I have just returned from twelve days in Poland. I went as a photographer and participant in an interfaith meditation retreat at Auschwitz organized by the Roshi Bernard Glassman and his new Zen Peacemaker Order. During American Thanksgiving week a group of 150 people—Jews, Christians, Buddhists, and Sufi Muslims—gathered for meditation and discussion, to “bear witness” to what happened at Auschwitz fifty years ago, and to listen for the ways in which those events echo in our lives today.

I must start by advising everyone that to tell a Polish joke around me is to risk my violent wrath. This is a country that has suffered tremendously and is poised for rebirth. Our trauma in the US and in Western Europe ended fifty-one years ago, while theirs did not end until about 5 minutes ago. My own ignorance had left me unaware of the significance of the Warsaw uprising in 1944 (as opposed to that of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943). In the summer of 1944, as the Red Army approached from the east, the Polish resistance staged a major rebellion in an attempt to oust the Nazis and gain control of the government before a potential Communist takeover. But the Russians perversely paused on the east side of the Vistula before entering the cit to take over for the next fifty years. They waited for the Germans to finish their slaughter of 800,000 citizens (the population was 1.3 million in 1939); 90% of the buildings of this beautiful medieval city were entirely destroyed and fewer than 5,000 Poles survived. Every Pole living here today has a family member who died in the Warsaw Uprising, and they speak of an entire generation that lost all its poets and idealists. I was impressed that the current generation of Polish children are all taken on school trips to visit Auschwitz; they seem to be well educated about what the Nazis did to the Jews and to their own people. So although there may be much history for the Poles to reexamine themselves, I suggest we find another ethnic group to kick around (if we must), and if you have a vote, I would urge you to use it to admit Poland into NATO. They need time to heal, and given their position on the map, they will surely need protection again one day.

A couple of days in Cracow. A great undestroyed old European town. Invest here. Visit as a tourist. From Cracow it is an hour by taxi or train to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where many of us spent seven full days. Most people who come here stay for only a few hours. But if you stay for some extended time, you may discover parts of yourself you never expected to find in a place like this.

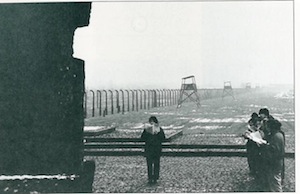

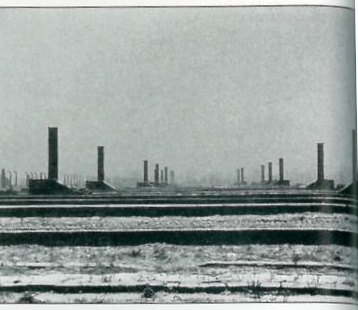

Our group assembled from around the United States, Poland, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Israel, the Netherlands, and Ireland. In attendance were Buddhist teachers and priests, Catholic monks and nuns, Jewish rabbis, and a Sufi imam. We slept on the grounds of the Auschwitz I concentration camp. My assigned roommate was a veteran Zen practitioner from Los Angeles, born in Argentina, whose grandparents, a German Lutheran and German Jew, emigrated in disgust from their country in 1933. We laughed and cried together; he denies he snored. I averaged three hours of sleep and lost all desire for coffee, alcohol, and food. Each day we all walked an hour from Auschwitz I, where we slept, to Auschwitz II, better known as Birkenau (“place of birches”—the Poles pointedly never use the famous German name; they call it “Brzezinka”). Birkenau was a

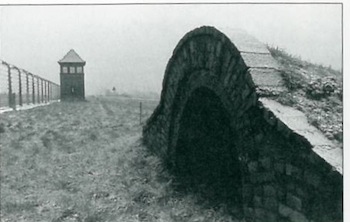

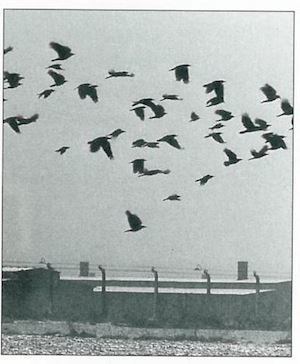

vast complex of ruins left exactly as it was the day the Nazis blew it up. The rail line, which enters the main gate from the south, bisects the camp—women’s barracks and children’s barracks to the west andmen’s to the east. Trains from all over Europe would stop at the center of the camp, where the “cargo” was unloaded and lined up; German doctors, often led by Josef Mengele, would conduct a visual inspection and point prisoners to the work camps on the east and west sides or to the gas chamber at the north end. Homosexuals and gypsies were separated. One of our group, a map from South Carolina named Nolan, objected loudly when an otherwise exemplary tour guide failed to mention the homosexual prisoners in his introductory talk. Nolan also brought great laughter to the grounds of Auschwitz by observing, with a hint of glee, that “in the barracks where the SS men once lived and worked, homosexuals are now gathering to sew pink triangles.” One evening ended (controversially) in a similar tone of joyous defiance, with most of us dancing the hora before a statue depicting a suffering inmate. For me, it was an audacious act of laughing in the Nazis’ faces, as if to say: you tried your best to wipe us off the face of the earth, but you failed miserably.

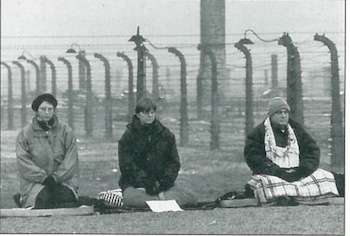

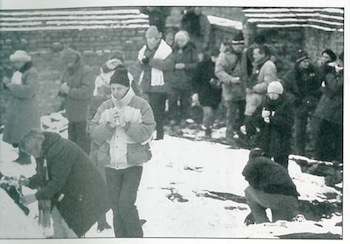

On arrival in the morning, our group split for separate services—Buddhist, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim—then assembled around the tracks where these life-and-death decisions were made. We would form a large ellipse, about 75 yards long, and sit in meditation for 45 minutes. We were each given a list of names from the Nazi “death books” (lists compiled by the Gestapo of the names of prisoners who were put to work but subsequently died; lost are the names of over a million deportees who went directly to the gas chambers). We took turns of 10 minutes each, reading aloud names from the list and adding names from our own experience. I added my own great-grandmother who dies at Bergen-Belsen, a fate I had learned only a month before. It was cold, it was warm, it was sunny, it was gray, and it snowed nearly every day. We sat still, outside in the winter, feeling the changing light, and sounds, and weather all around us. We were mostly comfortable, dressed warmly, but during the war the prisoners here passed colder winters than this dressed only in light striped cotton uniforms and shoes that didn’t fit.

After a sitting period we did kinhin (slow walking meditation) to the gas chamber—crematorium complex 200 yards to the north, where a rabbi led the entire group in reciting theKaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, in Hebrew and in a new English translation as well as German, French, Polish, and Italian. Back outside the main gate for a bowl of soup (no spoon) and a hunk of bread, and then we returned for another meditation period and an interfaith service where there was a signing and the offering of candles. On the last night we descended into the ruin that was the crematorium compound: the undressing area, the gas chamber, the gold extraction area, and the crematorium itself. We offered candles in the snow to the victims who died in that place and whose presence was palpable to everyone. Swiss nuns led us in a lullaby. We walked back from Birkenau to Auschwitz in the dark.

After supper each night the full group met and people spoke of their experiences. A German economist, Stefan Collignon, spoke eloquently of the koan he had received the week before in Korea, “Why do we eat?” Thinking of the potential he saw for the repetition of history, and reminded of the goddess columns supporting the Acropolis in Greece, he concluded that “we eat to hold up the roof”.

A French Zen priest, Michel Dubois, spoke of the pain coming through his heart here and how the more pain he felt, the more joy and love he felt coming through the opening portholes. He felt love arising from the souls trapped in this place, and felt grateful to his relatives and all others who died here.

Sleep was scheduled after the talks, but several of us soon learn that security at the Auschwitz camp was really a trompe-l’oeil (the Polish officials handle this delicate question very well: all barbed wire has places you can pass through if you look hard enough and the guards are seldom seen and never heard). We found the way into the maze and we would walk slowly through the camp for hours in the darkness. The silence was frequently pierced by the wailing of a shofar (traditional Jewish ram’s horn); we would trace the source to find Brian Rich (a Buddhist priest, and now a Sufi Muslim) and Don Singer (rabbi and Zen teacher) at the Execution Wall blowing the horn as loudly and as exuberantly as their lips could bear. I do not yet understand, so I cannot yet fully express the reasons, but we felt a complete sense of freedom and love on those walks inside the barbed wire. It was as if the souls of those who died were handing over to us the feelings that were prematurely taken away from them, that they never got to use themselves. The gift of life was completely unexpected. Amy Hollowell, a writer for the International Herald Tribune, says that we discovered something here that is not written in books.

I would typically wake at 5, wait for the bell to ring at six (108 chimes), and attend a small group meeting at seven (before breakfast). I was fortunate in my group assignment; the leader was Peter Matthiessen, writer and Zen teacher, and to start the meetings Peter invoked an old Plains Indian tradition of holding hands silently in a circle until someone was moved to speak. Also in the group was a woman named Reza Leah Landman who dresses like a gypsy and bills herself as a Jewish nun. Reza Leah is an observant Jew who has studied many traditions, an intellectual who argues that there will be no healing until Christians understand that every Jew killed was another Christ crucified. Also in the group was a Polish woman, Marzena Rey, who exiled in Germany because of her activities as an organizer with Solidarity, and was permitted to return to Poland only three years ago. During the week, she repeatedly encouraged the Poles at the retreat to find their own voice; they seem to have developed habits of withdrawn silence after years of living under the Nazis followed by two generations under the Communists. And there was Eve

Marko, who managed the difficult task of being the primary organizer for the event and elegantly spare master of ceremonies, while at the same time addressing the emotional legacy of her own family, many of whom had been killed here. By the second day I found myself arguing vehemently about effective means to avert the recurrence of the history that surrounded us. My hot opinions may have done little but stir the morning air, but the act of putting down the camera and speaking up was very cathartic for this usually silent photographer. For the moment, our little morning discussion group became a family of immense intensity.

Everywhere you turned there was a conversation with a stranger who was going through a unique experience. I met two Europeans who told stories of being born of Jewish mothers and SS fathers, and I met several who, like myself, had parents who had never spoken of their was experiences, or who were not told they were of Jewish heritage until they were older. I entered this retreat thinking my own story was hardly worth mentioning next to those that involved more bloody horrors, but I learned that the scars on children of silence were deep, widespread, and well hidden. My mother, at age nineteen, escaped Vienna on the last train before the Anschluss 1938. She grew up in a long assimilated Austrian-Jewish family and was born with the instincts of a peacemaker-mediator. In the charged atmosphere of Vienna in the thirties, she tried to get her classmates—Jews, Catholics, and Protestants—together for constructive dialogue. She subsequently brought me up in a Massachusetts community of Congregational-Unitarian church where I was president of the “Pilgrim Fellowship”, and I was not aware of my Jewish roots until I was twenty. My parents’ values were molded by a life experience where such distinctions had brought catastrophic conflict that ended the world as they knew it. I spent several decades working through resentment about being “deceived” and readjusting to my new identity, but speaking with children of silence in Auschwitz I developed even more compassion for my mother, and others who had to cope with more extreme situations than hers.

I made a friend in Auschwitz who is a civil engineer in Berlin. His Jewish mother married a Gestapo officer whose connections had kept her family outside the gates of Theresienstadt, but, having to blend so completely into the countryside, the mother suffered a kind of schizophrenic split. Even now, she is completely unable to speak about her Jewish roots. If asked she says she doesn’t remember, and if pressed she breaks into tears.

About three days into the retreat, my dinner companion leaned over to whisper in my ear a politically incorrect question: “Peter, do you feel somehow happy here in Auschwitz?” We were both relieved to find we weren’t a long in experiencing an emotion we thought was impermissible in this criminal place. We can’t fell total horror 24 hours a day, and the vacuum that remains is filled by the full range of human emotions, but each one is greatly amplified. For this reason, Auschwitz becomes a very powerful and unpredictable place to spend an extended period of time. I think

the amplification of emotions occurs because one is forced to embrace and accept the interrupted lives—the trapped souls that are everywhere to be found—and integrate them into one’s consciousness. They are looking over your shoulder all the time, they demand that you pay attention, not just to them, but to your own life and mind. Perhaps it’s not an accident that they call this a “concentration camp”. Those souls lie in wait wielding huge kyusaku (Zen sticks), and when you are tempted to act selfishly or when you let your mind wander from the present moment, they immediately see, and they whack you hard on your shoulders: you feel a fool, but you wake up right away. On the other hand, when your concentration is complete, when you are fully alive in this place, you feel in some way that you are releasing these souls from their bondage. If not literally, then in the sense that you are breathing for them the breaths that they were never allowed to take. It is at once an inspiring opportunity and a heavy responsibility to breath or weep or smile or speak or just maintain silence on behalf of these spirits. This is a place of great intensity. It is a place for great sorrow and great joy, for great bitterness and great love. This mix of emotions was a complete surprise to me and to others in our group, yet I think this is why so many people have said that Auschwitz is a holy place, a place of pilgrimage and transformation.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.