By her own account, Elaine Pagels is “incorrigibly religious.” For her, the historical study of religion is a passionate pursuit, one that engages the whole of one’s being. The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion at Princeton University, Pagels is widely regarded as one of the world’s foremost scholars of the history of early Christianity. Indeed, it would not be an overstatement to say that she has forever altered how we understand the historical foundations of Christian tradition. In the process, she has eloquently demonstrated how understanding humankind’s religious past can pave the way for a more inclusive and open-minded understanding of religious life today.

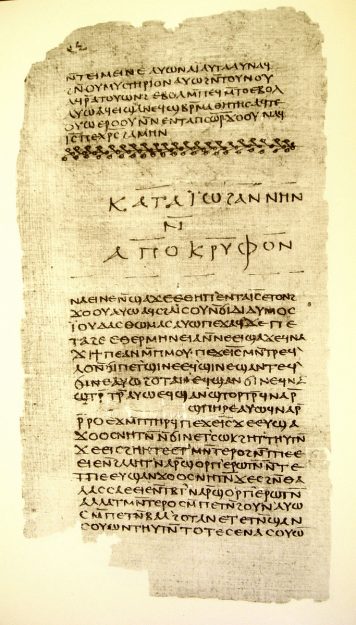

Pagels earned her doctorate in religious studies from Harvard in 1970. During her graduate studies she encountered the Nag Hammadi Library, a then little-known body of texts named after the Egyptian town near where they were accidentally unearthed in 1945 by a local farmer. These texts, while contemporaneous with the canonical texts of the New Testament, provide a vastly different view of Jesus’ life and teachings and of the early community of his followers. The Nag Hammadi manuscripts demonstrate that early Christianity, far from being the unified church of legend, was a movement that teemed with diversity. Comprising gospels, mystical tracts, poetry, and mythic tales, these writings were denounced and eventually banned by early church leaders, as they sought to consolidate their authority and establish institutional orthodoxy. Pagels devoted herself to the study of the Nag Hammadi writings, and in 1980 she won the National Book Award for The Gnostic Gospels, a landmark work of scholarship that revealed to the world the spiritual richness of these suppressed texts.

In the years since then, Pagels has continued to explore how the ideas and events of the ancient world shape our lives today. Taking a stance that affirms the value of religious traditions even as it holds them up to rigorous critique, Pagels’s work demonstrates how religions—and Buddhism is certainly no exception—selectively shape perceptions of their past in order to make points about the present. Her work carves out a space in which we can regard religious traditions with both a greater appreciation for their benefits and a keener eye for those aspects that serve a narrow ideology.

In February, I had the pleasure of speaking with Professor Pagels. In conversation, Professor Pagels demonstrates many of the same traits that characterize her writings: an imposing intellect, a storyteller’s gift, and a love for her subject. Although we explored many topics, the red thread running through our conversations was the idea that the study of our religious history reveals new possibilities for engaging the spiritual dimension of our present-day lives. —Andrew Cooper

You’ve observed that many historians of religion are mainly concerned with debunking traditional religious beliefs. But you seem to approach historical scrutiny as a means of actually enriching the life of religion. As you say, it is not my purpose to debunk religion. But historical study places a religion into a context that many of its followers may not have considered, and by doing so, it places into question elements of its traditions. In the case of Christianity, that comprises two thousand years of history. Historical study shows that what we call, say, Christian tradition or Buddhist tradition in fact entails a huge range of practices and beliefs. When Christians discuss Christian tradition or Buddhists discuss Buddhist tradition, they usually make many unconscious and implicit selections out of that range. Historical study shows that the background is denser and more complex than we might otherwise assume. It brings out other elements of the tradition, elements that are not ordinarily in the foreground. We can, therefore, understand more clearly the social, cultural, and political situation in which particular practices and beliefs emerged.

Historical study should have the effect of making what is very familiar look different or even in some ways strange. Demonstrating contingency, by shifting the picture maybe half a degree, gives one a very different perspective. Religions are continually being reinvented, rediscovered, revised, and transformed, and it is useful to be aware of this. But religious orthodoxy often is based on a pretense that just the opposite is true.

One can certainly find this in Buddhist history. As schools and movements have emerged and vied for legitimacy and institutional power, they’ve constructed a story of the past to give them a privileged standing in the present. For a Buddhist school or doctrine to be seen as authoritative, it must in some way be traceable back to the historical Buddha. So scriptures that appeared centuries later were said to have been hidden or kept secret until the world was ready. Or Zen, since it had no central scripture, fabricated a lineage of transmission. But whatever the strategy, legitimacy is established by rewriting or obscuring or otherwise fiddling with history. And lacking the tools of modern scholarship, after a generation or two, who would be the wiser? The Church father Tertullian said, Christ taught one single thing, and that’s what we teach, and that is what is in the creed. But he’s writing this in the year 180 in North Africa, and what he says Christ taught would never fit in the mouth of a rabbi, such as Jesus, in first-century Judea. For a historically-based tradition—like Christianity, and as you say, Buddhism—there’s a huge stake in the claim that what it teaches goes back to a specific revelation, person, or event, and there is a strong tendency to deny the reality of constant innovation, choice, and change. So the idea of historical contingency can be very threatening. But it is important, because it fosters a broader, less sectarian view.

Would you say a historical perspective can reinvigorate a religion’s practices and traditions, even as it calls into question many of the claims upon which those practices and traditions rest? Yes, I think it can. Let me give you an example. In the Gospel of John, we often find Jesus declaiming, as though he’s standing in the middle of a room or the middle of a desert and saying, “I am the truth, I am the way, I am the light, I am the water of life.” And it might never occur to you to wonder, Well, whom is he addressing? Why is he saying this over and over? Why is this written this way? And why is this supposed to be an important teaching? But when I began studying the Gospel of Thomas, where very different views are articulated, it became evident that much of this had to do with arguments over how to understand who Jesus was and what to bring out in his teachings.

Much of my work has focused on elements of early Christian tradition that have been discarded, relegated to heresy, or pushed to the margins, largely for institutional reasons. But many of these elements I find spiritually powerful, and so I think there is great value in their recovery. Doing that kind of work entails peeling away prejudices and assumptions, many of which are quite unconscious. Some of these recovered texts, by the way, such as the Gospel of Thomas, sound in many ways a great deal like Buddhist teachings. [see “According to Thomas”, on last page]

These arguments about understanding Jesus are tied to the notion of the messiah. In The Origin of Satan, you trace Satan’s evolution from being a minor and vaguely drawn character in the Hebrew Bible to his portrayal in the New Testament as a cosmic principle. Didn’t the notion of the messiah undergo a similar, or at least parallel, transformation? That’s an interesting question. Yes, the idea of the messiah went through many transformations. The Hebrew word mashiah means “anointed one.” The term could refer to priests, who were anointed with oil when they were consecrated. But in the Hebrew Bible, mashiah most often refers to the King of Israel. And that’s what it meant in New Testament times. That’s the sense in which Jesus would have been seen as the messiah: the King of Israel, the king of the Jewish people. He was, in this regard, one among many candidates. Obviously, over time, Christians came to view the idea of the messiah in a very different way.

There is also the question of whether Jesus himself actually said he was the messiah. In the fourteenth chapter of Mark, Jesus is asked, and he accepts the term, but other accounts of the same event say that he didn’t. Whatever the case, the question would have referred to whether he was the King of Israel. No New Testament scholar—or rather, none I know—thinks Jesus ever said he was the Savior of the world, or anything like it.

Whether or not Jesus actually said he was the messiah, the Romans were concerned about him being seen that way. That is why they would have considered Jesus dangerous, and that is most likely why he was crucified. The Romans were brutal in dealing with any threat to their power. When they crucified Jesus, they put up a sign, in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, that said “King of the Jews.” Crucifixion was a very public way of advertising what happens to people who claim to be leaders and stir up rebellion.

So how and why did the messiah become a cosmic principle? How did Jesus go from being a revered teacher and possibly a leader of his people to being the Savior of all humanity? That’s an enormous question! I think that it is a big part of what motivates many of us to study the history of Christianity. In her book From Jesus to Christ, the historian Paula Fredriksen tries to track that exact thing. How did a rabbi from Nazareth, a man with an obscure and humble background, come to be seen as the Savior of the world? It’s astonishing.

Certainly, the teachings of Paul were crucial. Paul called Jesus the Savior of the world, and he translated his convictions about Jesus into terms that Gentiles could understand. Paul portrayed Jesus’ crucifixion as a sacrificial death that atoned for all sin and claimed that those who believed in Jesus could find a place in salvation. My colleague at Princeton John Gager has written several books based on his view, which is shared by others, that Paul saw Jesus’ life and teaching as a divine revelation that would extend the salvation previously enjoyed only by Israel to all the nations, thereby fulfilling prophesies in Isaiah and also God’s promise to Abraham that “In you all the nations of the earth shall be blessed.” That’s John Gager’s conviction, and it’s a very interesting perspective.

After Jesus was crucified, his disciples were left with a terrible feeling of disappointment. The Gospel of Luke has them say, You know, we heard these things about Jesus of Nazareth. We thought he was going to be the one to redeem Israel. But we were wrong. The idea that Jesus would fulfill the role of the King of Israel—well, it didn’t happen. So they needed a different way to understand who and what he was. They needed to make sense out of this devastating event. So they changed the definition of “messiah” and created a different narrative about his role.

In Buddhism’s history, one sees the figure of the Buddha undergoing a kind of parallel transformation. Early on, he is portrayed primarily as a great spiritual teacher. But over time, the focus shifts, and the emphasis falls more on the Buddha as a cosmic principle rather than a human being. The circumstances under which the change occurs are, of course, entirely different from the case of Christianity, but the process is parallel. I’m not surprised. A religion’s symbols and stories, to survive, take on very different meanings over time. The canonical texts of Christianity or Buddhism would likely not have survived had they not been continually reinterpreted and reread in terms of the time and place of the reader. You could almost call this a process of creative misreading. For me, studying how these texts survive and transform is completely fascinating.

For most followers of most religions, it was long assumed that their sacred texts were both religiously valid and historically accurate. But modern scholarship has shown the two issues to be separate. Today, science has replaced religion as the source of our best knowledge about how the world and the cosmos work. History is better at telling us about our human past. Social systems and, to an extent, moral systems have been shown to be human creations and not expressions of divine will or natural order. So what real needs must religion fill today? Having been brought up in a family of scientists, who assumed that scientific explanations for the origins of the universe and human beings had simply rendered religion irrelevant, I’ve thought a lot about that question. The physicist Steven Weinberg says that the more we know about the universe, the more we know it is pointless. Cosmology can tell us about the Big Bang and exploding gases and how the world came into being. Anthropology and biology can tell us about human evolution. In other words, science can tell us about how things work, but it cannot tell us what any of it means.

Religion addresses a whole different range of issues. It addresses questions of meaning and value, and those are questions we still must ask. They are not out of date. Is life meaningful in some coherent way? The stories of religion articulate social and cultural values in a kind of code language.

As you say, we now experience a divide between the factual accounts given by scientific study and the stories told by religion. But for many people, those stories hold a feeling of truth, which comes from the sense of meaning they articulate.

As you were talking, I remembered something Picasso once said about art: “Art is the lie which tells the truth.” In that vein, the myths and symbols of religion can be regarded as a kind of template for finding meaning. Yes, and that’s something that science doesn’t do. The poet Marianne Moore said that poetry is imaginary gardens with real toads in them, and I think this applies to the stories of religion as well. This is not to say that all religious stories are purely fanciful; some of them may be quite accurate. But the point is that these gardens, including the Garden of Eden, contain human realities.

In an interview with Bill Moyers, you said that while you disagree with the fundamentalist view that the stories of their particular religion are all literally true, you agree with the feeling that such stories are vessels for transmitting fundamental understandings. Well, yes. But that sounds a little too pious, at least from my perspective now. I don’t think all the stories in the Bible, for example, express profound religious truth. Some of them are bizarre and maybe even dangerous. There’s no reason to assume that everything about a religion is benign. There are elements in any tradition that are malignant and can have very destructive consequences. I think there needs to be room in religion for skepticism. We need to approach the matter critically and with discernment.

Even those stories that are pure fancy have a seriousness about them. Let me give an example. In the second chapter of Genesis, God creates a man, Adam, but seeing that Adam has no suitable companion, God puts Adam into a deep sleep and then draws out of his body a rib, which God then makes into a woman. This is followed by a commentary: “Therefore a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and they shall become one flesh.” So this is a sort of explanation of the origin and nature of sexual desire. Man and woman used to be one flesh, and they desire to return to that state.

In Plato’s Symposium the same subject is addressed, but the view put forth is very different. The comic poet Aristophanes tells of how, in the beginning, the gods made human beings, and these humans were completely round. They had four arms and four legs, two heads and two sets of genitals, and they moved by bounding around like cartwheels. They were very boisterous and proud and thought very well of themselves. But they neglected to worship the gods. So Zeus decides to kill the lot of them. Some of the other gods, though, point out that, should he do that, there would be no one left to perform the sacrifices. Zeus, then, comes up with a different plan. He slices these round human beings right down the middle, then he sort of turns their arms and legs and heads and genitals around. So now these new humans, who have been very much weakened by being sliced in two, do nothing but run around looking for their other half. And that’s why there’s erotic desire.

It’s a funny story, and I don’t know whether Plato viewed it purely as a myth or as an actual event or as something somewhere in between. But what I find most interesting is that these original spheres, the first people—some of them were half male and half female, so when they were cut in two, the male halves looked for a female half, because that’s what had been cut off, and the female halves looked for a male half. But some of the spheres were originally all male and some were all female, and when they looked for their other half, the male halves looked for a male and the female halves looked for a female.

Neither of these creation myths has any factual basis, of course. But each speaks of the power and quality of erotic desire, and each carries a strong cultural message and social picture. So the garden is imaginary, but the toads—that is, the social meanings—are real. And they are very different. In the biblical story, only desire between male and female is addressed, and desire between two females or two males would be aberrant. But in Plato’s account, erotic desire between people of the same sex is as valid and natural as that between people of opposite sexes. So that’s what I meant about the seriousness of religious stories.

When New Yorker editor David Remnick profiled you some years back, you spoke of religious mythologies as being part of the “architecture of our thinking.” In other words, whether or not we believe in them intellectually or accept them consciously, they work on us unconsciously, shaping the way we understand and perceive ourselves and the world. Again, let me qualify what I said. I don’t think a culture’s religious mythology necessarily works on everyone in that culture or works on everyone to the same degree. But, yes, I think the stories and symbols of religion can affect us more deeply than we might know or believe.

When I began working on The Origin of Satan, I thought of Satan as a quaint, cartoonlike figure. So I was surprised to see the power the myth still holds. I learned that when people said things like “Satan is trying to take over this country,” they didn’t mean some kind of vague supernatural energy out there. They meant certain people who were motivated by the forces of evil, and they could give you names and addresses. The mythology of Satan clearly has a much deeper resonance than I, and many like me, had thought.

Look at the way the mythology plays in the unconscious of people, and you’ll understand the way it’s used politically. This idea of the forces of good fighting the forces of evil is something we’ve heard a lot of in recent years: “We’re going to wipe out the evildoers.” And as we’ve seen, when the rhetoric of the battle of good against evil is translated into strategic or military decisions, there’s no room, or even a reason, to negotiate.

I remember one night in 1995, during the time I was working on the book, reading an article by Cyrus Vance, who was then trying to negotiate a settlement among the warring factions in the former Yugoslavia. After becoming completely frustrated by the obstinacy of the political leaders, he went to the religious leaders, the Croatian Roman Catholics, the Serbian Orthodox, and the Muslims, and he said, You’ve got to help stop the bloodshed and get the factions to come to some agreement. But the response from each of the three groups was the same: You don’t understand. We can’t compromise with those others—they’re devils.

Each of those religious groups has within it this paradigm of good versus evil. It’s not a complex way of viewing the world, and it can be incredibly dangerous as a way of dealing with complex conflicts. And it concerns me, because I see an increase in the way the power of affiliation has come to work through religion.

That is a big change, because it had long seemed that religion had all but ceased to be a significant force in history. Throughout the twentieth century, economics was seen as the engine of history. Even the religious wars of the past—the Crusades, say—were viewed as really being about land and resources and treasure. Over the last couple of decades, religion has reasserted itself in world affairs. But the way this is happening is, as you point out, troubling. Do you think that this situation places new demands on those of us who seek to bring a modern critical outlook into religious life and practice? Yes, I do. People who have come to recognize the need to engage the spiritual dimension of life while also maintaining a critical perspective have something to contribute to the religious conversation. As I said earlier, I was raised in a family where it was thought that reason had superseded religion. Those who, like my family, believe in rationalism, often regard science and religion as opposites, and so they underestimate, or entirely disregard, the power of the spiritual dimension. And, of course, many religious people see the same opposition between science and reason, on the one hand, and religious faith, on the other. They just see it from a different angle.

But it doesn’t have to be an either/or decision. There are many ways to practice a religious life. Religion is not at all as narrow as many people, religious and secular, believe. Religious experience is something deeper and more compelling than what can be expressed in any particular set of beliefs.

When I began work on my book on the Gospel of Thomas, Beyond Belief, I was struggling with the question of what I loved about Christian tradition and what I could not love. Writing the book helped clarify for me that what I could not love was the rigid dogma and the idea that Christianity was the only path to God. And what I loved was the power of the tradition to move us, and even transform us, spiritually. But I don’t think that this is true only of Christianity. A religious tradition contains forms and teachings that can lead people into the spiritual dimension of life. In today’s world, that capacity and that experience need to be affirmed.

According to Thomas

Jesus said, “Whoever knows everything, but is lacking within, lacks everything.” (Thomas 67)

Jesus said, “I am the light that is over all things. I am all. From me all came forth, and to me all extends. Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there:· (Thomas 77)

He said to them, “What you look forward to has already come, but you do not recognize it.” (Thomas 52)

“For this reason I say, whoever is [undivided] will be full of light, but whoever is divided will be full of darkness.” (Thomas 61)

Jesus said, “If two make peace with each other in a single house, they will say to the mountain, “Move from here! and it will move.” (Thomas 48)

From Beyond Belief, © 2003 by Elaine Pagels, published by Random House

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.