The sacred garden marking the Buddha’s birthplace in Lumbini, Nepal, has become a pilgrimage site for Buddhists around the world. But one of its native inhabitants may be getting squeezed out as developers lobby to build hotels on the 256-acre Lumbini Crane Preserve, where Sarus cranes have lived since the Buddha’s time.

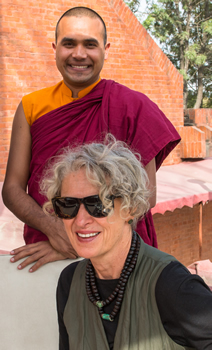

The ongoing effort to protect the vulnerable Sarus cranes, the tallest flying bird in the world, is the subject of the new documentary Sanctuary by artist and environmental activist Lillian Ball. The 30-minute film, which premieres on November 16 at the Tibet House in Manhattan, follows Nepalese Theravada monk Venerable Metteyya as he champions the cause of cleaning up the sacred garden and preventing further development from driving out wildlife. In the film, Venerable Metteyya, sharing the story of when a young Siddhartha saved a wounded crane, makes the case that environmental conservation and Buddhism go hand-in-hand.

They are trying to turn it into Buddhist Disneyland. –Lillian Ball

Before making the film, Ball—a Buddhist practitioner from New York—worked for years on a land preservation committee on Long Island’s North Fork. She also created the WATERWASH project, which helps communities restore overdeveloped wetland areas, turning them into educational parks that also remediate stormwater runoff, which is a leading cause of pollution. Ball’s ecological artwork has received various awards, including two New York State Foundation for the Arts grants, a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in Visual Arts, and a National Endowment for the Arts grant.

Tricycle spoke with Ball about her new documentary, what has changed since she filmed it, and her plan to turn the Lumbini Crane Sanctuary into an example of what Buddhist environmentalism can be.

What are the forces driving the Lumbini Crane Sanctuary project?

The Lumbini Development Trust (LDT) is a government organization that is supposed to be taking care of the three-square-mile sacred garden, but they are trying to turn it into Buddhist Disneyland. They want to build a giant meditation center, and before that it was four or five hotels. Every time you turn around, there’s a new project to take over the crane sanctuary.

The sacred garden is a UNESCO site, but the LDT does all sorts of things without talking to UNESCO. On one of my first trips to Lumbini, I met a UNESCO worker who was checking in on the area. The LDT had just put up a huge, flashing neon sign that said, “Lumbini! Birthplace of Shakyamuni Buddha!” And he just about had a heart attack. He said, “They didn’t ask us to do that. That’s not right.”

The trust does what they want, and sometimes they ask permission later. Unfortunately, their idea of how Lumbini should be is as tourist trap. And many people are looking to make money whatever way they can—both in and outside the government.

Why doesn’t the sanctuary have legal protections?

The International Crane Foundation (ICF) took out a 50-year lease on the 256 acres of the sanctuary from the LDT in the nineties. It otherwise has no protected status. But the ICF had to stop funding the sanctuary during the Nepalese Civil War (1996–2006). At that time, it was easier to put their efforts toward protecting cranes in India. Since then the trust has not really been honoring the terms of the lease because the ICF wasn’t there to enforce it.

What led to you make this documentary?

I hadn’t set out to make a film. I first went to Lumbini with the Anatta Foundation, which is a global health and educational outreach nonprofit. I joined the Anatta group that was going after the devastating 2015 earthquake. They told me about the effort to preserve the crane sanctuary and put me in touch with a young monk named Venerable Metteyya, who is featured prominently in the film. He has been working to protect the cranes for a long time, and he showed me all the problems they were facing and what they were doing about it.

When I came back to New York, I hosted a successful fundraiser for the crane sanctuary with Buddhists and artists, but I wanted to do more. Then Venerable Metteyya told me, “You have to come back.”

Related: Building the Buddha’s Birthplace

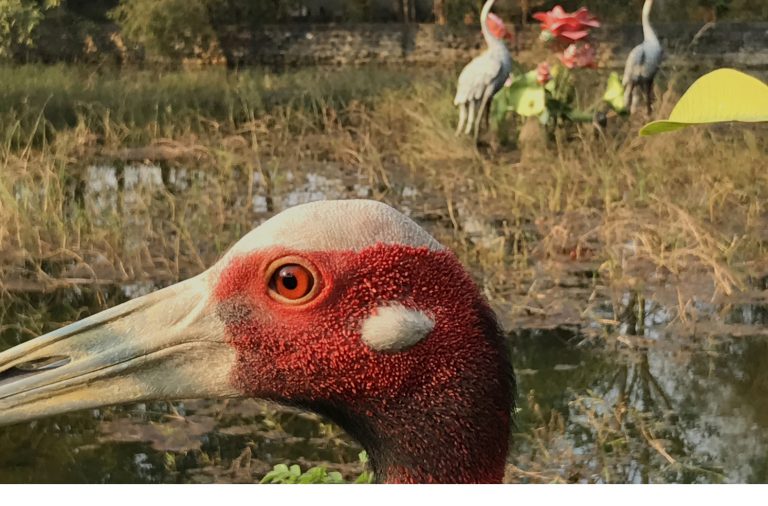

The second time I went to Lumbini, I started shooting. Venerable Metteyya took me to his favorite walks, and I had my iPhone, so I would tape things. I spent a lot of time in the crane sanctuary shooting footage of the cranes and fell in love with them. They’re so gorgeous. They’re the world’s tallest flying bird—six feet tall when they’re healthy— and they have amazing red heads. They’re beautiful birds.

After some time, I realized we really had a film. It was not a big budget production, but with the iPhone and my small point-and-shoot camera, we had enough enough footage to make this short version.

One major change since you made the film is that Venerable Metteyya is now the head of the Lumbini Development Trust. How did Venerable Metteyya get the job?

He was appointed by the prime minister. But it was a very long, drawn-out process, because there were three people being considered, and the other two people were huge, rich people who would make donations to the party. And Venerable Metteyya and his supporters had no money.

I never dreamed he would get this job. They’ve already ousted him once, and then he was reinstated.

Why did he get ousted?

Because the politics in Nepal are very intense. I don’t even follow it completely. He got the job in November 2017, after I’d already filmed everything, and then in June, he was kicked out again. And he had to go through the whole appointment process all over again.

His vision for Lumbini is not just for the sacred garden and not just for the crane sanctuary; it’s for the people of Lumbini. And he’s made some progress.

What sort of progress?

He has been working with local people to try and come up with some crafts that they could sell at the pilgrimage site. Currently everything sold at the tourist stall is made in China, and it’s all junk. So Venerable Metteyya and I want to get people painting and making ceramics instead. I designed baskets in the shape of a buddha along with a woman who has been doing basketry with native people in Nepal for 30 years. The baskets are woven from invasive species harvested in the crane sanctuary. The concept is that local people will learn how to weave them and then can sell those instead of the items made in China.

In the film, you show the mango grove where the Buddha was born is completely covered in garbage because no one from the LDT was cleaning up. Has there been any progress there?

Since Venerable Metteyya is now in charge of the LDT, the 200 people who were on salary but never did any cleaning are now picking up trash every week. And Venerable Metteyya bought around 400 garbage cans, so there is somewhere for the trash to go. He also bought solar panels, so the garden’s lights are solar powered now.

The film also shows that some cranes were being kept as pets.

The cranes were basically kept as prisoners at one monastery, which I don’t name because Venerable Metteyya still has to work with them. Even worse, the abbot of the monastery has written a book about how the cranes came to join him, when, in fact, they were captured from the rice fields and their wings were clipped. They keep them fenced up and feed them really crummy dough balls.

We want to rescue those cranes, but they’re damaged, so they can’t live in the wild. We want to move those cranes to a conservation museum or education hall so that children can learn more about them. Some kids will shake crane eggs or injure cranes by playing with them. So we want to educate them as well.

Do you intend to make a follow up to the documentary?

I’d like to make a second part to show what’s going to happen with Venerable Metteyya now—both in this position and in the other things he’s still doing.

He is 32 years old, but his CV is really impressive. He also runs the Metta School, which serves hundreds of children in Lumbini, and started the Karuna Girls College and the Peace Grove Nunnery. When he was a teenager, he saw that all the girls from his public school had disappeared because they were married off, so he set up the nunnery as a place where girls who don’t want get married at 12 could go. Most of them don’t stay nuns, but they at least have a chance to get an education and escape a very dismal existence.

Related: Video Teaching: Venerable Metteyya on Addiction

He’s also building a hospital now, which will be the only hospital in the area. He is an amazing, dynamic guy, but he’s got a little much on his plate.

So the second part of the film is, I think, very important. But the first part of the film is where the international Buddhist community has to realize that this is all being done by the government of Nepal, supposedly in the name of the Buddha. But in fact, really more for kickbacks.

How does your Buddhist practice relate to environmentalism?

Buddhism’s connection to environmentalism is part of why I became a Buddhist. Buddha was born under a tree, enlightened under a tree, and died under a tree.

But rather than being angry about environmental injustice, it’s better to use skillful means to get things done. Bhikkhu Bodhi says there’s such a thing as righteous indignation, which is perfectly acceptable anger. But daily anger and frustration is not helpful; you can’t build on it.

In Long Island, I’ve served on a land preservation committee for the last 12 or 15 years, and often I’ve worked alongside Trump supporters. So I’ve had to learn how to talk to people and listen to them. Skillful means can really help. And it’s much more productive than anger.

What’s the end goal of your work in Lumbini?

I’m hoping that once the crane sanctuary is preserved, I’ll be able to help design a nature walk with signage that teaches people about the various plants and birds and explains the story of how Buddha rescued a crane. It would be similar to what I’ve done with the different WATERWASH projects.

We have a chance to take millions of Buddhist tourists and make them care about conservation, because not only have the tourists forgotten, but the monks have forgotten, or they wouldn’t be doing what they’re doing. They wouldn’t be building giant gold Buddhas instead of helping preserve the nature that’s there. We have to reintroduce people to the original teachings of Buddha.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.