On Wednesday of last week I woke up in the predawn darkness, the vestiges of jet lag from a month in Sri Lanka still washing over me. I reached for my phone and was immediately greeted by the news that several staff members of Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical magazine, had been killed by Islamic fundamentalists. Twelve people in all were confirmed dead. The news had me reeling. What does it mean to live in a world where blood is still shed over medieval debates about what is blasphemy and what is not? And yet I have to say that the enemy of free expression, of everything that is sacred to me as a writer, is not Islam but fundamentalism of any kind. I know this because I am from Sri Lanka and Sri Lanka has the dubious honor of birthing Fundamentalist Buddhism.

On Sunday June 15, 2014, in Sri Lanka, the land of my birth and a country I feel deeply tied to by both love and despair, the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS) went on the warpath. In English, “Bodu Bala Sena” translates as the “Buddha Power Force,” a puzzlingly oxymoronic label for a militant faction of Buddhist monks dead set on defending the country, by any means necessary, from what they see as encroachment from Muslims and Christians.

Sri Lanka is a country of deep devotions. Almost every street in the capital, Colombo, boasts churches, mosques, and temples—often in close proximity. Lonely country crossroads shelter shrines to Ganesh or St. Sebastian. But the most ubiquitous religious icons are the Buddha statues that dot the country, from tiny garden shrines to 80-foot-tall figures rising up from the forest in the ancient Buddhist citadels of Polonaruwa and Anuradhapura. For much of the country’s history—despite a 26-year-long ethnic civil war—the religions have generally coexisted.

Yet in recent times a brand of militant nationalist Buddhism led by BBS has risen to prominence in part as a response to what monks see as the unchecked spread of Islam and the economic strength of the Muslim community. These monks have assumed the mantle of defending Sinhala Buddhism, the racial and religious strain of Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka that has existed on the island since ancient times, and they have grown stronger and more vociferous with time.

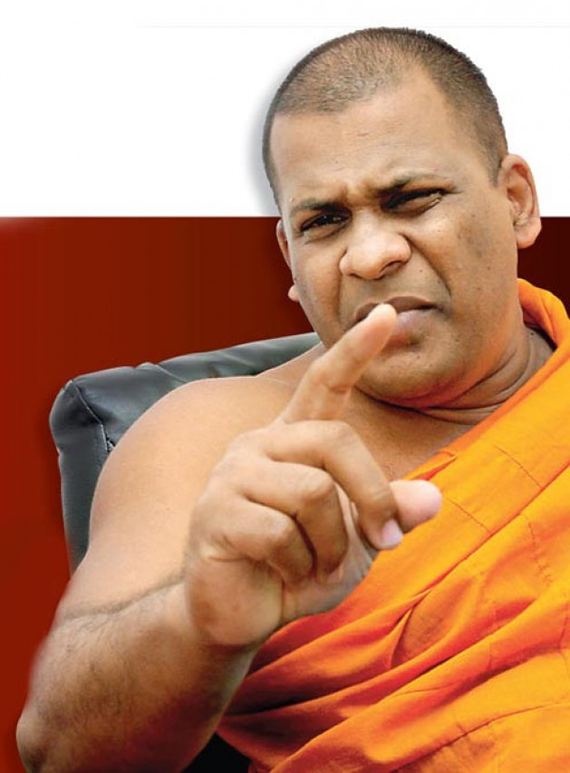

June 15, 2014, however, marked a new demonstration of the power of BBS. The monks gathered in a town called Aluthgama. Their leader, Gnanasara Thera, was delivering a hate-filled speech warning Muslims that they lived in a Buddhist country. “In this country we still have a Sinhala police force; we still have a Sinhala army,” he declared. After today if a single Marakkalaya [derogatory term for Muslims] or some other paraya [derogatory term for alien] touches a single Sinhalese . . . it will be their end.” A crowd of 7,000 gathered to see the strange sight of an orange-robed monk shouting racial epithets and threatening violence. That night, after the speech, inflamed Sinhala mobs roamed the streets setting fire to buildings, harassing and attacking Muslims. By the end of the day, there were three confirmed deaths, 78 injured persons, numerous businesses and homes destroyed.

I called Muslim friends in the country; they were all safe but afraid. “Being a minority in Sri Lanka is like being in an abusive marriage. We never know when we are going to get whacked!” said one on her Facebook page.

As a Sinhala Buddhist myself, watching the riots in Aluthgama has been a heartbreaking experience of profound cognitive dissonance. The Buddhism I was taught as a child stressed love and compassion. Buddhism now joins Christianity and Islam in a disturbing trend toward fundamentalism and exclusion. And like moderate Christians and Muslims, moderate Buddhists must now attempt to present a reasoned counterweight to these reactionary religious tendencies.

These riots also made me confront something I’ve never felt before: the despair of Muslims who strive to be both faithful to their deeply held sacred beliefs and distant from dangerous fundamentalist ideas. For the first time I felt what it was to be lumped in with dangerous people who would kill in the name of our supposedly shared beliefs. What does it mean to call oneself a Buddhist when these are the actions committed in the name of Buddhism? I’m sure this is a question that Muslims are faced with constantly, as they are caught in the vice between Islamic fundamentalism and international anti-Muslim fervor. The day after the Charlie Hebdo attack, a Muslim friend reacting to the push for Muslims to separate themselves from the attacks wrote, “Sorry, folks. I’m an immoderate Muslim. Why on earth would I want moderate amounts of love, compassion, joy, peace, or the countless other positive aspects Islam brings to my life?”

Ultimately, whether Buddhism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity, or any other -ism, the worldwide push toward fundamentalism is also heartbreaking in that it forces those of us sustained by some sort of faith to have to say what should be obvious: these acts of violence do not speak for us.

A version of this essay has appeared on the Huffington Post blog.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.