We used to say that the first three-year retreat was like being put through the washer—heavy-soil program—and the second was like being hung out to dry. Scrubbing out the stains using Vajrayana enzymes; billowing and bleaching under the equanimous sun of blessing.

Most of the people I know who have spent time in retreat agree: in the beginning, you don’t really know what you’re getting yourself into. You underestimate how much of the “work” has to do with relating to your shadows alone in your practice space and in relationships with your fellow retreatants. You also tend to underestimate the tenacity of those stains, deep-rooted emotional issues, and subjective misconceptions.

By the time you get to second retreat, you know what to expect, and you may even look forward to the challenge. You trust the retreat master to bring your shadows to light, you air them out, let the sun whiten them . . . and then you look more deeply and there’s yet another shadow, yet another stain you thought had been scrubbed out once and for all. It seems endless.

It’s probably when you’re willing to let go of all of your hopes and fears around accomplishing anything, being anyone, attaining any level that the practice can really work its magic. And that, perhaps, is the next phase of practice: sprinkled with lavender water, gently ironed, folded, and ready for whatever use is required.

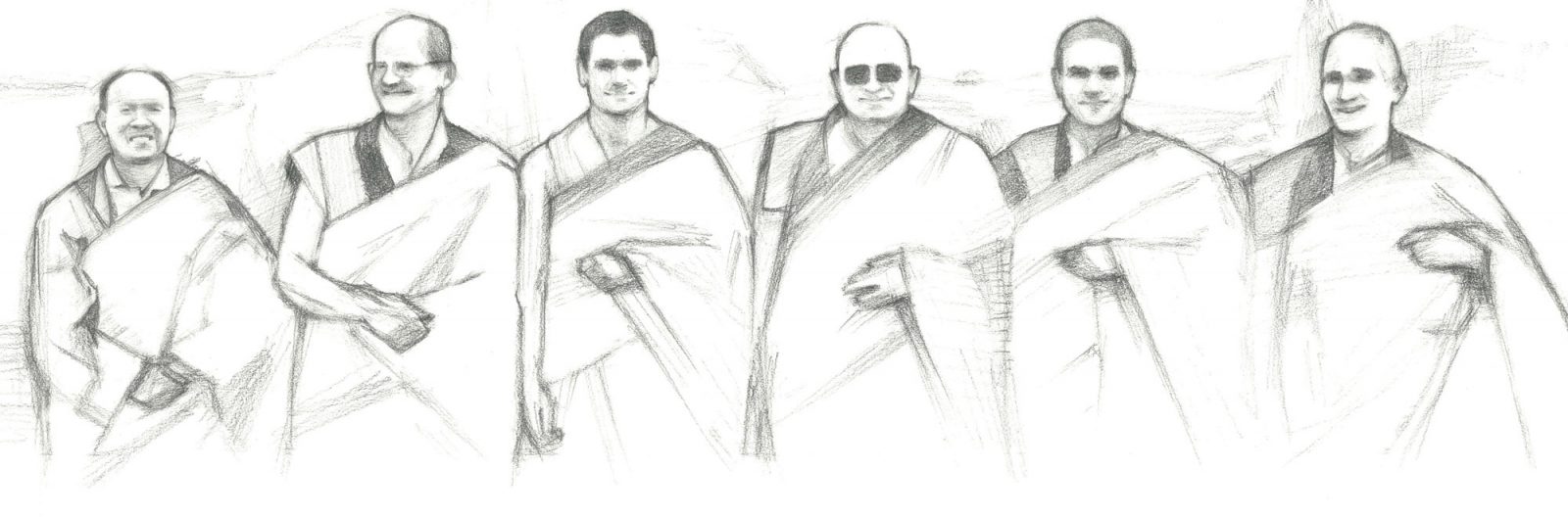

In August 2012, I met with the six fellows in the following roundtable just a few days before they reentered retreat. The atmosphere was joyful and energized. All had previously completed at least two traditional three-year retreats here in Dhagpo Kundreul Ling, the Karma Kagyu center in Auvergne, France, where I also spent six years in the 1990s (though I somehow got stuck in the rinse and spin cycles), under the guidance of the Tibetan master Gendun Rinpoche. Though Rinpoche passed away in 1997, his laughter, love, and inspiration are still very present.

Stephen Tenpa, the eldest, is practicing in his room in the monastery; the other five are together in the center where our conversation took place. A recent letter from Carlo Trinle Dorje tells me that they call themselves the “dream team” and are doing very well indeed.

–Pamela Gayle White, Contributing Editor

Could you tell us a little about yourselves?

Carlo Trinle Dorje: I was born in Brussels, Belgium, in 1959. I was a sports coach, then a life coach using therapeutic relaxation methods. I used to practice Zen; I taught meditation at the Kwan Um School and cofounded the Brussels Zen Center. This is my third retreat after several years in the monastery.

Iosif Lodrö: I was born in Athens, Greece, in 1962; I used to be a survey engineer. In 1990 I met Gendun Rinpoche, and he inspired me to stop working and begin preparing for retreat. We had to interrupt our first retreat in Greece due to difficulties with the Greek Orthodox Church, but then I came here and did retreat from 2001 to 2008 with Trinle.

Thomas Rabjam: I was born in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1955; I was a shipping logistics manager. I met Gendun Rinpoche in 1985 and began my first retreat in March 1991. After two group retreats, Rinpoche gave me permission to enter long-term retreat here, but after six years I fell ill and had to leave. I stayed in the monastery for exactly eight years, and now I’m going back in with these guys.

Viktor Jigme: I was born in 1977 in a small village in Kazakhstan near the Russian border; we moved to Germany when I was 15. I finished school, learned carpentry, and discovered the dharma sort of by accident when a friend took me to the center in Jägerndorf, where I lived for almost two and a half years before coming here. I entered my first retreat in 2001 with Trinle and Lodrö, and I’ve been doing three-year retreats ever since.

CTD: Jigme is going into his fourth retreat; he’ll be assisting the retreat guide.

Liem Kunga: I was born in Saigon, Vietnam, in 1950 and came to France to study management on a scholarship when I was 22. I stayed in Paris for 15 years, working as an administrative supervisor. I married there and had two sons.

In 1975 I met [Zen master] Taisen Deshimaru and belonged to his circle of close students until he died in 1982. After spending some time in Japan, I met Gendun Rinpoche and began retreat here in 1991. After two retreats I oversaw the congregation finances for some years, then moved to an affiliated center near the Riviera. When I came back to the monastery a few months ago I learned that there was going to be a retreat for “old warhorses,” and here I am!

Okay! And you?

Stephen Tenpa: Well, I don’t know . . . [Laughs.] I was born in Oklahoma in the ’40s. As a teenager I read books on Eastern philosophy; I liked the dharma. Around 1968, I formed an informal dharma group with some friends at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee who were also interested in Buddhism.

I moved to Spain in ’77 to teach English and took refuge in Barcelona. I’d decided that Tibetan Buddhism was more or less the path for me because it combined elements that I liked from all the other schools. In Barcelona they said there was this lama called Karmapa who was coming to France, so I went, and the 16th Karmapa was there along with many, many other high lamas. That’s when I met Lama Gendun and realized that he was exactly the teacher I’d been looking for.

For several years I spent my summer holidays in Lama Gendun’s center in Dordogne. One day he said, “We’re starting a three-year retreat in Auvergne, will you join?” I said I’d like to prepare much more, but he said, “No, it’s now or never.”

Why would anyone do a three-year retreat?

TR: As far as I remember, Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thayé established this retreat structure because during these three years the worldly prana [subtle energy] changes and can be purified through practice, giving you the chance to get closer to enlightenment. Your deepest habits can really change in three years.

IL: It’s a traditional way to go further on the path of dharma. It starts with basic practices and progressively moves on to more advanced practices, combining the two main streams of the Karma Kagyu lineage, Mahamudra and the six yogas.

Is it a common thing for Tibetan Buddhists to do?

VJ: No, it’s quite particular. You need a ground of knowledge beforehand or at least a very strong connection to this kind of practice, because it’s very formal and traditional; it isn’t everybody’s cup of tea, especially not 12 hours a day.

Most people in the world, including Buddhists, would find this a pretty radical move. What are the motivating factors?

TR: Each person is different. When I was in my late twenties I had already been working for 10 or 12 years. I was thinking, Do I want to be working every day? Do I really want to have a family and build a house like my father did? Is this my goal? And I understood that it wasn’t what I really wanted.

I’d met Gendun Rinpoche a few years before; he was such a splendid example of an enlightened master. He had a very special gift when he transmitted the dharma, including basics like impermanence, the causes of liberation, and so on. I was really attracted and decided okay, you should do one retreat, at least one, and then see what happens.

I think you need to make an honest decision, to ask yourself if you’re willing to give up your worldly life. It is a radical move, and you have to be firmly convinced that it’s the path for you; otherwise you’re always going to be wondering whether you’re doing the right thing or not.

IL: I think there must be the feeling that there really is something more to life. We all felt that something was missing: even though everything seemed fine, inside we were still asking questions.

What else?

IL: Along with personality, I think there are two other key factors. One is an understanding of the teachings on impermanence, samsara, suffering, and so on. The other is the inspiration of the lama. I find that devotion is very important and very simple: after a while you naturally try to follow the example and path of the lama as best you can.

VJ: Even though I never met Gendun Rinpoche, the teachers I saw in Germany who were his disciples really had his energy; they had it in the heart. They were far from perfect, they were human, but they had this other side that I found very inspiring. I thought, “If the three-year retreat takes you there, I want to do one.”

You guys already did at least two three-year retreats. And you’re going back. So something’s still missing?

ST: Enlightenment.

In the United States particularly, there’s the idea that the real way to practice is in the street, in relationships, and so on. Some people would say, “Well, aren’t you just escaping the reality of the world by going into retreat?”

IL: It’s true that it might seem like an escape, but in order to do this practice one must at least try to have the proper motivation: the deep wish to benefit all beings. I was outside for three years, and on a certain level I felt I could help others, but there were limits. I think if we really want to cultivate qualities so that eventually we can be of true benefit, like our masters, then it isn’t an escape. But the motivation has to be sincere.

CTD: People have told me that my choices inspire them to take another direction, to practice more. And I see that the closer I get to entering retreat, the closer I am to myself, and the closer I am to myself, the closer I am to others, because we’re not separated in mind or in heart. The connection may be invisible, but it’s very strong.

LK: I’m retired, my children are grown up, my parents are dead, and I don’t really have a girlfriend. At my age it is easier. It’s a more practical way to practice.

How did you decide to do another retreat?

CTD: After the last retreat Lodrö came back to visit, and we told him: “Lodrö, leave Greece and come spend more time with us in the monastery.” We were together in my room—Lodrö, Jigme, and me—and there was a big silence and a feeling of deep blessing, as if we wanted to cry, and finally we said, “Wouldn’t it be great to go back into retreat together!”

TR: The next day Trinle Dorje came to see me and said, “Hey, Rabjam, come with us, we’re doing another retreat.” I really enjoyed traveling and teaching in Germany and Austria, but I started to reflect and I thought now, with these guys, I want to go too. Alone, I wouldn’t have made this decision, but I feel the dynamic aspect of this group, the openness—in a way we are one. We have common experiences, we know our emotions and habits, and I think we can speak openly and freely. We all really want to deepen our practice. And we don’t want to change the others anymore!

Tenpa?

ST: I spent 12 years traveling and teaching, and I had the strong feeling that although I’d already done two retreats, I hadn’t really reached the end of the process. Yes, there was the blessing of Lama Gendun, who had encouraged me to engage in activity, but I didn’t have the wisdom or qualities to truly meet people’s needs.

For the past 20 years, the thought to go back into retreat was in the back of my mind. When I heard that a few people were going back, it grabbed me. I have to face the fact that I’m nearing the end of my life. To benefit others in this or another life, I really need to do the maximum I can in practice, and I’d better do it now.

Some of you have old parents. How does it feel to know that you might not see them again?

IL: My father died during my first retreat and my mother during the second. It was hard not to be with them, but I’m really sure that it was the best thing for them. Because we have this strong link with people, they are truly helped by the blessing of the practice, though it isn’t something you can express. My mother and sister felt the blessing when my father died; when my mother died, my sister felt exactly the same. And during the ritual I was doing on the third day after my mother’s death, I heard her speaking to me. For me, it was proof that what we’re doing is not just words.

CTD: My father is 86; he’s always encouraged me to do retreat. When I spoke with him about going in again he said, “Uh-oh—2020, I’m not sure I’ll still be here.” He thought I meant two more retreats. I explained that we would be out by 2016, and he said, “Oh! If that’s the case, the whole family will be here!” But it won’t necessarily be easy. My stepmother asked if I could come out if something happens to my father. And I said no, but we will be praying for you.

TR: I needed to clarify my family situation before I could enter retreat. At first my mother was shocked when I told her, but after five minutes she said, “If you’re really happy with this decision, then do it now and not later. If you wait three years I’m not sure I’ll still be here.” I thanked her with tears in my eyes and said that if she didn’t really want me to go, I wouldn’t. But she answered, “No, you are free.”

What are you going to miss about being out there?

TR: Bicycling.

CTD: Relating to other people.

VJ: The next Batman movie.

The others: Nothing.

VJ: Actually, when I’m outside I really miss retreat.

Anything you’d like to add?

VJ: Yes. Three-year retreat is very special, but you don’t have to be special to do it. It’s good to have a basis of dharma practice, but we’ve seen examples of people who just appeared out of nowhere and went into retreat and it worked out quite well. The main thing you need is to have the wish and the ability to work on your own mind.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.