Almost thirty years ago, Tim Olmsted followed the renowned Tibetan teacher Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche to Kathmandu and became his student. Before then he had earned a master’s degree in psychotherapy and community organization from the University of Chicago.

Now Olmsted is a dharma teacher himself. Upon returning to the United States in 1994, he settled in Colorado and founded the Buddhist Center of Steamboat Springs. From 2000 to 2003, Olmsted served as the director of Gampo Abbey, in Nova Scotia, which was founded by Tibetan nun and well-known author Pema Chödrön. Since returning to Colorado, he has continued his role as the resident teacher of the Steamboat Springs sangha. He is the president of the Pema Chödrön Foundation, established to develop the Western monastic tradition, and works closely with Tergar International, the worldwide meditation community of Tulku Urgyen’s youngest son, Mingyur Rinpoche.

Last summer, Tricycle founding editor Helen Tworkov asked Olmsted how it felt to be in the presence of Tulku Urgyen, what it was like to be a dharma bum in Nepal in the old days, and how the great dharma experiment in the West is progressing.

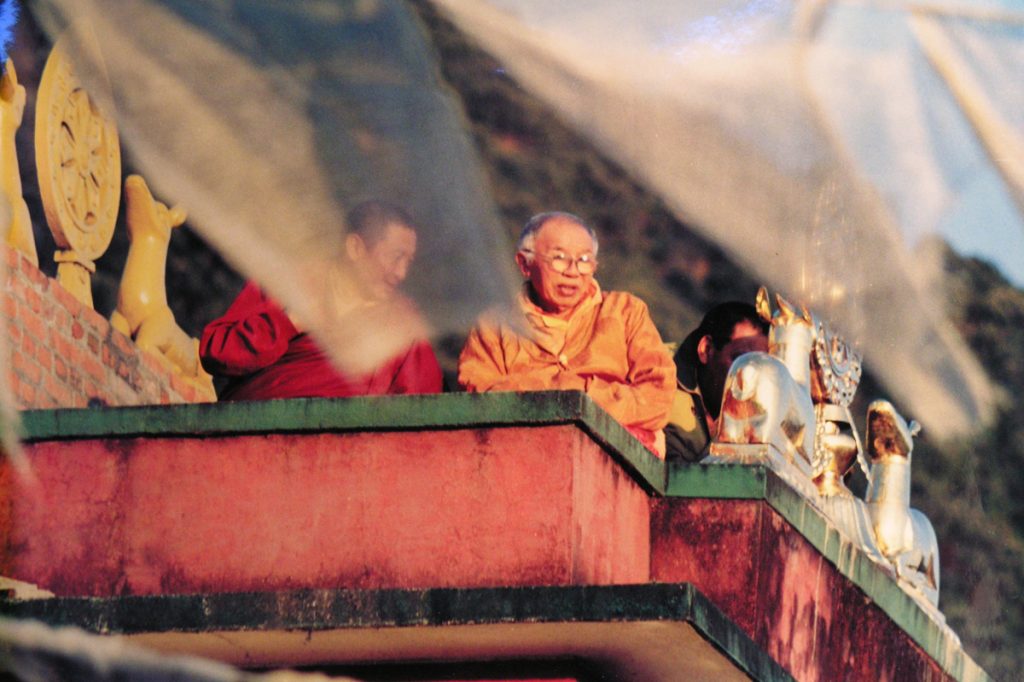

Tell us something about going to Nepal to be with Tulku Urgyen. I arrived in Kathmandu in 1981. Many of the monasteries that had been lost in Tibet were being rebuilt in the Kathmandu Valley, so there was a tremendous amount of activity. The lamas were incredibly available, so we could spend hours talking with them. What had a huge effect on me was to see that each of those great lamas manifested differently: Some were a bit wild, talking fast and walking fast. Others, like His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, were like rocks. Still others were warm and very intimate, like Tulku Urgyen. Then there were boisterous characters like Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche. That diversity helped me relax and realize I didn’t have to act in any one way to be a dharma practitioner. I didn’t have to walk in a certain way or look a certain way or have a particular rap.

But that wasn’t the first time you met Tulku Urgyen. I met him when he came to Boulder at the invitation of Trungpa Rinpoche, in the spring of 1981.

What was your first impression of him? My first impression of him was the same impression that stayed with me during the years that I knew him. Tulku Urgyen was completely modest and totally down-to-earth. He was the kindest man I ever met, yet there seemed no end to his wisdom.

What about him was so compelling that you followed him to Nepal? His teachings during his stay in Boulder felt like the golden key that made sense of what I had learned up to that point. More than that, though, I had the feeling that if I were to ever grow up, I would want to become just like him. I was entranced by everything about him: his gentleness, his wisdom, the graceful way that he moved, and the interest that he took in everyone. Tulku Urgyen was unique in that every time you would visit him, he would take your head in his hands and touch his forehead to yours. He did this whether you were a lama, a minister of Parliament, a beggar off the street, or a dharma bum. Whenever anyone got near him, they would never want to leave. His tiny retreat room would easily fill up with people who would not want to go away. There was an atmosphere of such peace and warmth around him, and, like I said, he treated everyone the same. For a long time I convinced myself that it was because he didn’t see well and couldn’t tell the difference between people.

Were you encouraged to practice? Yes. The general sense was “You can do it.” The old Tibetan teachers weren’t particularly psychological. There was no discussion of “deep wounds” or “working through your issues.” The assumption was that the mind is flexible regardless of one’s personal history. Some people might say that this enabled what the psychotherapist and teacher John Welwood has called “spiritual bypassing”—that is, the tendency to use spiritual ideas to avoid dealing with basic human needs, feelings, and developmental tasks.

And most of us were pretty untamed in those days. Yet there was something incredibly beautiful about that time. There was so much fire and enthusiasm, and we engaged in the spiritual life with a lot of joy. Tulku Urgyen, in particular, was very optimistic. Whenever he spoke, he was always just a couple of sentences away from the only thing he ever talked about: the nature of mind. And there was always the feeling like “Wow, if he thinks we can do it, maybe we can.”

Can you say more about that? I’m not a Buddhist scholar, but particularly with Tulku Urgyen, the emphasis was on making the distinction between a confused, dualistic mind and wisdom mind—a mind that is waking up to the abiding quality of its own nature. He discussed this quite freely. Most of us thought, “This is the secret teaching. Why is he giving it to all of us so freely?” Yet it’s my understanding that His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa asked him to spread this particular teaching, and said that it was a real gift he had—to “point out” to people the true nature of their minds.

Here’s an example of what he taught. It’s from his book Rainbow Painting:

To sum up, we need devotion to enlightened beings and compassion to those who are not. Possessing these two, the main training is maintaining nondistraction. When we forget mind essence we get carried away. But with devotion and compassion, the practice of recognizing mind essence will automatically progress.

Please keep this teaching at the very core of your heart; not at the edge or to one side of your heart, but at the very center. Please think, “That old Tibetan man said devotion and compassion are essential. I’ll keep that right in the center of my heart!”

I have wanted to say this for a long time, but I feel that now people are more willing to listen. It’s because it’s extremely important that I felt it should be said.

I am telling you the truth here. I am being honest with you. I am not lying. If you practice the way I have described here, then each month and year will yield progress. And in the end, no one will be able to pull you back from attaining enlightenment.

This was his core teaching? Yes. He referred everything to the nature of mind. He didn’t talk much about paths and stages and deliberate training in compassion and devotion. For him the emphasis was on recognizing mind’s nature, from which the abiding qualities of compassion and devotion arise spontaneously. One time I said, “Rinpoche, why don’t you teach about compassion and devotion in the same way other lamas do?” And he said, “These days, to have the experience of compassion where tears flow out of your eyes freely, and to have devotion where the hair on the back of your neck stands up—who has that anymore?” He didn’t say that we didn’t have compassion and devotion, or that we shouldn’t train in it constantly, but I believe he was suggesting that we needed to train in a kind of natural, uncontrived compassion and devotion.

How does that fit with your own experience of Westerners, and with how you see the dharma unfolding here? I consider what’s going on in the West a great experiment. But what continues to puzzle me is that in my own studies in Nepal, a sense of weariness with samsaric life was considered the basis of the path. And the quality of faith and devotion for the teachings, the teachers, the lineage, and for one’s own lama was the heart of the path. Today, teachings on these aspects of the path are presented less and less often. So I wonder, if a person isn’t really tired of samsara, what’s the motivation? And if a person doesn’t really have tremendous faith in the teachings and the teachers, what keeps them going during dry spells? So much of the spiritual path can be very dry. I worry that we’re teaching meditation as some kind of linear path that quickly and easily brings great joy and peace. That hasn’t been my experience.

So you’re concerned that the heart of dharma is being jettisoned in favor of feel-good shortcuts? If this presentation of the path is approached by people with enthusiasm—and it works for them—then I’m interested in what we can learn from that. Recently, I was talking to one of Tulku Urgyen’s sons about Buddhism in the West—about how the message has been repackaged in order to be palatable to Westerners. He said that he feared that the experiment might not work, because in this process we might run the risk of losing the power of the dharma.

The power? The power to transform. There’s a completely understandable desire to adapt the dharma to what Westerners can handle. But we run the risk of taking the heart and the power out of it. And if the power goes out of it, people won’t have the personal experiences that will carry them far along the path. Then the whole thing might simply collapse.

Can you be a bit more specific? The Buddhist tradition starts with the historical Buddha: he had a beautiful life, but he saw that it was utterly pointless. He was willing to give it all up and endure tremendous hardship to find out what was on the other side. That example of dedication and bravery is what this path is founded on. And so if we approach dharma on the basis of what is comfortable for us—what we like, what we don’t like, what fits into our lives conveniently without having to give anything up—that may be some kind of path, but I’m not sure it reflects the example of the Buddha’s own life. I also wonder if it will bear fruit.

Do you think sacrifice is critical? We need to give up something. We can’t have it all. We can’t try to layer wisdom on top of confusion. The spiritual path is about what we give up, not what we get. We seem to always want to get something—spiritual insights or experiences—as a kind of commodity. We sign up for a retreat and expect that we’ll have this or that wonderful experience or this or that special teaching. But don’t these wisdom traditions teach us that, in essence, there’s nothing to get? We need to give up what obscures the abiding wisdom and the abiding reality—the wisdom and reality that is already here. That’s the gospel of the Buddha, but I wonder if we’re listening to it.

How do you work on this with your students? We have a wonderful group of people in Steamboat [Springs], but I don’t feel like I’ve been particularly effective. That feeling reflects my own confusion about how this path is going to play out. Generally the folks in our sangha are neither yogis nor scholars. Yet something seems to be happening for them that’s very positive.

What I sense is that people coming into dharma centers these days want to be in a community where there’s profound conversation and virtuous activity. So I think we need to focus on developing sangha—community. In the past, we’ve focused primarily on the dharma, the teachings, the Buddha, or the guru. It’s taken me a long time to understand people who aren’t haunted dharma bums like myself; studying and practicing the dharma is all I ever wanted to do. But I think I’m learning as fast as they’re learning, and we’re meeting somewhere in the middle.

You have also been a passionate advocate for monasticism. How important is it for the development of Buddhism in the West? Tulku Urgyen’s dying wish was that there would be an enormous monastery built in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha. I asked him once why he was so interested in this, especially as he himself was not a monk, and he said, “People need something to have faith in.” And so from that point of view, the monastic tradition is important as a symbol of those who have made sacrifices to follow a profound path—whether it’s Buddhist, Christian, or otherwise. In Asia, these symbols of spiritual devotion and endeavor are part of the atmosphere. It changes you. Even as a layperson in that environment, you’re profoundly affected. So I think the monastic tradition, or the contemplative tradition, has something to offer the outside world as a symbol of what’s sacred and profound. The monastic tradition is extraordinary powerful and beautiful, but it’s too early to see whether or not it will take hold in the West.

Without the symbols, how do you promote the values of sacrifice and renunciation? It’s difficult. In many places throughout the world now, the lifestyle for yogis and monastics is pretty cushy, so deep renunciation is not necessarily demanded. If we talk about really giving up territory, privilege, and prestige within a Western community—real inner renunciation— I don’t know that we have any institutions that actually ask anybody to do that, except, oddly enough, maybe the military. For example, sometimes people might take on spiritual symbols—a robe and a shaved head—and use them as credentials. But what is deep renunciation? What’s the relationship between giving up outer comforts and inner comforts, and then giving up innermost comforts such as any sense of ground or territory?

Do you have a sense of that process for yourself as a layperson? It’s really hard. My wife is a successful real estate agent in a small mountain town in Colorado. We have a beautiful life in a beautiful place with a big home and a dog. I never forget how lucky I am. At the same time, I think we get soft. Maybe it’s age. Maybe it’s the result of the path—having done some practice, maybe samsara isn’t quite so unbearable, quite so biting. Tulku Urgyen’s son Tsoknyi Rinpoche has a wonderful term for folks like us—“Grand Samsara Masters,” meaning that a lot of us middle-aged dharma students have succeeded along the path and become masters of samsara. That’s frightening in a lot of ways. We’re getting older, and things are getting more comfortable. Our friends appear more frequently in the obituaries, and we’re still not paying attention. So I asked Tsoknyi Rinpoche, “What do we do?” And he said very clearly, “Always remember bodhicitta and impermanence.” Bodhicitta is the mind of enlightenment—the wish to attain complete enlightenment in order to be of benefit to all sentient beings trapped in cyclic existence.

But I’m always haunted by the great challenge of mixing dharma and worldly life, and also the reality that I run the risk of never really actualizing the very teachings that my teachers gave me. I look at myself and say, If someone like me doesn’t do it— give it my all—then how can I expect anyone else is going to do it? We’ve spent time with the great teachers, and they entrusted us with their heritage. That is so unimaginably rare, and yet we seem to be turning away from even the basic example of the Buddha.

So if our stories reflected the life of the Buddha, then Prince Siddhartha would have left the palace, gotten enlightened, returned to the palace, lived a life of comfort and luxury, and taken his father’s throne as the Master of Samsara? Yes. Then again, in virtually every conversation I have with old dharma friends, I am the constant curmudgeon. Maybe it’s just my own neurotic thing.

Picking up on what you said about your students in Steamboat, there does seem to be a greater sense today of engaging in dharma for the benefit of others and for the society: maybe we’re not monks, maybe we’re not practicing in caves, but we’ve come down from the mountain to learn how to integrate practice and daily life. This is right at the heart of this great dilemma: On the one hand, it’s become a truism that we have to bring whatever wisdom we have attained back into the society. But really, we have to go up to the mountain first; we have to have something to offer, something to bring back. There’s so much concern lately with coming back into the society that we’re losing the part about going away from it—living the solitary life of a contemplative, going on retreat, going into those circumstances that nourish and encourage the actualization of the teachings. We all talk about bodhicitta, and aspire to develop compassion. But it’s been taught that the defining quality of bodhicitta is the deep conviction to develop complete realization—buddhahood—for the benefit of all beings.

Tulku Urgyen always said that the power of enlightened mind is not conditioned by near and far. It’s not obstructed. So a person in retreat, developing realization and the qualities of mind that go with it, affects all sentient beings because of the nature of that unimpeded mind. So, in fact, maybe we don’t need to come back down from the mountain. Tulku Urgyen said that even taking seven steps toward a retreat center and having the heartfelt wish to actualize the teachings and realize the nature of mind for the benefit of all beings is more profound than giving all the money in the world to the buddhas. Just that desire and taking seven steps. I really believe that’s true. So I don’t think we know what it means to come down from the mountain. But I do know that if we never go up to the mountain, we won’t have anything to talk about.

It’s as if my mother had a brain tumor and because I wanted to help her, I took out a scalpel and began operating. If we really want to be helpful, first we have to go to medical school. We’ve got to train. We don’t want to pretend that we have the skill or the wisdom to do things when we don’t.

Do you think that all the talk about coming down from the mountain covers up our resistance to going up to the mountain in the first place? I think the talk may cover up the fact that in our hearts we know that we really do need to follow the example of our teachers and our teacher’s teachers. Maybe we make sophisticated rationalizations for why putting it off is the wise thing to do. I fear that if we start with lofty goals, and then proceed to justify our own lack of full engagement, we’ll all become disheartened and the wisdom tradition will end up as just a myth.

For me these are the central issues we need to address: Going up to the mountain and coming down from the mountain. What does it mean? How do we carry the dharma and the wisdom tradition in a way that can be appreciated, understood, and assimilated into the world? We must keep this as the central dilemma that we strive to resolve. How can we actualize the teachings that we’ve been given? Maybe we won’t become “fully realized,” as it were, but something needs to shift deeply in our hearts. This is the measure of my own path: every year, if my teacher were to ask me, I would dearly hope to be able to say that something in my heart or mind has actually shifted.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.