Mahayana

Mahayana Buddhism invites practitioners to follow the bodhisattva ideal, striving for enlightenment to benefit all beings. Its scriptures explore themes such as emptiness, compassion, and the skillful means to guide others along the Buddhist path. Over the centuries, Mahayana took root across Asia and became the dominant form of Buddhism in East Asia, giving rise to a variety of schools and practices, such as Pure Land and Zen. Today, it is practiced worldwide, offering an expansive vision of the Buddhist path that embraces diversity while upholding its core values.

Table of contents

- Origins and Development

- Mahayana Scriptures and Teachings

- Buddhas and Bodhisattvas

- The Bodies of a Buddha

- Pure Lands

- Emptiness in the Mahayana

- Yogacara and Mind-Only Thought

- Buddha-Nature and the Potential for Awakening

- The Mahayana Bodhisattva Path

- Skillful Means and Compassionate Action

- Merit and Devotional Practices

- Mahayana Across Cultures

Origins and Development

Mahayana Buddhism, or the “Great Vehicle,” emerged in India around the turn of the first millennium, with some scholars pointing to an even earlier emergence. Its beginnings are difficult to pinpoint, in part because early adherents did not set themselves apart as a separate group or school. Scholars have proposed various origins, with some seeing it rooted in lay communities, while others view it as originating in forest-dwelling renunciants. Evidence now suggests that the Mahayana approach was first promoted by monastics who lived within already established communities but followed new scriptures and understandings of Buddhist philosophy and practice.

The appearance of new Buddhist sutras was a defining feature of the Mahayana movement. Presented as the advanced teachings of the buddhas and bodhisattvas, these Sanskrit scriptures reimagined doctrines such as emptiness (Skt.: sunyata) and compassion (karuna), elevating the bodhisattva ideal above the arahat’s goal of personal liberation. Instead of seeking complete enlightenment and nirvana, a bodhisattva vows to stay in the world to assist all beings.

Mahayana tradition also redefined the nature of a buddha. Shakyamuni was no longer only a historical figure who attained enlightenment and entered nirvana but also a transcendent, cosmic presence whose teachings—along with those of countless buddhas and bodhisattvas—resound in pure lands and celestial realms.

New devotional and visionary practices centered on these buddhas and bodhisattvas. The emphasis on universal salvation, along with forms of chanting, visualization, and merit-making, helped the movement spread among householders. Traveling merchants—many devoted to Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion—carried these practices along trade routes.

Mahayana cannot be traced to a single location, author, or sect, yet its philosophies and practices flourished across Asia. Teachings on emptiness, buddha-nature, and Yogacara philosophy profoundly shaped Buddhist history, as did the development of Pure Land, Zen, and Vajrayana traditions—all within the Mahayana fold.

Though its earliest history remains partly obscure, Mahayana’s scriptures offer a compelling entry point for understanding what set this influential movement apart: an expansive vision of the Buddhist path, rooted in compassion, philosophical innovation, and the aspiration to liberate all beings.

Mahayana Scriptures and Teachings

New scriptures emerging in India around the turn of the first millennium provide evidence of a self-conscious movement, as many even use the term “Mahayana” in their titles. These works reinterpret Buddhist thought, consistently emphasizing the bodhisattva path, the doctrine of emptiness, and the innate buddha-nature present in all beings. The aspiration to awaken for the sake of others, called bodhicitta, is also a central theme.

Despite a shared focus on certain teachings, Mahayana sutras are highly diverse. Many are attributed to the Buddha himself, though historians and non-Mahayanist schools question this claim. Some sutras explain that their teachings were given by the Buddha in other realms or secretly entrusted to bodhisattvas to be revealed only at the proper time. In certain Mahayana scriptures, the Buddha authorizes advanced bodhisattvas to teach in his stead. In the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra (Skt.: Prajnaparamitasutra), for example, bodhisattvas expound the doctrine of emptiness, while in the Vimalakirti Sutra, a lay merchant delivers profound Mahayana teachings.

New Mahayana scriptures became influential far beyond India, as they were translated into and written in Central Asian, Chinese, Tibetan, and other languages. The Mahaparinirvana Sutra, Lotus Sutra, and Avatamsaka Sutra introduced the vast cosmologies that characterize Mahayana thought and shaped the formation of major traditions in East Asia.

Claiming superiority over earlier approaches, Mahayana texts sometimes denigrate earlier approaches to the Buddhist path by calling them the “lower” or “puny” vehicle (Skt.: hinayana). Even revered arhats such as Shariputra are sometimes portrayed as hesitant or puzzled when faced with Mahayana doctrine. Teachings like emptiness are presented as too advanced for some audiences, underscoring their profundity.

The Mahayana sutras’ unique blend of visionary imagery, philosophical innovation, and devotional rituals helped inspire a significant Buddhist movement. Proponents of this approach argued for its universality—everyone should follow the bodhisattva path.

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas

In early Buddhist thought, there could be only one buddha at a time. Shakyamuni, the buddha of our age, was part of a long series of awakened beings who have appeared in the past and will continue to arise in the future. Shakyamuni became a bodhisattva (Skt.; Pali: bodhisatta)—a being intent on achieving enlightenment—when he met the buddha Dipamkara (Pali: Dipankara) in a previous life and vowed to become a buddha himself. In early Indian Buddhism, and in Theravada today, the term bodhisattva refers only to a buddha-to-be during the quest for enlightenment.

In Mahayana traditions, which include Chan, Zen, and Tibetan Buddhism, there are many bodhisattvas. Indeed, anyone who strives to become awakened for the sake of all beings can take the bodhisattva vow. In these traditions, everyone is encouraged to follow this path. The vow is held by ordinary practitioners and the celestial bodhisattvas who are central objects of devotion.

Among the Mahayana bodhisattvas, Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, is especially prominent. Known as Chenrezig in Tibetan and Guanyin in Chinese, this figure appears in both male and female forms and inspires deep devotion across the Mahayana world. His followers regard the Dalai Lama as Avalokiteshvara’s human embodiment.

Mahayana cosmology also allows for more than one buddha at a time. In the Lotus Sutra, Shakyamuni meets the buddha Prabhutaratna in a jeweled tower, and together they affirm the sutra’s value. Amitabha, the principal buddha in the Pure Land traditions, resides in his own paradise, receiving those who call upon him. The proliferation of buddhas and bodhisattvas expanded Buddhist cosmology and inspired new devotional practices.

Female bodhisattvas and goddesses became increasingly prominent in Mahayana art and literature. Prajnaparamita, a deity who embodies the perfection of wisdom, is honored as the Mother of all Buddhas. Tara, a key figure in Tibetan Buddhism, is variously described as a buddha, a goddess, and a bodhisattva. The distinction between these terms is not always clear.

As buddhas and bodhisattvas flourished in the Mahayana, new ways of characterizing their timeless realization, limitless powers, and countless manifestations also emerged. These cosmic portrayals set the stage for Mahayana’s vast vision of pure lands and celestial realms.

The Bodies of a Buddha

Mahayana scriptures introduced new interpretations of what it means to be a buddha. Buddha Shakyamuni had long been portrayed in superhuman terms, marked by the thirty-two characteristics of a great man (Skt.: mahapurusa), and his relics were believed to retain his presence after death. Describing the mind of a buddha had always been challenging, however, as it was said to be beyond conceptual understanding. New Mahayana doctrines built on earlier foundations to account for the vast qualities of buddhas and their limitless ways of manifesting in the world.

Indian Mahayana scholars commonly taught that a buddha has three bodies (Skt.: trikaya): the emanation body (nirmanakaya), the enjoyment body (sambhogakaya), and the truth body (dharmakaya). The emanation body is how buddhas manifest in the world, appearing in many beneficial forms. The enjoyment body is a radiant, exalted form accessible in visionary realms. The truth body refers to the boundless qualities of a buddha’s mind, and it is linked to ultimate reality. This three-part model helped explain how a buddha could simultaneously appear in many forms, teach beings in distant realms, and remain present long after their historical lifetime. It bridged the human story of Shakyamuni with the Mahayana vision of a cosmic, timeless Buddha.

The three bodies model translates into different forms of Mahayana Buddhist practice: The manifestations of a buddha can be directly seen, accessed through visualization practices, or realized inwardly at the deepest levels of the mind. Recognizing the truth body is described as awakening to emptiness, nondual awareness, or ultimate reality.

In Indian Buddhism, debate and speculation culminated in increasingly nuanced models, some of which described four or five bodies of a buddha. The Tibetan Buddhist tulku system drew heavily from these theories. Prominent lamas are often regarded as emanations of enlightened masters or bodhisattvas, and the Tibetan word “tulku” (sprul sku) directly translates the Sanskrit term for emanation body.

As buddhas were described in new ways, their powers expanded. They were said not only to emanate countless bodies but also entire worlds. Pure lands became central to Mahayana devotional life as the tradition spread beyond India.

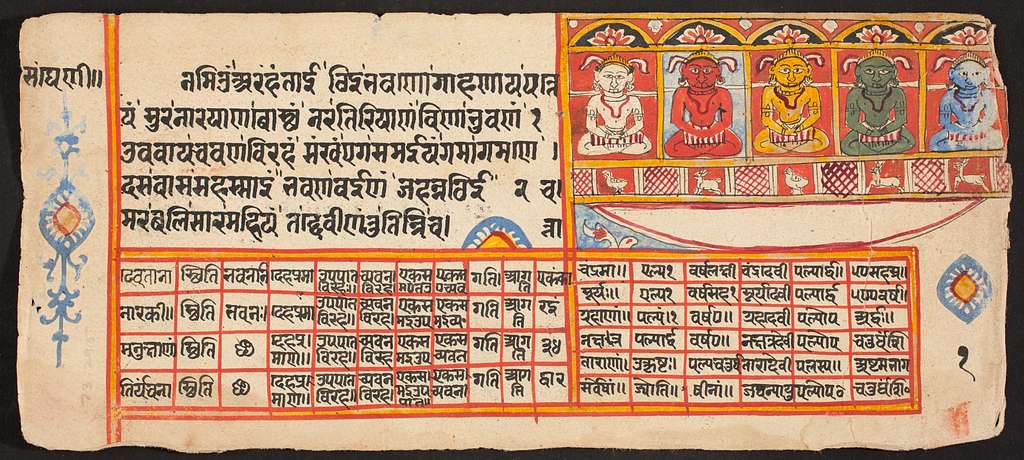

Pure Lands

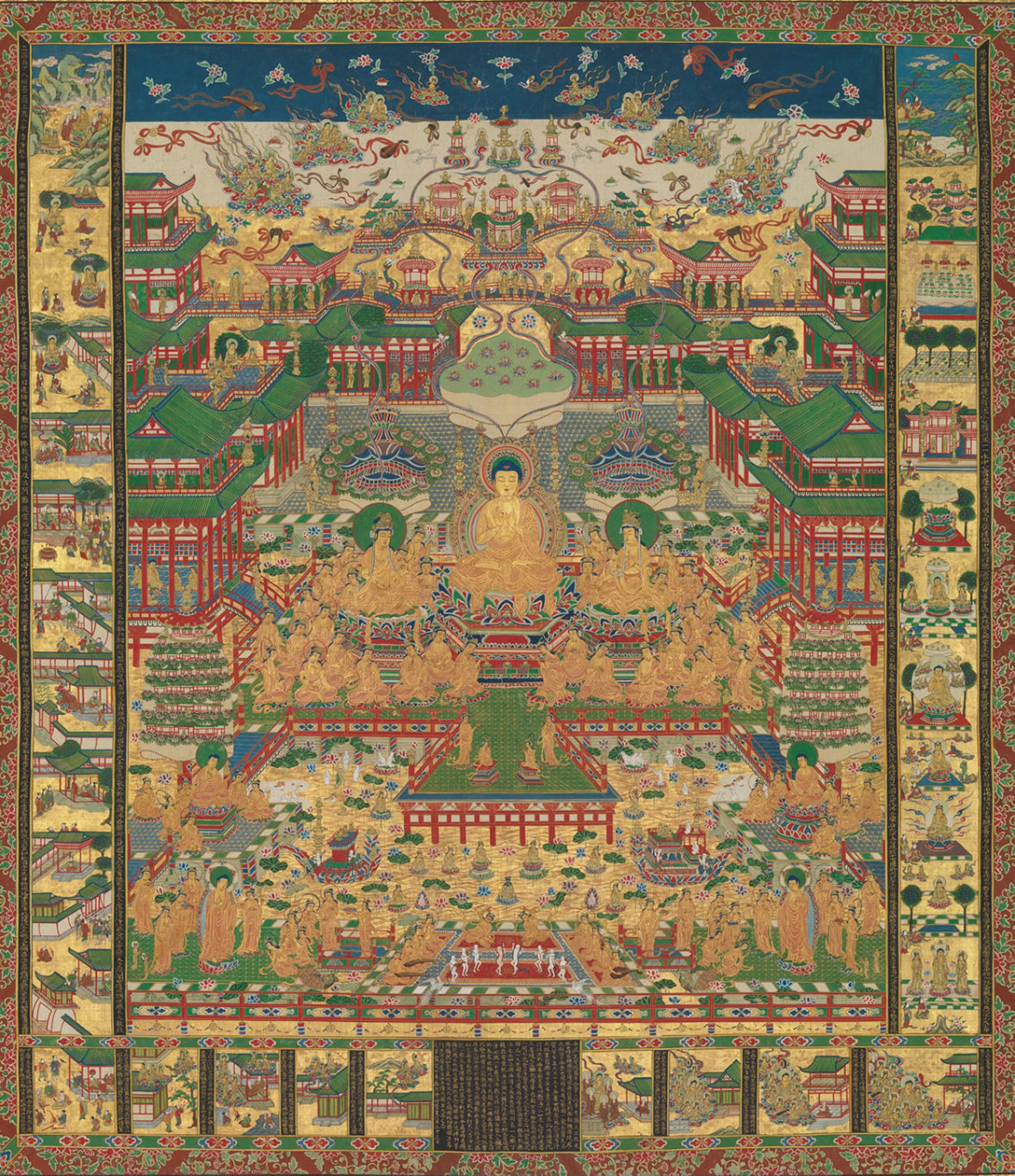

Mahayana scriptures introduced new worlds on a cosmic scale, like a Buddhist multiverse stretching across time and space. Pure lands, or buddha-fields (Skt.: buddhaksetra), were envisioned as destinations after death—not heavenly realms of pleasure but places where conditions are ideally suited for liberation. These realms arose from the compassionate vows of a buddha.

Pure lands offered hope during what many traditions saw as a degenerate age, when moral decline and a scarcity of awakened teachers made progress difficult. In such times, rebirth in a pure land, in the presence of a living buddha employing skillful means to teach, was viewed as the surest way to continue on the path toward enlightenment.

Created through a buddha’s merit and intention, a pure land is described as a place where the path is vastly easier, sometimes even effortless. Simply being in a buddha’s presence could bring liberation. Certain scriptures also taught that pure lands could be accessed while alive through visualization practices, such as the “recollection of the Buddha,” in which one vividly calls to mind a buddha’s qualities.

Mahayana texts detail many pure lands. The most famous is Amitabha’s Sukhavati, the “Land of Bliss” in the West, though others exist in every cardinal direction. This vision expanded Buddhist cosmology beyond the traditional six realms of rebirth and opened new possibilities for favorable rebirths. Pure Land devotion became deeply embedded in many Mahayana traditions.

While transcendent in origin, Pure Land thought also inspired efforts to create pure lands in society through ethical conduct, compassion, and good governance. In China, such ideals sometimes informed social reform movements and even revolution.

Mahayana philosophers further emphasized that a pure land can be experienced here and now. Through faith and cultivating pure perception, one’s view of the world can be transformed, revealing this very place as a pure land. Whether seen as an auspicious realm for rebirth or as an altered perception of reality, Pure Land teachings reflect the Mahayana emphasis on emptiness. Because all phenomena lack a fixed essence, they can be understood in multiple ways.

Emptiness in the Mahayana

Emptiness (Skt.: sunyata; Pali: sunnata) lies at the heart of Mahayana philosophy. This emphasis reframed core Buddhist concepts and dramatically shifted the nature of practice.

Mahayana scriptures commonly teach emptiness by analyzing the relationship between objects and their parts, a method found in texts that predate the Mahayana. On its own, no single part of a car (or a chariot)—a wheel, a seat, or an axle—can be called a “car.” It is only when these parts are assembled that the concept car makes sense; the term itself is just a label for the collection of parts. Each part can also be analyzed in the same way, so in the end, nothing can be said to exist without being in relationship to other things.

Far from describing a grim void or a nihilistic outlook, emptiness explains why objects and persons do not have an independent, fixed existence. As a contemplation, it is especially powerful when used to investigate the nature of personal identity. Emptiness can help to loosen the grip of attachment and aversion. For Mahayana practitioners, this deepens compassion: If all beings and experiences arise in relationship, then our lives are inseparably connected with the lives of others. Their well-being is bound up with our own.

Emptiness is also taught through the rubric of the two truths: the conventional and the ultimate. At the conventional level, things such as cars exist and function in the world. But, ultimately, the concepts used to describe such objects are empty. Words and concepts express conventional truth; the ultimate truth is the emptiness of the idea itself. The Heart Sutra captures this in the well-known maxim: “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.”

The philosopher Nagarjuna (c. 2nd to 3rd centuries CE) taught that all Buddhist concepts should be seen through the lens of the two truths. In Root Verses on the Middle Way, he shows why the conventional always depends on the ultimate, and vice versa. Even samsara and nirvana are interrelated concepts, empty of a fixed essence. Nagarjuna’s works were foundational for the Madhyamaka (“middle way”) philosophy, which became a dominant interpretation of emptiness.

While Madhyamaka offered a powerful account of emptiness, some later Mahayana philosophers sought further explanations, particularly about the workings of the mind and the persistence of karma across time. These questions set the stage for the development of Yogacara thought.

Yogacara and Mind-Only Thought

Madhyamaka philosophers underscored the emptiness of all phenomena, but their arguments raised new questions: How does karma persist over time? If everything is “empty,” how do perception and memory function? Later, Mahayana thinkers in the Yogacara school developed detailed explanations of the mind to address these issues.

Originating in India, Yogacara was systematized in the 4th to 5th centuries by the scholar-monks Asanga and Vasubandhu, who are remembered as half-brothers. Its central idea, often translated as mind-only or consciousness-only (Skt.: vijnaptimatra), emphasizes that the mind shapes all perception. This doesn’t mean the external world does not exist—a common misunderstanding, claimed by some—but that our experience of it is always filtered through habits, expectations, and past conditioning. How to understand and interpret Yogacara teachings is still debated.

Yogacara philosophers analyze mental processes to understand suffering. This has been illustrated through the example of someone mistaking a piece of rope for a snake and reacting with shock and fear. Seeing a “snake” is an imagined mental projection that depends on the rope, which is called the dependent nature. Recognizing that it is only a rope is the perfected nature. These “three natures” (trisvabhava)—the imagined, dependent, and perfected—show how misperception creates suffering, and how seeing things as they truly are, free from false projections, leads to freedom from fear and suffering.

As it developed, the Yogacara school established models for understanding how habitual patterns (vasanas) and mental afflictions (klesas) shape experience. Memories and emotional impressions remain active at a deep level of the mind known as the storehouse consciousness (alayavijnana), sometimes referred to as the “Buddhist unconscious.” In the 6th and 7th centuries, Dignaga and Dharmakirti introduced new theories of knowledge (pramana) and cognition—including the concept of reflexive awareness (svasamvedana)—which were incorporated into Yogacara thought.

Yogacara philosophy spread widely in India, East Asia, and Tibet, shaping Buddhist practice in diverse ways. In Zen, the insight of mind-only converged with the experience of awakening to the nondual nature of reality. In Tibet, Yogacara thought fueled debates about the nature of mind and its relationship to emptiness, deepening philosophical inquiry into perception and consciousness. It also informed explanations of deity yoga and visualization practices.

Alongside the doctrine of buddha-nature, Yogacara provided a framework for understanding the obstacles to awakening and the mind’s capacity to realize it, leaving a lasting mark on Mahayana philosophy and practice.

Buddha-Nature and the Potential for Awakening

In Mahayana Buddhism, buddha-nature (Skt.: tathagatagarbha) is the innate potential for enlightenment present in every being, regardless of their current problems or confusion. It affirms that awakening is not something to be created or acquired from outside but a natural quality to be uncovered.

The teaching arose in contrast to more austere Buddhist views that treated nirvana as a remote goal, attainable only after lifetimes of effort. Some schools even taught that awakening was possible only for those of a particular disposition. By contrast, the buddha-nature doctrine holds that the mind’s intrinsic luminosity remains untouched by defilements—however obscured it may be—and that liberation is universally accessible, not reserved for a spiritual elite.

The Mahaparinirvana Sutra, likely further compiled outside of India in the 2nd or 3rd century CE, is among the earliest Buddhist texts to emphasize buddha-nature. It also includes similar terms, such as “buddha element” (buddhadhatu), that convey the same idea: All beings have the potential to become buddhas, and the mind’s purity is always present whether or not we recognize it.

As the doctrine of buddha-nature became more widespread, it led to varying interpretations. Yogacara thinkers framed it as a profound cognitive transformation, while others treated it as an eternal reality. Critics argued that the latter view risks contradicting the teachings of emptiness, which denies any fixed essence. In Tibet, the controversial philosopher Dölpopa (1292–1361) united buddha nature and emptiness in his presentation of other-emptiness (Tib.: zhentong).

Across Mahayana Buddhist traditions, buddha-nature informed devotional practice and meditation, reframing the goal of the path. Liberation, in this view, is not about becoming something new but about realizing what has always been true. This shift has had lasting implications for ethics, compassion, and spiritual training. By suggesting that ordinary people are, in some essential way, already the same as a buddha, buddha-nature provides a doctrinal basis for the Mahayana emphasis on the universality of the bodhisattva path.

The Mahayana Bodhisattva Path

Mahayana scriptures present the bodhisattva path as open to everyone. Early in the movement, it was taken up primarily by monastics who could devote their lives to practice, but as Mahayana spread, lay practitioners also embraced it.

At the heart of the bodhisattva path is the aspiration to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings, even those who oppose or harm us. This intention is expressed through the bodhisattva vow and the cultivation of bodhicitta, the “aspiration for awakening,” which combines compassion with the resolve to realize buddhahood for the sake of others.

Various texts define bodhicitta differently, but it’s often described as having two forms. Conventional bodhicitta is the compassionate wish to attain enlightenment, to help all beings, and to deliver beings to the same understanding. Ultimate bodhicitta is the direct realization that all phenomena are empty of intrinsic existence. Mahayana practices often integrate these perspectives, uniting compassionate action with insight into emptiness.

A core feature of the Mahayana path is the cultivation of the six perfections (Skt.: paramita): giving, morality, patience, effort, concentration or meditative absorption, and wisdom. These are developed gradually, with even small acts serving both to benefit others and to train the mind. For example, in offering a material gift, one contemplates that the giver, gift, and recipient all arise dependently and have no fixed essence.

Bodhicitta and the perfections are central across Mahayana traditions. In India, Shantideva’s 8th-century The Way of the Bodhisattva (Skt.: Bodhicaryavatara) became a classic text, especially influential in Tibet. In East Asia, the Avatamsaka Sutra (“Flower Garland Sutra”) and Diamond Sutra also laid out the foundations of the path.

In a sense, Mahayana thought reoriented the Buddhist path: As a bodhisattva, one practices not to become a buddha but because one is already a buddha who has yet to realize it. Practice is thus a process of recognizing and embodying what is inherently present, aided by the skillful means and varied teachings that guide beings toward this awakening.

Skillful Means and Compassionate Action

Skillful means (Skt.: upaya) refers to a teacher’s ability to tailor actions and instructions to a specific person or audience. In Mahayana thought, it is closely linked to compassionate action: The bodhisattva seeks to relieve suffering using whatever methods are most effective.

Shakyamuni Buddha employed skillful means by using local languages, familiar imagery, and metaphors that made his teachings accessible. His dialogues at times resembled those of Socrates, allowing students’ questions and assumptions to guide the discussion. He likened his teaching to a raft: useful for crossing a river but to be set aside once liberation is reached. Practices and words have value only insofar as they help beings awaken.

In Mahayana texts, composed hundreds of years after Buddhism’s beginnings, skillful means took on a broader meaning: There is ultimately one Buddhist path—the Mahayana—and the variety of teachings is meant to bring people to this realization. The Lotus Sutra tells of a father who rescues his children from a burning house by offering each the kind of cart they most desire. Once outside, they all receive something far better. In the same way, Buddhist teachers guide students according to their needs but ultimately reveal the whole Mahayana teaching.

Skillful means also accounts for unconventional or seemingly contradictory teachings. A Tibetan lama or Zen master may flout tradition or give counterintuitive advice because it benefits a particular student. Yet this adaptability can be misused; some teachers have exploited students under the guise of skillful means. Discerning genuine compassion from abuse remains an ongoing concern in Buddhist communities.

The connection between skillful means and compassionate action is emphasized in Mahayana teachings and ways of life. Practitioners strive to employ the most effective methods to alleviate the suffering of those in need. This compassionate view informed healing practices and major humanitarian efforts. The Mahayana explanation of skillful means also reshaped older ideas, such as the transfer of merit, imaginatively extending it to all beings.

Merit and Devotional Practices

In early Buddhism, merit (Skt.: punya) was understood to increase in proportion to the recipient’s worthiness. Donations and offerings to the Buddha or the monastic community were therefore highly valued. Transfer of merit shaped the relationship between lay and monastic communities, as lay supporters dedicated the merit from their gifts to the welfare of ancestors or to achieving worldly or spiritual aims.

In Mahayana traditions, the transference of merit was reframed. Devotional practices often follow a three-part structure: first, generating bodhicitta, the motivation to practice for the benefit of others; next, supplicating or venerating an object of devotion such as a buddha, bodhisattva, or spiritual teacher; and, finally, dedicating the merit from the practice to all beings. Sharing the results of positive actions universally is a cornerstone of Mahayana devotional life.

Merit flows in both directions. Advanced bodhisattvas and buddhas, who have accumulated vast stores of merit, can share that merit with beings in need. In Pure Land traditions, those who call upon Amitabha share in his merit and are reborn in his pure land. Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, likewise aids distressed beings through his accumulated merit. In East Asian rituals, merit is often dedicated to a specific bodhisattva at the close of the ceremony.

In Tibet, devotional practices often focus on the guru (lama), who may be visualized in the form of a buddha. Foundational practices such as prostrations, confessions, offerings, and guru yoga are performed to honor the lama as a source of merit and blessings. Merit may also be dedicated to the lama’s health and long life. While this model has roots in Indian tantric traditions, it became a central part of daily practice in Tibet.

Skillful means provided a framework for new forms of merit transfer, adapting the practice to different cultures and times. As Mahayana Buddhism spread across Asia, its adaptability allowed devotional life to flourish in diverse forms, leading to its many cultural expressions today.

Mahayana Across Cultures

The growth of Mahayana Buddhism across Asia, and more recently the West, shows how its core doctrines have been adapted to diverse cultural contexts. While united by the bodhisattva ideal and teachings on compassion and emptiness, its practices vary widely from place to place.

In China, Mahayana Buddhism integrated with Daoist and Confucian ethics, practices, and cosmology. The Tiantai and Huayan Buddhist schools gained recognition for their comprehensive philosophical systems. At the same time, Pure Land Buddhism provided an accessible practice of invoking the Amitabha Buddha for rebirth in his blissful realm.

Korean and Japanese Buddhism drew from these Chinese influences, developing their own distinctive meditation schools—Seon in Korea and Zen in Japan—and devotional practices. The Japanese Nichiren school emphasized the Lotus Sutra’s power and individual responsibility for spiritual advancement. Vietnamese Mahayana, shaped by both Indian and Chinese influences, became internationally known for humanistic or Engaged Buddhism through the work of Thich Nhat Hanh and others. In Taiwan, Mahayana principles and ethics remain widespread.

All Tibetan Buddhist schools are rooted in Mahayana philosophy, combining compassion and emptiness with strong devotional ties to the lama as a source of blessings and merit. Tibetan Buddhism also shaped the Himalayan cultures of Nepal and Bhutan and spread into Mongolia.

In Bangladesh’s Chittagong Hill Tracts, small Mahayana communities, such as the Jumma, center their rituals on bodhisattvas and the concept of merit-sharing.

In the West, Mahayana has taken on new forms, while some communities maintain traditional practices. Its principles have also been applied to contemporary causes, including environmental activism and social justice.

Today, immigration, global travel, and the spread of Buddhist thought have helped to establish Mahayana communities around the world. Despite its diversity of expression, Mahayana remains bound together by a shared ethical commitment: cultivating compassion, realizing emptiness, and dedicating the benefits of practice to all beings.

Buddhism for Beginners is a free resource from the Tricycle Foundation, created for those new to Buddhism. Made possible by the generous support of the Tricycle community, this offering presents the vast world of Buddhist thought, practice, and history in an accessible manner—fulfilling our mission to make the Buddha’s teachings widely available. We value your feedback! Share your thoughts with us at feedback@tricycle.org.