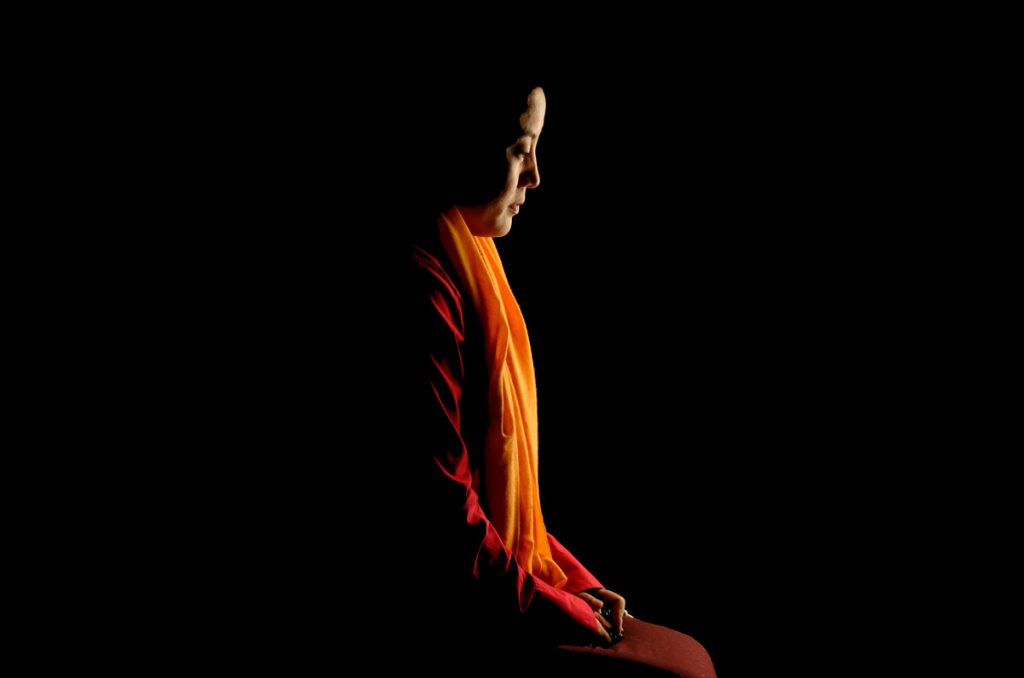

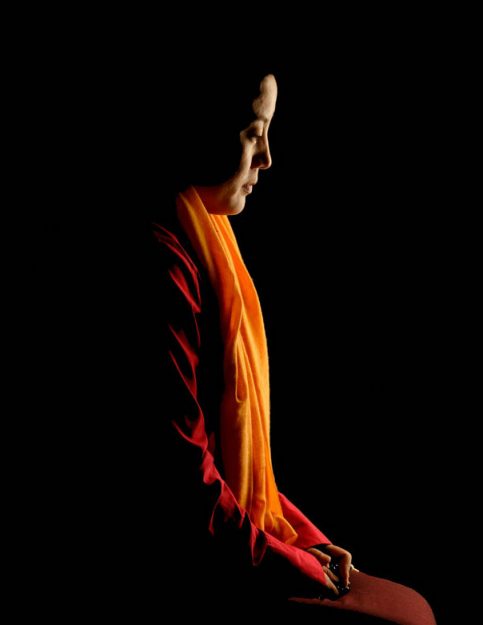

Ask Ani Choying Drolma how she made the transition from battered daughter of poor Tibetan refugees to international singing sensation, founder of the Nuns’ Welfare Foundation of Nepal, and coauthor of Singing for Freedom, an unabashedly candid autobiography that made waves in France before being published in a dozen other countries (an English translation was published in June 2009 in Australia and New Zealand by Murdoch Books), and she will tell you that the boundless kindness and unconditional love of her teacher, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, were her salvation.

In Ani Choying’s culture, humility is a cardinal quality. But the custom of humility often translates as low expectations and the unquestioned acceptance of male dominion. Choying could not reconcile herself to this imbalance of power, which she experienced first as a young girl subjected to daily beatings by her father—even while she tried her best to help with the housework and care for her little brothers—and later as a teenage nun in a religion that has traditionally made much of its monks.

Ani Choying’s special qualities have made it possible for her to break the mold. Along with an indomitable, feisty spirit, she has a magnificent voice, a willingness to experiment (she was the first nun to drive in Nepal), and an intense desire to help other people realize their potential. Under the umbrella of the Nuns’ Welfare Foundation, her many projects in Nepal include running the Arya Tara School for young nuns, supporting a home for elderly mothers abandoned by their families, and founding a clinic for people with kidney ailments.

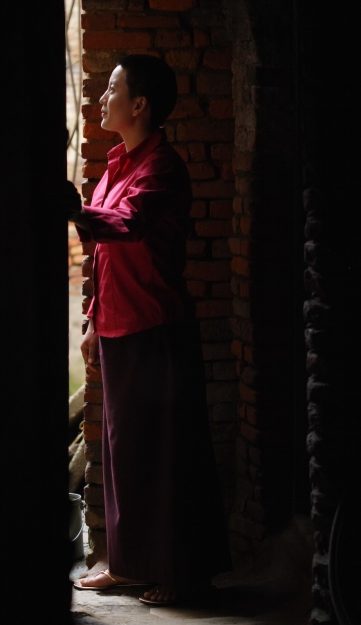

Last April, Pamela Gayle White visited with Ani Choying Drolma at her home in Boudhanath, Nepal, a few minutes’ walk from the Great Stupa.

In your book you speak openly about your childhood with a father who routinely beat you and a mother who was unable to intervene. How has your practice of Buddhism helped you make sense of the past? What happened happened; I can’t undo it. I’ve learned that it’s stupid to live in that unpleasant experience forever. The most painful situation took place long ago, but as you relive it you make yourself suffer over and over again. The main question is how much you want to break free of your patterns and dissatisfaction regarding what you’ve been through.

In your book you speak openly about your childhood with a father who routinely beat you and a mother who was unable to intervene. How has your practice of Buddhism helped you make sense of the past? What happened happened; I can’t undo it. I’ve learned that it’s stupid to live in that unpleasant experience forever. The most painful situation took place long ago, but as you relive it you make yourself suffer over and over again. The main question is how much you want to break free of your patterns and dissatisfaction regarding what you’ve been through.

My teacher, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, helped me transform those unpleasant memories in such a way that I was able to look at and analyze them, see the positive aspects of the situation and get something better out of it. Then I was able to transform regret into understanding, and to realize that there’s really nothing to be sad about. What happened happened, yes, but what’s happened since then has been quite amazing. If I hadn’t had such a hard childhood, I may never have decided to become a nun. And if I hadn’t become a nun, I’m not so sure I’d have found a teacher as great as my teacher. And what I understood from him, from his love, nurtured me in such a way that I’ve learned to value the most meaningful things.

I hear what you’re saying, but many people in the West would have difficulty relating to that. People go through 25 years of psychotherapy and still don’t develop the kind of understanding that you’re talking about. I’d like to know how Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, in his practice of Buddhism, gave you tools to deal with and transform the pain. Well, one of the tools was that he gave me a space where I was totally loved. When I arrived at the Nagi Gompa nunnery at age 13, I thought I was in paradise. Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche really treated me like a child again. Before that I was never allowed to be a kid. Even if I spontaneously acted like one—like if I’d go out and play with other neighborhood kids—I was always expecting my father to come fetch me, to grab my hair and drag me home. I could never let go and enjoy myself.

In Nagi Gompa no one beat me up, although I was very naughty—you can ask the older nuns. Rinpoche always gave me a secure and safe environment. Those kinds of situations cleanse you; they give you a chance to transform without feeling like you’re in therapy—you’re simply growing up and developing.

My story is that of a simple girl who wanted to avoid suffering, just like everybody else. I looked for an alternative and was lucky to find a path that really allowed me to move forward. At times I spoke to Rinpoche about the fact that I wasn’t so happy about my dad, that I doubted whether or not he really was my father. And I certainly didn’t appreciate the way he treated my mother. Rinpoche helped me see the situation in a way that wasn’t quite so harsh. When he asked me if I thought my dad was violent because he hated me, I didn’t think so. He didn’t hate me; he was helpless.

What advice might you give people who have been victims of abuse? It is sad and unfortunate that those incidents took place. I don’t mean to say that it’s easy to deal with—it impacts your whole life. But what is needed is a spiritual environment where there’s a lot of love. Unconditional love makes us feel relaxed and accepted, without being judged. It allowed me to understand things in a simple way without blaming.

You’ve also said that giving to others the things you didn’t receive is a great healing process. Yes. The essence is being able to provide what the other person is lacking. I started by giving to my younger brothers: when I’d travel to Hong Kong or Singapore, I would always bring back some nice clothes or shoes for them. When I was a kid we basically never had such things. Shoes… I remember so clearly, just once there was a moment when I had no shoes. I’d had plastic shoes that got hard as stone in the winter and even those were gone. You know, when it’s that cold the skin slowly starts to crack and bleed. I know what it feels like when you don’t have what other kids of the same age and situation have, when you see classmates with nice new shoes, clean neat hair, clean neat dresses, new notebooks, geometry books, pencils, erasers… There’s always a question mark—why do they have those things and I don’t? Of course, I knew that the answer was that my parents weren’t as rich as the others. But you can’t help yearning. You’re a kid. You still want stuff you can’t have.

Yeah, even as adults! [laughs] Yes. So there’s always a hunger. When I grew up I still had that hunger in me, and I wanted to preserve my brothers from it. And now when I see other kids in similar situations, I immediately relate to them. Maybe I’m wrong, but I think I know what they’re going through, and my wish is to give what I didn’t get. Like when I go to Europe, I tell my friends, “You know people who have old plush toys, stuffed animals, children’s clothes. They don’t need them— give them to me.” I fill up an empty suitcase and bring them back, put them in my jeep, and then when I drive around and see some kids in the street playing in the dust with nothing at all, I just hand over some of these soft toys and teddy bears, and I see their faces and I really, really, really enjoy that so much. It’s like, ahhhh, I know what they’re feeling, and my satisfaction is even greater than their happiness. When people tell me, “Choying, you’re great, you’re doing such a wonderful job, you give so much to others,” I answer, “Technically, yes, it looks like I’m giving to them. But very honestly, I’m the one who’s enjoying it the most.” I’m addicted to it now—it’s a tickly feeling that makes you so happy!

Your special relationship with your teacher allowed you to forge strength out of the energy of anger, it seems. Yes, but in fact the methods he used could be applied to anyone. I mean, we really don’t enjoy those difficult experiences at all, and we know that they aren’t pleasant for anyone. But when you start to hate someone because of what happened, you suffer a lot more. The hatred itself will not make you happy. So who’s being affected by your hatred? The first person is you. I was so relieved when I began to understand my father, and see that he was a sick man who needed my help. Then I could try to help him and my mother; my wish was to see them happy.

My teacher used to tell me that repaying our parents’ kindness is one of the most important means of accumulating merit. As far as I’ve understood, we’ve been born so many times, had so many lives, it’s countless. During those countless rebirths we always had a mother and a father, and we can’t know if we’ve been able to repay their kindness or not, so we’re indebted to them.

You talk in your book about the freedom that you wouldn’t have experienced if you had chosen instead to marry and lead a family life. Any thoughts on monasticism? When many people are together there are always some problems because everyone isn’t enlightened, but being in a monastery is helpful because we’re all on the same path with the same goal, and that encourages us. In the West it would be preferable not to adopt the cultural side of monasticism, I think. In the Tibetan tradition there are so many stupid things that we follow without really understanding or analyzing them.

For instance, traditionally monks have had more chances than nuns to go for an academic education and become scholars. Only now is that changing—in certain monasteries here the rinpoches are really encouraging nuns to study. In the old days there was a Tibetan saying that went, “If you want a teacher, make your son a monk; if you want a servant, make your daughter a nun.”

In our culture we think girls should do all the housework, cooking, and cleaning. I don’t understand that. We’ve been brought up thinking, “Oh no! I can’t do that! I don’t know anything!” Why should guys’ work and girls’ work be different? “You’re a girl! You shouldn’t be doing that! Or saying that! Or wearing that!” It’s really strong here. Guys can help too, with laundry or taking care of children, for example.

Another thing is thinking that women don’t really need to pursue higher studies. In our school we now have sixty students—we started with seven! I remember once I was at a friend’s house talking to a khenpo, a scholar, and when I said I was going to found a school for nuns he very kindly said, “Oh, that’s wonderful, maybe I’ll come and teach.” I was so happy—I said, “Please do.” And the khenpo said, “Yes, maybe I will, because you know, it’s easy to teach nuns.” I asked, “Why?” And he said, “Well, because they don’t really need to learn much.”

We were talking about the deeply engrained bakchak, habitual tendencies, that lead to considering women and girls as unworthy of a lot of attention, and how the Tibetan language actually echoes this. One of the most common words for woman is kyemen, meaning “one of inferior birth.” I always used to have this argument with a monk. Monks don’t really mean to be cruel—I know that. But we’d be talking, and I used to be easy to provoke. “Inferior birth, kyewa menpa,” he’d say. “What are you? Such scummy things!” I’d get so pissed off! I’d say, “Where do you come from?” I’d use really impolite words: “You’re like a piece of shit that dropped out of a woman!” And they’d say, “Kyemen, you have obscuring energy, you’re tainted; we shouldn’t be sitting next to you. When wind that has touched you touches us we become defiled,” you know, just teasing me. And I’d answer, “If we have defilements, then you’re nothing but one big obscuration. You’re 100 percent obscuration.” Then I’d go to Rinpoche and cry, “Kyemen, bume, we’re dirty beings…”

Rinpoche would just laugh. “Oh, my dear, my dear,” he’d say, “Ask them if they know what the ma in lama or nyima is doing there? It is because ma is the very highest of qualities. Ma is woman, female, mother. It’s the feminine quality that is emphasized in every special thing, like nyima, the sun, giving warmth and light to the world. And pama, parents, who give you this precious life, nurture you, bring you up. And lama, the teacher. Those qualities are emphasized in special beings and special things. You know that in the practice of Vajrayana, women are very highly regarded!” Rinpoche used to encourage me, and I’d feel better and leave thinking, “Yes, we are special!” [laughs]

How do you explain this situation? Well, in addition to the ignorant assumption that women have less potential than men, in our culture humbleness is considered a great quality. They say: Be humble, don’t be bold or brazen. But sometimes this practice of humility becomes stupid, and then it discourages us and keeps us from recognizing our own potential. Everyone has potential; a good teacher or education can help us use it to benefit beings in whatever we do. I really wish to see all women educated, both intellectually and spiritually. An intellectual education helps you be smart and do things more skillfully. But what you’re doing intelligently may not really be meaningful, right? A spiritual education helps you do things more wisely and meaningfully.

Is humbleness just for women? No, no—in general, of course, we believe that you shouldn’t be arrogant; in the absence of arrogance is humbleness. How I understand it is, of course you have to be humble, but not totally ignorant. Not blind. It’s like you have to be compassionate, but wisely compassionate. With stupid compassion there’s a lack of balance that can lead to undesirable consequences like frustration. We should really understand what compassion is. Then when we try to implement it, there’s no danger.

What’s your understanding of wise compassion? Well, it’s respect. I’m not a learned person, but what I’ve understood from my teachers is that just as you really don’t wish for yourself any sorrow or pain, everyone else has the right to be happy too. You try to respect that for others, but not as pity. If you try to help a person, you try it genuinely, sincerely, from your heart. How much you can help is another question, but you want to help, you want to try.

Here’s an example. In Kathmandu there’s this crazy traffic, and you never know how long you’ll be stuck in it. It’s irritating at times, but I try not to be irritated, because it’s not going to help me. So sometimes when I’m driving I listen to music, I hum or sing, or I just look around at people walking. Maybe I see a woman dragging her kids along and looking really sad, and I end up praying for her—I pray that her husband treats her well, makes her happy, and helps her in her work. And those vendor guys who carry fruit and vegetables on their bicycles—it’s so hot, and they’re working so hard. I look at them and wish that they’ll sell all of their stuff, make a good profit and go home to their family with a big smile and have a good meal. It’s a wish for short-term happiness. Of course overall, whenever I make wishing prayers in a puja or walking around the stupa, the prayer is always, “May all sentient beings be free from suffering. May they be able to understand dharma.” But then I see some young girls trying to be so pretty, they’re so conscious about their appearance, and I just know they’re looking for boyfriends. And I pray that they’ll get good boyfriends. Or some old guys who obviously have difficulties walking because of their big bellies, and I think, “May they find it easy to lose weight so they can get around more easily.” It makes me happy to fill my mind with these thoughts.

In Nepal you’re known as the “singing nun.” Why do you sing? Since childhood it’s been my nature to thoroughly enjoy singing and dancing; even in Nagi Gompa I’d be the entertainer for Tibetan New Year and other festivals—I was always the first one to jump out and dance and sing for everyone. But the credit should go to [American musician] Steve Tibbetts, who had the idea to make the first album that presented me to the world as a singer—before that it wasn’t really my goal. And now I enjoy it so much because it makes people happy. And it generates income and gives me the financial freedom to do what I want to do, to run the school and plan other projects.

Your song “Phool Ko Aankha Ma,” (“In the Eyes of a Flower”), from the 2004 album Moments of Bliss, was in the Nepali Top Ten for a year and won several prestigious awards. What’s it about? The song says, “In the eyes of a flower, the world appears as a flower; in the eyes of a thorn, the world appears as a thorn. Shadow or reflection takes place according to the shape of the object.” So basically it’s saying how everything depends on how we perceive things in our life. Negativity has a negative effect; positivity has a positive effect. According to an individual’s way of understanding, judgment takes place.

The most beautiful part of the song says, “May my heart always be pure, may my words always be enlightened, may the soles of my feet never kill an insect. In beautiful eyes, the world appears as beautiful.” The second part says, “May I see the brightness of moon in the darkness of night. May I hear the music of life even in the driest leaves. In a pure heart, the world appears as pure.” Those are the lyrics: pure conception, pure vision, pure motivation, pure thoughts. Usually we think only of the darkness of night, but instead of seeing the darkness, may I see the brightness of the moon. It’s the same for the sound of dry leaves that are blown about in the wind—nobody thinks of this as music, but with pure perception it is taken as music and enjoyed. The whole song is about how to develop positive attitude. I’m not saying anything new—the text comes from the Buddha’s teachings, from the Dhammapada. I feel this is the most beautiful prayer. And I’m really happy that people in Nepal, even small kids and very important people, are humming this prayer.

That song has certainly touched a lot of hearts. Yes, there was a time when it was almost like an anthem for everyone. Even political people would be having a discussion or disagreement, and one of them would say, “Oh, you know, it’s like the song—in the eyes of a flower…” The other day I was joking with my friends and they asked me what my New Year’s wish was. I told them it’s to hear the Prime Minister of Nepal sing, “May my heart always be pure, may my words always be blessed, and may my feet never kill an insect.” [laughs]

What do you consider your greatest achievement? Well, I still have a long way to go, you know? But so far I’m really happy with what I’m doing and the way it’s taking place. I’ve just started.

♦

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.