writing negated literature but in doing so opened a new horizon in the world of Japanese literature.

From my perspective as a Buddhist practitioner, these discussions among modern writers regarding the value of literature seem like idle talk. From the time of Shakyamuni, Buddhist masters have questioned the ability of language to express reality beyond discrimination and conceptualization, and yet the same masters all tried to express this reality using language, including Dogen. As he discussed in the Shobogenzo, Dogen never dismissed the importance of expressing reality, with or without language.

The following poems are selected from my translations of Dogen’s waka and include a short commentary. I have occasionally given dharma talks on these waka and have found that talking about the poems is a useful and focused way to study Dogen and become familiar with the teachings underlying them.

POEM ON THE OCCASION OF OVER A FOOT OF SNOW FALLING ON THE TWENTY-FIFTH DAY OF THE NINTH MONTH OF THE SECOND YEAR OF THE KANGEN ERA

In the month of long nights

it snowed on the bright leaves

Why don’t those who see this

compose a poem?

In 1243 Dogen and his sangha moved from Kyoto to Echizen province. The new monastery, Daibutsu-ji—later called Eihei-ji—was built in 1244. The opening ceremony for the dharma hall took place on the first day of the ninth month. This poem was composed at the end of that month. The monks’ hall was completed shortly thereafter, and the sangha moved into the new temple.

The waka begins with the Japanese phrase naga-tsuki, the shortened form of yonaga-tsuki, which means the month of lengthening nights, the ninth lunar month (which can begin anywhere from the end of September to the first weeks of October). In Kyoto, this is normally a mild season of changing leaves; snow is rare. Yet in the Hokuriku region, where Eihei-ji was built facing the Sea of Japan, winds from Siberia encountering the mountains rise and may force clouds to release their moisture as snow. Dogen, surprised by what he surely took to be an extraordinary phenomenon, used the image as a metaphor for the dharma. The whiteness of snow represents oneness, while the bright colors of the leaves manifest multiplicity. Each tree has its unique nature, shape, height, flower, fruit, and leaf color. Oneness and multiplicity live together. How can we express this interpenetration of absolute reality (oneness and equality) with conventional reality (multiplicity and diversity)? This is one of the essential points of dharma practice. How can we perceive and express the oneness of everything within the myriad things we encounter?

A POEM ON THE SEPARATE TRANSMISSION OUTSIDE THE TEACHINGS, WRITTEN ON THE OCCASION OF LORD SAIMYOJI’S WIFE REQUESTING A DHARMA VERSE WHILE STAYING ON THE OUTSKIRTS OF KAMAKURA IN THE YEAR OF THE FIRE SHEEP IN THE HOJI ERA

Precisely because the dharma

can be inscribed

only at the top of tall rocks

even waves cannot reach

along the rugged shore

Dogen visited Kamakura for about six months, from the eighth month of 1247 to the third month of the following year. Lord Saimyoji was Hojo Tokiyori, the regent of the Kamakura shogunate government at the time.

The Japanese word translated here as “inscribed” (kaki) means “to write” but also “oyster.” The word rendered as “dharma” (nori) can also mean the seaweed used in making sushi rolls. Dogen uses kaki and nori here as puns to create a double image of Kamakura’s coast and the nature of dharma: a rugged shore where oysters cling to tall rocks and the dharma can be inscribed only beyond reach of the waves of habitual discriminating thought.

“Separate transmission outside the teachings” is a famous phrase used for distinguishing the Zen tradition from the so-called teaching schools. Zen practitioners insisted that the Buddha’s heart, the absolute dharma that cannot be described in words, had been transmitted to them. Dogen criticized this idea in his fascicle of the Shobogenzo titled “Buddha’s Teachings.” He wrote: “do not believe the mistaken theory of ‘a separate transmission outside the teachings,’ and do not misunderstand what the Buddha’s teachings are.”

In this waka, Dogen says the dharma can be inscribed only at the top of tall rocks beyond the reach of discriminating thought—an observation that is different from the common usage of the phrase “separate transmission outside the teachings” to declare Zen superior to the written teachings on which other schools are based. But this waka seems to express only the first half of a statement; to complete it, we might add something like the following: “We should study the written teachings and practice them in our actual lives, which are beyond thinking.”

♦

Adapted from Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki: The New Annotated Translation—Also Including Dogen’s Waka Poetry with Commentary by Shōhaku Okumura ©2022. Reprinted by permission of Wisdom Publications

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.