Buddhist practice and Buddhist art have been inseparable in the Himalayas ever since Buddhism arrived in the region in the eighth century. But for the casual observer, it can be difficult to make sense of the complex iconography. Not to worry—Himalayan art scholar Jeff Watt is here to help. In this “Himalayan Buddhist Art 101” series, Jeff is making sense of this rich artistic tradition by presenting weekly images from the Himalayan Art Resources archives and explaining their roles in the Buddhist tradition.

Controversial Art, Part 2: The Svastika

In the Western world, the svastika has come to represent the evil of the Nazis of World War II. But the word itself—written “swastika” in English—means “auspicious” in Sanskrit. In the Tibetan Zhangzhung language, it is referred to as yungdrung, meaning “everlasting.” Most languages, in fact, have their own variation on the millennia-old, cross-cultural symbol of the svastika.

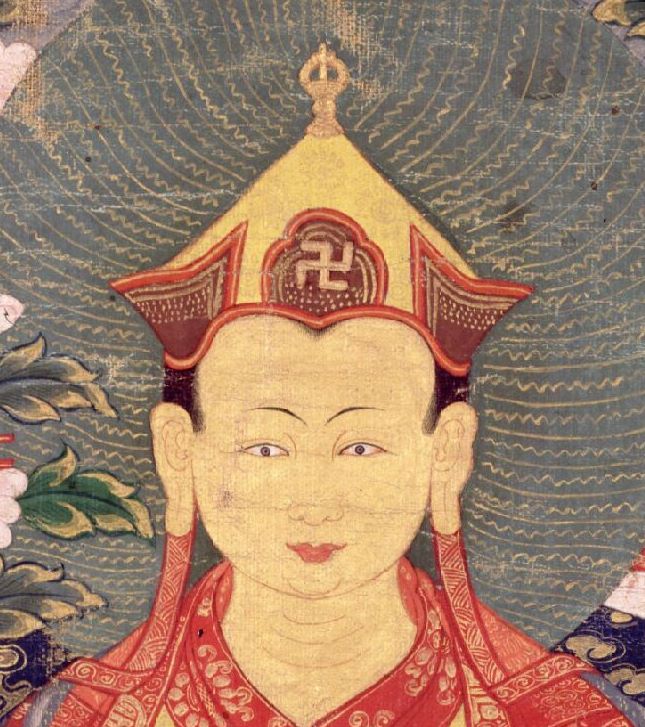

In the Buddhism of the Himalayas, Tibet, and Mongolia, the svastika is a ubiquitous symbol used primarily as a decorative element. Common in woodcarving and architectural relief, the symbol taken on its own offers auspicious and stabilizing qualities.

In China, it is common to find a svastika outlined over the heart of a Buddha figure in painting and sculpture. The symbol can even be included in the double-vajra textile motif found on the front of the thrones of important Buddhist teachers such as the Dalai Lama. The svastika is very rarely found in Buddhist ritual practice and, in such cases, is more closely associated with yantra diagrams and magical devices for warding off thieves and protecting wealth.

In general, Buddhism is not overly concerned with the direction the svastika turns. This is not true for the Bon religion, however, where the left-turning yungdrung is the principal symbol of the religion, and a right-turning yungdrung has no meaning. The word is also part of the official name of the religion, Yungdrung Bon—”Everlasting Truth.”

The yungdrung is also commonly found in the hands of Bon teachers and deities in a variety of shapes, colors, and sizes. It is even used for religious hats and seats, carpets, and for marking the bottom of Bon sculpture. Since ancient times, the yungdrung has been one of the more common etchings in pictographs and petroglyphs of the western Himalayas and Tibet.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the svastika was used on modern European maps to differentiate between Bon and Buddhist monasteries: the Bon locations were marked with a left-turning svastika, and the Buddhist ones were marked with a right-turning svastika.

A common mistake made in identifying the svastika in Himalayan art is mistaking the bliss whorl used in Tantric imagery for a svastika. The bliss whorl is a spiral-shaped circle with three to four legs—and occasionally two—that is envisioned as a flat disc-like shape.

Despite the confusion surrounding the symbol of the svastika, it remains, due to its almost endless uses, a fixture in Himalayan art, religion, and culture.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.