The trial of Ieng Sary, Khieu Samphan, and Nuon Chea, three prominent leaders in the Pol Pot regime, continues. The three, who are charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity, had for many years escaped punishment for the 2 million deaths caused by the Khmer Rouge’s rule.

Last week, trial judge Lavergne questioned Nuon Chea, second-in-command to Pol Pot and known as “Brother Number Two,” about his understandings of Buddhism’s relationship to the party. The answers, coming from a man who was raised Buddhist but who was also an integral figure in a regime that named Buddhist monks as an enemy, are shocking. Unsurprisingly, during the trial, Nuon Chea denied that the Khmer Rouge had tried to eradicate Buddhism within Cambodia, saying that those who thought that defrocking monks and destroying pagodas was an attempt to destroy Buddhism “don’t understand the real meaning of religion,” because Buddhism “is the morals, the meditation, and your intelligence,” not its places of worship.

Here is most of the conversation about Buddhism between Judge Lavergne and Nuon Chea that took place on December 13 and 14—it’s from the court transcripts, available to read in their entirety here.

Q. Mr. Nuon Chea, when you use the word “compassion,” should one understand that it also has a religious connotation for you? Does it refer, in some way, to the Buddhist religion?

A. That is correct. It is also related to the Buddhist religion, which states that do not use the authority; we need to feel compassion for the people. And I studied that well. I had the compassion for the people as an individual, not from the point of view of a revolutionist because I did not get to join the revolution at the time.

Q. Mr. Nuon Chea, you also said: “Cambodians are Buddhist even if they have joined the Communist Party, they kept a respect for Buddhism and its principles.” Can you tell me what principles you were referring to? Would those include the principle of rejecting all kinds of violence, or a principle consisting in respect for human life?

A. My personal view is that the revolution is based on the notions of materialism, as in Buddhism the idea of materialism is also used. So in the revolution, the notion of dialectical materialism is similar to that in the Buddhist religion—that is, people are educated to feel compassion for one another, to help one another.

However, in revolution, in times of necessity when we are invaded, then we shall resist. If we are confronted with arms, then we shall respond accordingly. Even in religion, I also noticed this approach. For example, in the conflict of the war on the land and the water, they also used arms, though I could not recollect well.

So in certain instances, they are the same, but in other occasions, the Buddhist religion is more on the notion of patience. But for the revolution, we restrain from exercising the power of the authority or to be womanizers or heavy drinkers or relying much on money. In Buddhism, the notion is quite similar—that is, try to restrain from exercising power, womanizing, or heavy drinking or gambling. So, the two approaches could coexist, based on my personal view.

Q. So according to you, Mr. Nuon Chea, a revolutionary in the Communist Party of Kampuchea can take on board the principles of Buddhism, and can that person have the same feelings of compassion vis-à-vis all mistreated victims, all of those who were victims of arbitrary arrest or detention? Treatment that leads to the state of slavery and victims that undergo forms of violence that are unjust?

A. It is not identical in every aspect. It is my view that the revolution means to use the labour—that is, physical labour as well as the mental labour—to build the country to make it progressive. Religion, on the other hand, relies on compassion and sympathy, as I stated earlier. If there is no use of labour in the revolution, in order to build the country and the forces, it would not get the result.

And also, similarly, in the Buddhism, there is also a practice, to a certain extent—for example, meditation is also a form of self-rebuilding, so that our mind is cleaned and pure. On the revolution, we had to get rid of self-ego. In simple terms, it means self-ego—so there is always a self-ego, and in every self-ego—then it means there would be individualism, and if there is individualism it means there would be privatism, and if there is privatism, there would rise the conflicts. Therefore, in Buddhism, they tried to get rid of selfishness. So, a similar approach is used.

However, in other instances, they are not similar. Where they are the same, then they can be used exchangeably, and for those aspects which are not the same, then we put it aside. So the theories, both in the revolution and in Buddhism, are sometimes the same and sometimes different. For the daily living, in Buddhism, we relied on our intelligence, on our meditation; and on the revolution, we tried to work hard and we tried to focus on our work—that is also a form of meditation—and when we used our intelligence to resolve the problems, we are in a similar approach. This is my personal understanding.

What do you think of his answers? I found them both rife with hypocrisy and also unnerving. And once you think about how these theories were put into practice, with millions of people executed or overworked to death, his answers become horrendous. You can learn more about the Pol Pot regime here.

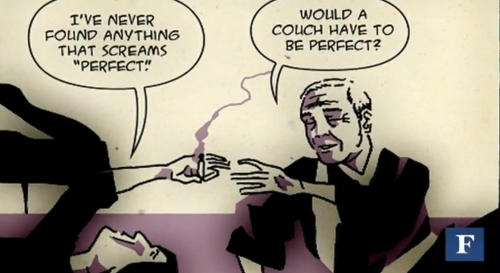

The day after that conversation, Forbes’ and Jess3’s graphic novella The Zen of Steve Jobs was released. In the promotional video on Forbes’ website, we get to see some sneak peeks of the novella’s fictionalized account of the relationship between Jobs and Kobun Chino Otogawa: Jobs and Otogawa practicing walking meditation, Jobs and Otogawa having an argument, Jobs and Otogawa…passing a joint?

Well, that could be a cigarette, or a cigar, or some misplaced incense…

Actually, no, that definitely looks like a joint. But maybe we’ll give Forbes and Jess3 the benefit of the doubt and call it a hand-rolled cigarette for now. (The two are talking about buying furniture, by the way.) If anyone has already bought and read the book, let us know what you think…and what this scene is all about.

To end on a merrier note more suitable for the holiday season, here is a photo from the Washington Post of the head of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, Ja Seung, and Catholic priest Lee Jeong-Joo celebrating a Christmas tree lighting ceremony at Jogyesa Temple in Seoul. The temple, the Post says, “installed Christmas trees to promote peace and understanding between religions.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.