Attachment and anger are two sides of the same coin. Because of ignorance, and the mind’s split into object-subject duality, we grasp at or push away what we perceive as external to us. When we encounter something we want and can’t get, or someone prevents us from achieving what we’ve told ourselves we must achieve, or something happens that doesn’t accord with the way we want things to be, we experience anger, aversion, or hatred. But these responses serve no benefit. They only cause harm. From anger, along with attachment and ignorance, the three poisons of the mind, we generate endless karma, endless suffering.

It is said that there is no evil like anger: by its very nature, anger is destructive, an enemy. Since not a shred of happiness ever comes from it, anger is one of the most potent negative forces.

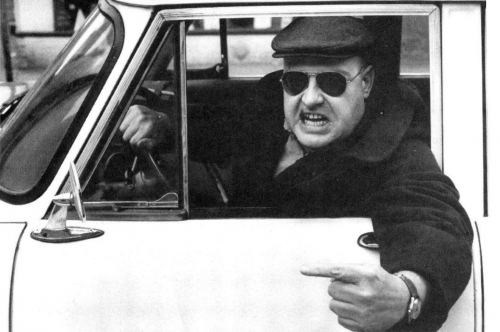

Anger and aversion can lead to aggression. When harmed, many people feel they should retaliate by taking an eye for an eye. It’s a natural response. “If someone speaks harshly to me, then I’ll speak harshly in return. If someone hits me, I’ll hit him back. That’s what he deserves.” Or, more extreme: “This person is my enemy. If I kill him, I’ll be happy!”

We don’t realize that if we have a tendency toward aversion and aggression, enemies start appearing everywhere. We find less and less to like about others, and more and more to hate. People begin to avoid us, and we become more isolated and lonely. Sometimes, enraged, we spit out rough, abusive language. The Tibetans have a saying: “Words may not carry weapons, but they wound the heart.” Our words can be extremely harmful both through the damage they do to others and the anger they evoke. Very often a cycle develops: one person feels aversion toward another and says something hurtful; the other person reacts by saying something out of line. The two start fueling each other until they’re waging a battle of angry words. This can be extended, of course, to the national and international levels, where groups of people get caught up in aggression toward other groups, and nations are pitted against nations.

When you give in to aversion and anger, it’s as though, having decided to kill someone by throwing him into a river, you wrap your arms around his neck, jump into the water with him, and you both drown. In destroying your enemy, you destroy yourself as well.

It is far better to defuse anger before it can lead to further conflict, by responding to it with patience. Understanding our own responsibility for what happens to us helps us to do so. Now we treat our connection with a perceived enemy as if it came out of nowhere. But in some previous existence, perhaps we spoke harshly to that person, physically abused him or harbored angry thoughts about him. Instead of finding fault with others, directing anger and aversion at situations and people we think are threatening us, we should address the true enemy. That enemy, which destroys our short-term happiness and prevents us, in the long term, from attaining enlightenment, is our own anger and aversion.

Then the confrontation comes to nothing. There is no fight, you no longer perceive the person you’ve been confronting as an enemy, and the true enemy has been vanquished—a great return for a little bit of effort. In the long run, both you and the other person are less likely to get repeatedly into situations where conflict could develop. You both benefit.

Our habitual tendency is to contemplate in counterproductive ways. If someone insults us, we usually dwell on it, asking ourselves, “Why did he say that to me?” and on and on. It’s as if someone shoots an arrow at us, but it falls short. Focusing on the problem is like picking the arrow up and repeatedly stabbing ourselves with it, saying, “He hurt me so much. I can’t believe he did that.”

Instead, we can use the method of contemplation to think things through differently, to change our habit of reacting with anger. Since it is difficult at first to think clearly in the midst of an altercation, we begin by practicing at home, alone, imagining confrontations and new ways of responding. Imagine, for example, that someone insults you. He’s disgusted with you, slaps you, or offends you in some way. You think, “What should I do? I’ll defend myself—I’ll retaliate. I’ll throw him out of my house.” Now try another approach. Say to yourself, “This person makes me angry. But what is anger? It is one of the poisons of the mind that generates negative karma, leading to intense suffering. Meeting anger with anger is like following a lunatic who jumps off a cliff. Do I have to do likewise? If it’s crazy for him to act the way he does, it’s even crazier for me to act the same way.”

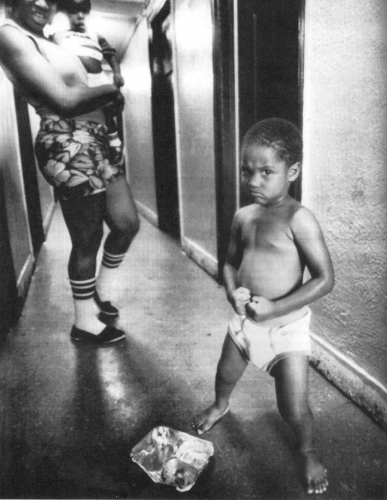

Remember that those who are acting aggressively toward you are only buying their own suffering, creating their own worse predicament, through ignorance. They think that they’re doing what’s best for themselves, that they’re correcting something that’s wrong, or preventing something worse from happening. But the truth is that their behavior will be of no benefit. They are in many ways like a person with a headache beating his head with a hammer to try to stop the pain. In their unhappiness, they blame others, who in turn become angry and fight, only making matters worse. When we consider their predicament, we realize they should be the object of our compassion rather than our blame and anger. Then we aspire to do what we can to protect them from further suffering, as we would a child who keeps misbehaving, running again and again into the road, hitting and scratching us as we attempt to bring her back. Instead of giving up on those who cause harm, we need to realize that they are seeking happiness but don’t know how to find it.

The role of the enemy isn’t a permanent one. The person hurting you now might be a best friend later. Your enemy now could even, in a former lifetime, have been the one who gave birth to you, the mother who fed and took care of you.

By contemplating again and again in this way, we learn to respond to aggression with compassion and answer anger with kindness.

Another approach we can use is to develop awareness of the illusory quality of our anger and the object of our anger. If, for example, someone says to you, “You’re a bad person,” ask yourself, “Does that make me bad? If I were a bad person and someone said I was good, would that make me good?” If someone says coal is gold, does it become gold? If someone says gold is coal, does it become coal? Things don’t change just because someone says this or that. Why take such talk so seriously?

Sit in front of a mirror, look at your reflection, and insult it: “You’re ugly. You’re bad.” Then praise it: “You’re beautiful. You’re good.” Regardless of what you say, the image remains simply what it is. Praise and blame are not real in and of themselves. Like an echo, a shadow, a mere reflection, they hold no power to help or harm us.

As we practice in this way, we begin to realize that things lack solidity, like a dream or illusion. We develop a more spacious state of mind—one that isn’t so reactive. Then when anger arises, instead of responding immediately, we can look back on it and ask: “What is this? What is making me turn red and shake? Where is it?” What we discover is that there is no substance to anger, no thing to find.

Once we realize we can’t find anger, we can let the mind be. We don’t suppress the anger, push it away, or engage it. We simply let the mind rest in the midst of it. We can stay with the energy itself—simply, naturally, remaining aware of it, without attachment, without aversion. Then we find that anger, like desire, isn’t really what we thought it was. We begin to see its nature, to realize its essence, which is mirror-like wisdom.

It may sound easy to do this, but it’s not. Anger stimulates us and we fly—one way or the other. We fly in our mind, we fly off to a judgment, we fly to a reaction, we fly to this or that, becoming involved with whatever has upset us. Our habit of lashing back in this way has been reinforced again and again, lifetime after lifetime. If our understanding of the essence of anger is only superficial, we’ll find out that we aren’t capable of applying it to real-life situations.

There is a famous Tibetan folk tale of a man meditating in retreat. Somebody came to see him and asked, “What are you meditating on?”

“Patience,” he said.

“You’re a fool!”

This made the meditator furious and he immediately started an argument—which proved exactly how much patience he had.

Only through continual, methodical application of these methods, day by day, month by month, year by year, will we dissolve our deeply ingrained habits. The process may take some time, but we will change. Look how quickly we change in negative ways. We’re quite happy, and then somebody says or does something and we get irritated. Changing in a positive way requires discipline, exertion, and patience. The word for “meditation” in Tibetan is a cognate of the verb “to become familiar with” or “to acclimatize.” Using a variety of methods, we become familiar with other ways of being.

There’s an expression: “Even an elephant can be tamed in various ways.” When goads or hooks are used skillfully, this enormous, powerful beast can be led along very gently. It is said that when elephants are decorated for festive occasions, they become docile, moving as though they were walking on eggshells. Or if they’re in a large crowd of people, elephants are very easily controlled. So something that is big and unwieldy can actually be managed well with the proper means. In the same way, the mind, often unwieldy and wild, can be tamed with skillful methods.

We don’t need a psychic to tell us what our future experience will be—we need only look at our own minds. If we have a good heart and helpful intentions toward others, we will continually find happiness. If instead, the mind is filled with ordinary self-centered thoughts, with anger and harmful intentions toward others, we will find only difficult experiences.

If we check the mind again and again, continuously applying antidotes to the poisons that arise, we will slowly see change. Only we ourselves can really know what is taking place in the mind. It’s easy to lie to others. We can pretend that a thick leather bag is full, but as soon as someone sits on it, he’ll know whether it’s truly full. Similarly, we can sit for hours in meditation posture, but if poisonous thoughts circulate in the mind all the while, we’re only pretending to do spiritual practice. Instead, we can be honest with ourselves, taking responsibility for what we see in our own minds instead of judging others, and apply the appropriate remedy for change.

♦

This is an excerpt from Gates to Buddhist Practice by Chagdud Talku. Copyright 1993 by Chagdud Talku. Used with the permission of Padma Publishing.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.