The life story of the Buddha is one of the central teaching tales in all Buddhist traditions. It is an inspirational story that is meant as a model for all people: a man turns his back on the pleasures and sufferings of human society, sets off on a rigorous path of practice and reflection, attains a state of freedom from suffering, and then teaches the theory and method of his accomplishment to others. Tibetans, who have produced what is possibly the largest collection of sacred literature in the world, adapted the format of the Buddha’s quest for enlightenment to the telling of the life stories of their own religious masters. These biographical works are known in Tibetan as namtar, which literally means “enlightenment.” The Tibetans have produced a dizzying number of them.

Since its launch three years ago, the Treasury of Lives, an online encyclopedia, has been mining the rich tradition of Tibetan biographical literature to publish, in English, biographies of men and women, both Buddhist and Bön, from Tibet, the Himalayas, and Inner Asia. The goal of the project is to have a clear, reliable biography of every religious figure whose life and deeds were recorded—every lineage holder, teacher, abbot, incarnation, hermit, wandering ascetic, village lama, magician—and also of the laypeople who supported or were otherwise involved in the religions. In short, a biography for everyone whose name is known.

In these biographies one finds both the famous and the obscure, both those who established monasteries and teaching traditions, and those about whom nothing more is known than that they were the student of one person and the teacher of another—a simple name in a long chain of transmission.

It is that chain of transmission—from master to disciple, from one incarnation to another, or from one abbot to his or her successor—that gives Himalayan Buddhism much of its historical character. Lineage matters in Buddhism. Tibetans write biographies not just to inspire but also to legitimate the teaching of their masters by linking them to the great men and women of the past, and ultimately to the Buddha himself.

Incarnation lineages also seek to accomplish this linkage, but do so in a far more complicated way. They are perhaps best thought of as an art rather than a historical exercise. They often involve pre-incarnation lists that stretch back into mythology and sometimes involve so many figures that the list is more of a Who’s Who of Tibetan history. More than one reincarnation of a single person are often identified, and when lines split in this way the multiple incarnations might find themselves in the odd situation of teaching to or learning from each other.

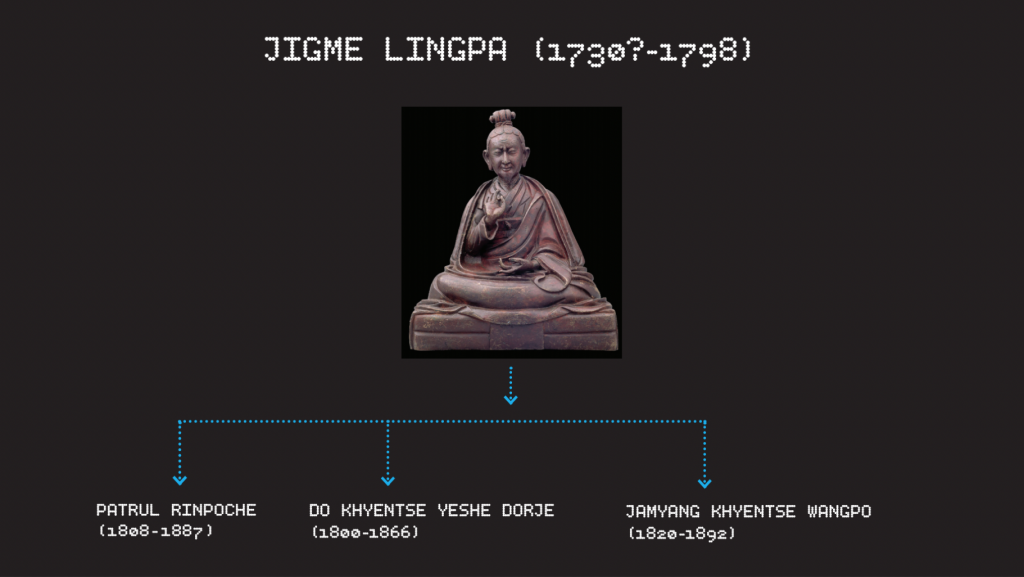

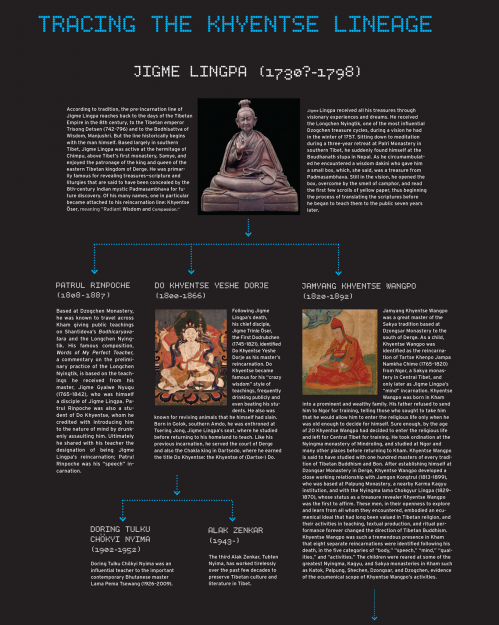

Take the remarkably complex incarnation line that stemmed from Jigme Lingpa (1730?–1798, see opposite page), the eccentric master who is credited with the revelation of one of the most famous Nyingma practice liturgies, the Longchen Nyingtik. The wild popularity of the Longchen Nyingtik seems to have incited its promoters to repeatedly insist that Jigme Lingpa’s presence was ongoing, literally embodied in the tradition’s lineage holders. Three reincarnations of Jigme Lingpa were identified, and one of them, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820–1892), had eight recognized incarnations; to date there have been dozens of men who are said to be rebirths of the great Jigme Lingpa, categorized as the incarnations of “body,” “speech,” “mind,” “activities,” or “qualities.” Many of these teachers who are members of this incarnation stream have been active in the propagation of Buddhism outside of Tibet, including Dilgo Khyentse, Dzongsar Khyentse, Beru Khyentse, Jigme Khyentse, and Alak Zenkar. Over the last 200 years, countless men and women have sat at the feet of Jigme Lingpa’s numerous reincarnations and learned from them.

Tibetan incarnation lines are not all this complicated—they do not always split into multiple streams, or reach back into early history and mythological time for pre-incarnations. Most start simply with the reincarnation of an influential master and proceed forward as each incarnation passes away and a new child is found and trained. In the case of Jigme Lingpa, and later Khyentse Wangpo, the impact of their lives were so widely felt that one reincarnation was not sufficient to maintain it. Multiple groups who continued the transmission of the teaching held up their masters as living embodiments of the teacher, and multiple centers of Longchen Nyingtik practice sought to host incarnations to further the tradition.

In reflecting on the legacy of Jigme Lingpa, we are left with the thoughts that Buddhism in eastern Tibet in the 19th and early 20th centuries was fluid, vibrant, and interconnected. This is a legacy that holders of the tradition continue to embody. The men belonging to the Jigme Lingpa/Khyentse incarnation lines have made immense contributions to the vitality and preservation of each and every school of Tibetan Buddhism. Their extended biographies, available on the Treasury of Lives website, are full of details of their vast learning, unwavering dedication, and accomplishments in both teachings and practice.

Click here to view Tracing the Khyentse Lineage, a visual chart of the Khyentse line.

♦

[Correction: It is written that no details are known about Jamyang Chokyi Wangchuk, but the author has since learned that he was the uncle of Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, a Dzogchen master based in Italy. Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche has published a biography of his uncle, The Lamp That Enlightens Narrow Minds (Shang Shung Publications, 2012), detailing the activity of this important master. Tricycle and the author regret the omission of this information.]

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.