Monuments and their visual representations have come to define our collective identity—think the Eiffel Tower in Paris or the Statue of Liberty in New York City.

A new exhibition at the Rubin Museum of Art invites you to explore Lhasa, Tibet’s sacred and political center, through more than 50 works of art that show rare images of central Tibetan villages and landmarks from before the mid-20th century. These images of iconic architectural sites were created by both Tibetan and Western artists.

Located at an important axis of trade and pilgrimage routes, Lhasa has attracted Buddhists, merchants, and other travelers since the seventh century. Its temples, monasteries, and palace-fortresses were the focal point and goal of these journeys—they provided halting points along the route, acted as commercial hubs, and housed sacred Buddhist images and religious personages. Visitors have been diverse: Mongolian, ethnic Buryat and Kalmyk Russians, Nepalese, Bhutanese, Indian, Chinese, and other Himalayan people, Muslim traders, European Christian missionaries, Japanese, European and American diplomatic officials, and explorers. Lhasa, which was the ancestral home of the Dalai Lamas until the 1959 Tibetan uprising, continues to draw visitors from different parts of the world to the present day.

As “Monumental Lhasa: Fortress, Palace, Temple‘s” curator, Natasha Kimmet, will tell you, architecture is an intrinsic part of our daily lives, conditioning how we experience places and interact with people. Because some buildings have become iconic symbols of places, these buildings resonate with us, even if we know them only from images.

“We constantly seek to capture moments in images that we filter and edit to share in various ways, especially online and via social media. In this way, buildings have a life that extends well beyond the material structure itself,” Kimmet said.

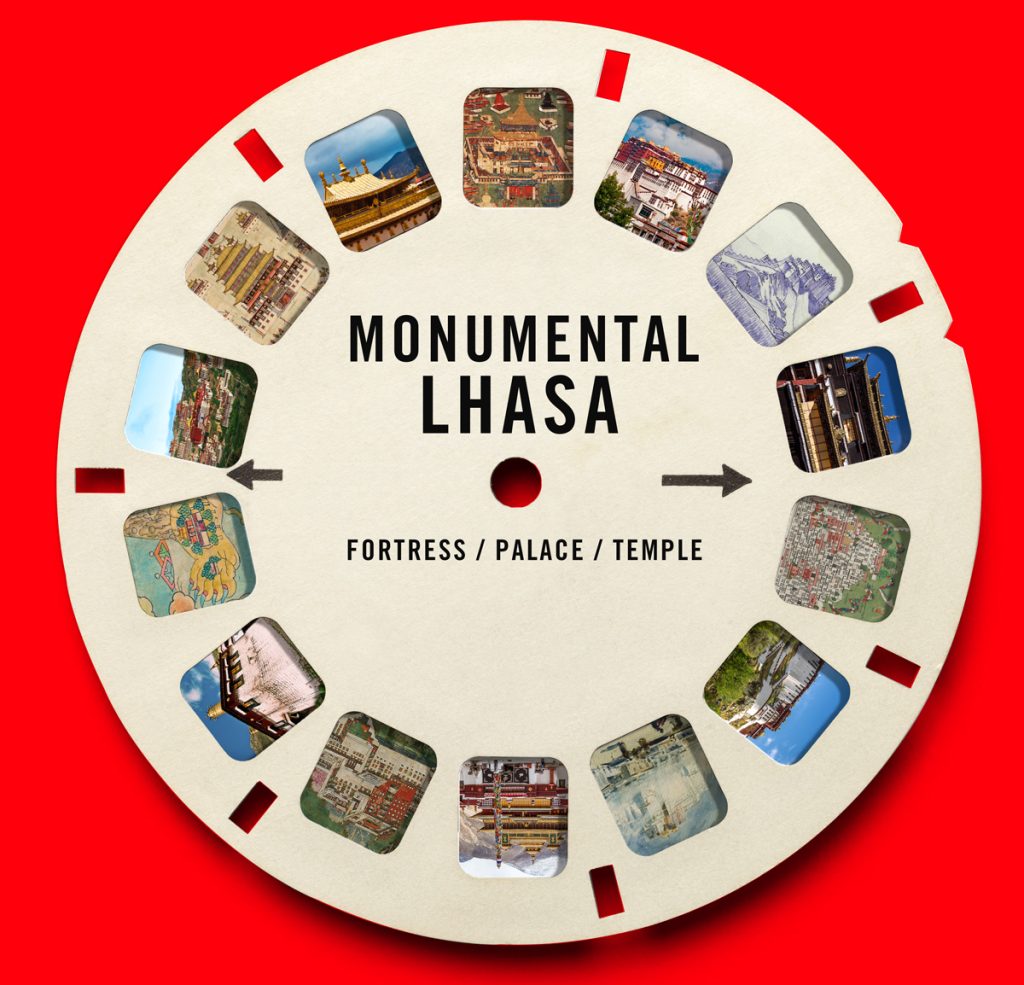

The exhibition also has interactive elements, including a digital photo album and View-Masters, to provide opportunities to more deeply engage with the monuments and their visual representations.

When asked whether the Rubin hopes that displaced Tibetans who can’t visit their homeland will come and experience the art, Kimmet said that while this exhibition will appeal to a Tibetan audience—and a Buddhist audience more broadly—it will also do so to anyone interested in travel, architecture, and the cultural significance of monuments.

“While many of the works in the exhibition were created by Buddhists, ‘Monumental Lhasa’ also examines images created by Western explorers, military officials, and scholars who did not have ancestral connections to Lhasa but instead had personal, political, and other motivations for visiting the city and recording its sites,” said Kimmet, adding that the works come together to illustrate how Lhasa has held significance for many different groups of people.

While the Tibetan images in the exhibition are shaped by Buddhist religious and historical narratives, the ones by Western and other foreign visitors depict imperial exploration, travel, and scientific discovery, highlighting how architectural images have often been manipulated to convey the messages of patrons and artists. Tibetans and foreigners frequently adjusted their representations of Lhasa’s buildings and geography to convey specific motives or perspectives—a practice that continues today through the use of photo editing tools like Photoshop and filters and apps for social media.

One example is “Tashilhunpo Monastery,” painted by an unknown Tibetan monk and commissioned in the 19th century by Major William Edmund Hay, the former assistant commissioner of the Kullu region in present-day northwestIndia. While it is similar to other Tibetan architectural paintings in terms of the composition and how the monuments are presented, the piece also demonstrates the motivations of the British patron by focusing on travel routes and mapping the territories of Tibet that the British were not permitted to access.

Another highlight from the exhibition is “Drepung Monastery,” which has been part of the Rubin’s permanent collection since 2006. Drepung is where the Dalai Lamas and the Ganden Phondrang [the Tibetan government established by the fifth Dalai Lama] previously lived, and the monastic town was once home to as many as 8,000 Buddhist monks.

The painting shows Drepung as a sacred Buddhist paradise or “pure land,” with the town set among rolling hills, flowers and animals, stylized rocks, and a schematic formation of cloud-topped mountains. There are pilgrims traveling across the hills and monks engaged in daily activities throughout the monastery.

By collectively displaying these images, the Rubin takes viewers to the key sites of central Tibet and show them how architecture, geography, and the identity of Tibet have been represented. Which is why these paintings, photographs, and other artwork were created in the first place.

“Monumental Lhasa” runs through Jan. 19, 2017 at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.