According to the calendar spring is just 10 days away, but winter still has its icy grip on Montreal, Canada. Wearing an oversized parka and a borrowed pair of boots, Kazuaki Tanahashi carefully picks his way down a slush-encrusted sidewalk while I hover protectively, worried that he will lose his footing. “I’m all right,” he insists, but I’ll have some explaining to do if something happens to a national treasure on my watch.

Moments earlier we were deposited on Boulevard Saint-Laurent by a cab driver who had been unable to find the address we were looking for. After backtracking several long blocks in a cold, beating rain, we finally arrive at the venue for the evening’s poetry readings. Despite the weather, Kazuaki-san is none the worse for wear. In fact, he appears positively serene as he listens to the poets. It’s a look I will see often throughout the four days we spend together at the Montreal Zen Poetry Festival.

Kaz (as everyone calls him) has been invited to Canada to conduct calligraphy workshops and deliver a talk on the Japanese poet Ryokan. Each morning he joins other festival participants for zazen at Enpuku-ji, the Zen center sponsoring the poetry festival, and pitches in with the cooking and cleaning. At the age of 77, this is more or less how he occupies half of each year, traveling from his home in Berkeley to teach at Zen centers, colleges, and art schools throughout the North America and Europe.

“I enjoy teaching calligraphy and brushwork,” he says in his quiet voice. Even though he has watched thousands of people struggling to copy brushstrokes from classical examples, teaching is always a fresh experience. “Each time I learn something,” he says. “I feel like I’m becoming a better calligrapher.”

In the guise of wandering artist, Kaz has become a beloved figure in American Zen circles, counting many prominent dharma teachers and students among his friends. But Kaz has arguably made an even more important contribution to Western Zen through his 50-year project of translating Eihei Dogen, the 13th-century Buddhist teacher who brought Soto Zen from China to Japan and gave written expression to his insight in a dense, sprawling text called Shobogenzo, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye.

Kaz spent much of the 1960s translating the Shobogenzo into modern Japanese, for the first time making Dogen accessible to more than a handful of scholars and Soto priests. Since 1977 he has worked with a team of American collaborators—poets and Zen teachers, mainly—to translate the Shobogenzo into English. This year Shambhala Publications released the complete work in a two-volume 1,280-page edition.

“He was able to take on Dogen and work with many, many voices and always hold those twin poles of source and originality,” says his friend, poet and Zen teacher Peter Levitt. “I think it’s really key to his character.”

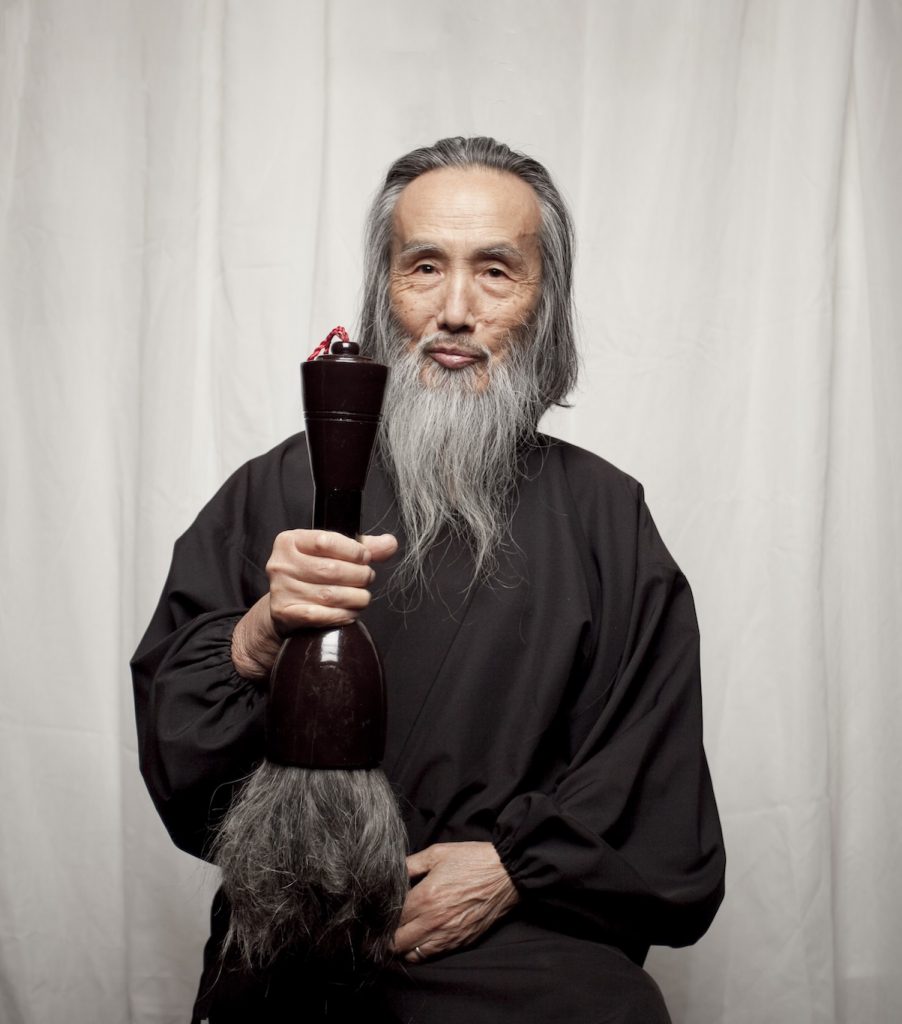

With his shoulder-length hair, long gray beard, and deep-set eyes, Kaz faintly resembles an ancient hermit (albeit one who wears running shoes and uses a laptop). He appears comfortable with stillness, willing to let silence be without needing to fill it. But things are not always as they seem. Just a few weeks before the poetry festival, I’d met him for the first time at Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and had driven him to the Albuquerque airport. At one point during the hour-long trip he shot me a sidelong glance and said: “I’m a lot crazier than you think.” When we sat down for a series of long conversations in Montreal, I realized he wasn’t kidding. Kaz has spent a lifetime coloring outside the lines, defying Japanese cultural conventions to pursue his own vision as an artist and activist.

Kaz was born the elder son of a staff officer in the Japanese army who in the years leading up to World War II lobbied behind the scenes to keep his country from going to war with the United States. A Shintoist, his father studied with Morihei Ueshiba, the revered founder of the Japanese martial art of aikido, and sought Ueshiba’s counsel in trying to avert the coming disaster.

Kaz was born the elder son of a staff officer in the Japanese army who in the years leading up to World War II lobbied behind the scenes to keep his country from going to war with the United States. A Shintoist, his father studied with Morihei Ueshiba, the revered founder of the Japanese martial art of aikido, and sought Ueshiba’s counsel in trying to avert the coming disaster.

After the war, when American occupiers briefly banned the teaching of martial arts, Ueshiba retired to the countryside to farm. Kaz and several friends who lived nearby studied with the master for a year and a half. The young teenagers were the world’s only aikido students at the time. From him they learned that “the secret of martial arts is love,” Kaz says.

“I was the most clumsy student of the great master,” Kaz says. “But I learned a lot, and also I think the master entrusted each one of us, saying, ‘You take care of aikido.’” Indeed, Kaz’s first feat of English translation was a book about aikido written by Ueshiba’s son.

Like many Japanese in the war’s aftermath, Kaz’s family was impoverished. Dropping out of high school, he took a job as a printer’s apprentice in Tokyo. He tried enrolling at a university, but found it boring and quit. “My father was very authoritarian,” he says. “In a way, I went just the other way.”

By the mid-1950s, Kaz was practicing English in Bible classes conducted by an American missionary named Elizabeth Buchanan, who suggested that he practice calligraphy to improve his atrocious handwriting. He was also studying Western art and reading the Existentialists.

“I thought, ‘To be a good artist you have to be in despair or be bored,’” he recalls. “I don’t like to [be those things], so I was looking for something else. Then I found Dogen. Dogen was so positive and profound. I didn’t understand, but I could feel there was some kind of vast field there.”

Dogen wrote in Japanese (rather than classical Chinese) in a compact, unconventional style that expressed the depths of his Zen insight. Solving the puzzle of Dogen’s prose was part of the attraction, Kaz recalls, and “to decode his thinking, which is utterly positive, utterly beautiful, was a real pleasure.”

Kaz mounted his first art show in 1960 with calligraphic painting based on one of Dogen’s poems. He befriended an elderly visitor named Shoichi Nakamura, a Soto Zen priest who had studied Dogen in the original medieval Japanese. Nakamura agreed with Kaz that Dogen needed to reach a wider contemporary audience. “He and I started sitting once a week all afternoon and then trying to translate the Shobogenzointo modern Japanese,” Kaz recalls. “It took us maybe one afternoon to work on one sentence.”

In 1964, Kaz embarked on an 18-month tour of North America—his first—traveling by bus across the continent to meet gallery owners and aikido teachers. In San Francisco he dropped in on Shunryu Suzuki, a Soto priest who had some Westerners sitting in his zendo. Suzuki used a translation of the Hekiganroku(The Blue Cliff Record), a Rinzai Zen koan collection, with his students because he thought Dogen was too difficult for Americans.

“I said, ‘Here you are, teaching foreign students. Don’t you think Dogen is the best?’” Kaz recalls, “There was kind of a dead silence for some time. And Suzuki Roshi said, ‘Well, I’m scheduled to give a talk to my students next Sunday. Will you talk about Dogen for me?’”

Kaz complied. “Perhaps my talk was the very first public presentation of Dogen in North America,” he says. Today, more than 50 books about Dogen have been published here.

In Hawaii, Kaz met Robert Aitken—not yet a roshi—with whom he translated a portion of the Shobogenzo called Genjokoan (Actualizing the Fundamental Point). The collaboration with Aitken became the first of many Kaz would undertake with Western Zen teachers.

Back in Japan, Kaz and Nakamura completed their four-volume modern Japanese translation of the Shobogenzo in 1968; Kaz spent the next few years researching a book on Enku, a 17th-century wood sculptor, while considering a return to the U.S.

In 1977, Kaz moved to San Francisco Zen Center at the invitation of Suzuki Roshi’s successor, Richard Baker Roshi, to serve as a scholar-in-residence. “I like American people and speaking in English and writing in English,” Kaz says by way of explanation. “American society is more free. Artists can do anything they want. I wanted to do that.” At first he spent his time translating dharma transmission documents, but one day the head cook, Arnold Kotler, approached him with three different translations of Dogen’s Tenzo Kyokun (Instructions for the Cook). “I tried to help him, but I thought it would be easier to translate right from the original,” Kaz says. “So we did that, and then we started translating other things.”

In 1977, Kaz moved to San Francisco Zen Center at the invitation of Suzuki Roshi’s successor, Richard Baker Roshi, to serve as a scholar-in-residence. “I like American people and speaking in English and writing in English,” Kaz says by way of explanation. “American society is more free. Artists can do anything they want. I wanted to do that.” At first he spent his time translating dharma transmission documents, but one day the head cook, Arnold Kotler, approached him with three different translations of Dogen’s Tenzo Kyokun (Instructions for the Cook). “I tried to help him, but I thought it would be easier to translate right from the original,” Kaz says. “So we did that, and then we started translating other things.”

Kaz would eventually translate 96 Shobogenzo fascicles (chapters) with the help of a group that reads like aWho’s Who of American Zen practitioners: Kotler, Aitken, Sojun Mel Weitsman, Zoketsu Norman Fischer, Dan Welch, Taigen Dan Leighton, and many others. In 1985, the first collection of newly translated fascicles was published as Moon in a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dogen.

Meanwhile, Kaz had fallen in love with and married Linda Hess, a Zen Center student who is now a senior lecturer specializing in 15th- and 16th-century Hindu poets at Stanford University; they had two children, Karuna and Ko. As the translation work progressed, Kaz realized that the book might never have an audience, “There might be a nuclear war—living in San Francisco, we are a target.” And now that he had a family, he had skin in the game.

This realization marked the start of Kaz’s political activism, a path that has included organized opposition to the Gulf and Iraq wars, pushing for nuclear weapons bans and establishing A World Without Armies, a nonprofit dedicated to global disarmament. In the early 1990s he joined with the painter Mayumi Oda and other Japanese expatriates in a successful campaign to block the importation of plutonium into Japan for a dangerous nuclear reactor project.

“In aikido you have a partner who’s much bigger and stronger than you, and you get thrown down,” Kaz explains. “You have a chance to throw down the big guy, too. So it’s a continuous being- thrown-down and then throwing down. It’s like the situation with plutonium. We tried many things and we failed. Once in a while we win, too.”

While taking part in public vigils, Kaz also expressed his concerns through his art, which he resumed showing in 1980 after a 15-year hiatus, creating giant multi-hued “one-stroke” brush paintings on various unconventional media. Soon he was incorporating other elements, like pasting his infant son’s wadded- up shirt to the canvas. “It was kind of showing the end of the world—even a baby is dead,” he says. “A disturbing image.”

All the while, the translation project continued. Peter Levitt, who served as associate editor of the Shobogenzo project, first met Kaz at a conference of Buddhist artists sponsored by Thich Nhat Hanh in 1987. Thay (as Thich Nhat Hanh is called) asked Kaz, Levitt, and the late Rick Fields to produce a new translation of the Heart Sutra. “We spent two or three hours trying to translate the word dukkha, and we couldn’t agree on what suffering was,” Levitt remembers. “We couldn’t figure out how you say, ‘Life is not so good.’”

After insisting that Levitt should be the one to break the bad news to Thay, “Kaz said to me, ‘So your dukkha is more than mine right now,’” Levitt recalls, laughing. “I said to him, ‘If only I could describe what I’m feeling!’”

The two became friends and worked together on translating Dogen. “He wanted to have a translation that sounded as if Dogen was teaching in English,” Levitt says. Levitt’s main job was to ensure the consistency of the various translations. The pair often labored to find the English word that correctly conveyed the nuances of a technical term in medieval Japanese. Kaz’s lifetime of Dogen study was of tremendous benefit, Levitt says. “There’s no question in my mind that if we had done this when Kaz was 30, instead of 70, we would have a very different Shobogenzo,” he says.

Setsuan Gaelyn Godwin, abiding teacher at the Houston Zen Center, got to know Kaz while training at San Francisco Zen Center and Tassajara Zen Mountain Center and teamed up with him to translate one of the Shobogenzo fascicles. “He never isolated himself with the idea he should do it alone,” she says. “He had the wisdom that it should be influenced by actual Zen people in the West, which is so generous.”

Godwin marvels at Kaz’s stamina during his annual calligraphy workshops for her sangha. “He’s in it for the long haul,” she says. “He’s got this strong, energetic quality that still seems calm. People flock to see him. He’s an example of being creative in a non-wild way.”

In Montreal, samples of Kaz’s brushwork have been hung around the memorial chapel being used for the poetry performances, and Kaz offers a calligraphy demonstration for audience members and the other guests. This year, Enpuku-ji abbess Zengetsu Myokyo Judith McLean has invited acclaimed poets Jane Hirshfield and Robert Bringhurst, as well as Dogen scholar Steven Heine and others, to participate in the poetry festival.

Jion Ned Shepard, an Enpuku-ji monk who has helped to organize the poetry festival, tells me that while he was helping Kaz hang his paintings, he asked how long Kaz had been doing calligraphy.

“He told me, ‘Seventeen hundred years,’” Shepard says. “Thinking he had misunderstood my question, I said, ‘Yes, but how long have you been doing calligraphy?’ ‘Seventeen hundred years—collective “you.’””

Eighty people watch as Kaz, wearing traditional samue (a monk’s work clothing) and kneeling formally in seiza, dips a wooden-handled brush into a bowlful of black sumi ink, gracefully tracing out the character for kokuro. “This means ‘heart’ or ‘mind,’” he tells them. Next comes a one-liner: “Some people say, ‘Why do you have one symbol for two things?’ And I say, ‘Why do you have two words for one thing?’”

Kaz offers to take requests. Someone calls out, “Peace,” and he draws the character with quiet assurance. “We don’t have to fight,” he murmurs. “Our children do not have to fight. Everyone’s wish.”

“Spring,” someone else suggests.

“Spring,” he repeats. “Oh, you need it. I came from Berkeley. Cherry blossoms were already over when I left.”

Back at Enpuku-ji, I ask Kaz what he thinks Dogen—whom he refers to as his “remote teacher”—was thinking as he obsessively wrote and rewrote portions of the Shobogenzo.

“What he was trying to do was be as authentic as possible, getting closer and closer to the original teachers’ teachings,” he tells me. “He knew it was kind of impossible to convey his understanding, because most of his students were not following him.”

Dogen had no publisher, so only a few followers read what he had written during his lifetime, Kaz says. “Maybe he foresaw that his writing would be forgotten for a long time, but he could not help pursuing this writing and taking it deeper and deeper.”

I point out that he has been reading and translating Dogen for about as long as Dogen was alive.

“We are constantly in conversation, and in a way we are helping each other,” Kaz says. “Of course, he helps me how to think, but also I help him to think in a Western way, how to think in English. We are helping each other.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.