I AM NOT A BUDDHIST. I don’t have the proper robes, I sometimes get confused during worship services in the zendos it has been my privilege to visit—yet, gate, gate, paragate,” I have been converted many tmes to Buddhism by experiences of its utter seriousness in practice and by its immense heritage of art. To say “I am not a Buddhist” seems tantamount to saying “I am not a human being”: an evident lie. One does not need to be formally Buddhist to recognize that the experience of great Buddhist Art is essentially a conversion. The quality of work of religious art may even, and properly, be assessed in terms of its power to convert. But to do so requires investigation of the meaning of conversion.

As Americans, we are more than likely to have a pop-culture “feel” for the word “conversion” that turns out, when one looks at these mental contents, to coexist with a deeper personal meaning. At the pop-culture level, there is a revival tent by a river somewhere in the Deep South of the mind, and passing that way one hears the impassioned voice of a preacher. That is one meaning of conversion, not the one I mean.

The conversion in contact with a great work of religious art is a shift in body, mind, and feeling that moves one almost involuntarily to conform with its spirit. If the work represents a human figure, for example a Buddha seated in meditation, and if the work is radiant, there can occur a general physical shift: back straightens, neck and head find their truer places in the stack, tensions become visible and drain down. The ancient work becomes a teacher: one’s mind resumes something of its nature as a grateful reflector of reality rather than a tea party at which the topic of discussion is life. One is gladdened by what one sees, whatever it is. The stone-carved jeweled necklace against the bare breast of a royal meditator—a perennial theme of Buddhist’ art—reminds one of the dazzle and profusion of our lives and of the emptiness against which all this is lived out. One receives both impressions with gratitude: this is so. The cut of a robe and its pattern of folds become, in the time of conversion, the ordered pattern of the world in which we are enfolded. One registers, with one’s sensitivity, everything, even the weight of the figure’s eyelids. One cannot help but experience one’s imperfection; while all this takes place, there are splats and vagrancies in the inner field. Yet consciousness has awakened.

In time the spell breaks, the conversion has occurred, one moves on. Religious art is not, nor can it be, the source of permanent conversion; it is a system of samples or tastes, providing a look forward or within. The intimate reorganization which it provides, and which it is meant to provide, is transient. The source of permanent conversion lies elsewhere, in fundamental practice and examined living, although the experience of great religious art secretly nourishes practice, and the making of religiously dedicated art can be an episode of examined living.

♦

In order to understand the nature of the Buddha image and its meaning for a Buddhist we must, to begin with, reconstruct its environment, trace its ancestry, and remodel our own personality. We must forget that we are looking at “art” in a museum, and see the image in its place in a Buddhist church or as part of a sculptured rock wall; and having seen it, receive it as an image of what we are ourselves potentially. Remember that we are pilgrims come from some great distance to see God; that what we see will depend upon ourselves. We are to see, not the likeness made by hands, but its transcendental archetype; we are to take part in a communion. . . . The image is of one Awakened; and for our awakening, who are still asleep. The objective methods of “science” will not suffice; there can be no understanding without assimilation; to understand is to have been born again.

—A. K. Coomaraswamy

There is the art-historical map of a tradition, and there is one’s own voyage across that map: often very different things. The first can be learned by the heirs of each tradition, and probably should be by more scholarly souls; the second is partly a matter of good luck—one had to be in New Delhi or Cleveland anyway. The first is well drawn and eminently rational: from these sources in the early stupas at Bharhut and Sanci, we can follow lines of influence through Gupta India and beyond in time and space, until we find ourselves in the enduringly Buddhist lands north and east of the Indian cradle, noting as we go hundreds of transformations and innovations in style and iconography, dozens of blendings between the migrant Buddhist vision and indigenous arts at every level of sophistication.

The second is not necessarily well drawn, nor even drawn to scale. Some small, impressive object may occupy a larger place in one’s memory than entire stupas listing with the weight of their wall reliefs. And there are almost certain to be gaps, works of acknowledged greatness that one hasn’t encountered even in books about such things. One’s personal map of Buddhist art is a pilgrim’s map, sketchy and awkward, but valid for its purpose.

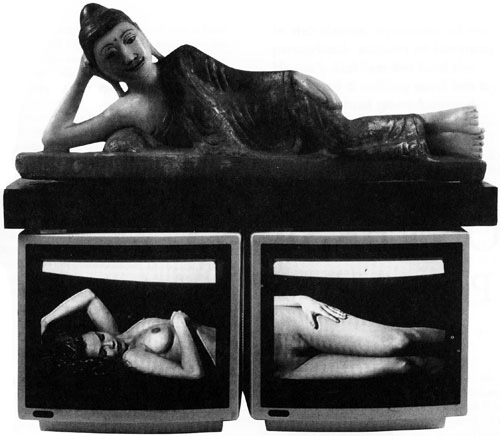

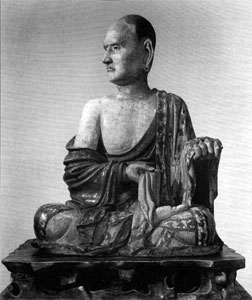

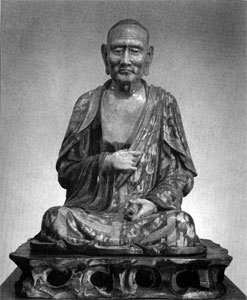

Figure of a lohan(left), and Seatedlohan(right) China, twelfth century C.E.

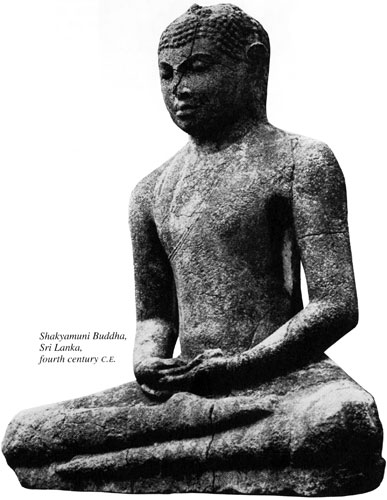

My own map began impromptu with the cover of the paperback edition of Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, which in the sixties had the impact of a calling card left by one who had gone beyond. The cover illustration was a dhyani (meditating) buddha from Sri Lanka, dating to the third or fourth century of our era. The photo credit was to Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, of whom I knew nothing. This image—and the sculpture itself, which I was fortunate to see some years ago—perpetuates what must be the spirit of early Buddhism. Free of all superfluity, the carving presents in simplest form the posture and attitude of meditation, and does so with such inward but tangible vitality that one senses the breathing person, the weight of limbs, the relaxation of tissues. To look at the image well is to feel complexity drop away, to experience remorse that one is still complex, to hear the call to simplicity. To look well is to recover a feeling for essentials. One scans this carving in vain for attributes, personal markers; there are none, as there are none finally in ourselves.

♦

An eleventh-century comment on a ninth-century image:

The Great Compassionate Avalokiteshvara . . . a painted icon, is the work of Fan Ch’iung . . . Although its hands and arms are so numerous, they balance each other on left and right in accord with the conception. In its complexity it is Heaven’s design, and one sees nothing in excess. Each of the various attributes is rendered to perfection. The brush strokes are like wire, but have an exquisite strength and warmth, carrying out the minutest details to a wondrous perfection.

Works of art cannot confer realization, but they can provide evidence of accomplishment and in this way encourage both newcomers and discouraged veterans. Buddhist art is prodigiously rich in such evidence, conveyed in some instances with solemnity, in others with a smile. My own experience at these poles of expression ranges from a set of severe twelfth-century Chinese lohans (immediate disciples of the historical Buddha) in various museums across the world to the brush portraits of Ch’an and Zen patriarchs and monks, filled with unorthodox gaiety.

The pair of life-size ceramic lohans in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, has inspired generations of seekers. When the museum staff routinely took the pair off exhibition some years ago during gallery renovations, they were surprised by a steady stream of inquiries—and privately wondered, I believe, whether the figures were somehow the focal objects of a cult. No photograph can convey the powerful presence of the lohans: the younger man subtly arrogant and distant, as if pausing impatiently in his exercises—have we interrupted him?; the older man with a deep bony face, warm eyes, and a receptive expression, looking toward us with compassion from an earlier epoch of religious striving. Each dwells tangibly with himself, yet connects. Their atmosphere is stronger than one’s own. Before these figures, one knows that one has come upon true religious seekers, uncannily present works of art, yes, but art at a surpassing level.

They are part of an ensemble, originally perhaps eighteen figures, collected in about 1912 from an abandoned cave sanctuary in China. Several other complete figures have survived, notably one now in Philadelphia at the University Museum, another in the British Museum, London: the figure in Philadelphia open, vigorous, strangely heroic; the one in London severe, of royal presence. Were the artists who collaborated on these works interested in exploring—and projecting—a “typology” of spiritual seekers? So it seems; such is the impact. All of these types and attitudes are admissible, even necessary. And the lesson is not altogether lost on one.

Brush-drawn images of Ch’an and Zen adepts, exemplified by the monk Feng-kan napping with his pet tiger, represent another pole of the genius of Buddhist art. The image is marvelously droll and informal, with zinging brush strokes and offbeat characterization. And yet it confronts us with some of the central ideals of Buddhist practice, implicitly invites us to persevere to the point that all persevering ceases, all strain concludes: to sleep, in that anticipated time, is no different than to wake, and one’s tiger is affable.

♦

For a work to be truly alive, each of the thousand hairs of the brush must be energized.

—A calligrapher’s proverb

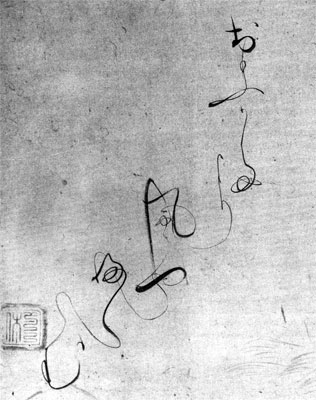

Even in this very brief exploration of the map of Buddhist art, we cannot afford to overlook one of its most eloquent expressions: calligraphy. For example, the rendering by Ikkyu Sojun, famed fifteenth-century monk and abbot, of nostalgic lines from The Tale of Genji is an indescribable masterpiece. “Do they have me in mind? The wind seems to bring news of their thoughts.” The incredibly musical flow of his line across the surface, its rhythmic appearances and near-disappearances, its utter security although it has so little substance—all of this and more brings one to sense, in the calligraphy and within oneself, an energetic condition that surely approaches the essence and magic of Buddhism. One is converted, again; now not by the majestic figure of an awakened human being but by the trace of a gesture.

An eighth-century Chinese painter answers a question about his technique: “Externally, all Creation is my master. Internally, I have found the mind’s resources.”

Feng-kan sleeping on his tiger, in the style of Shin-k’o, thirteenth century C.E., ink on paper

The Buddhist heritage in art inspires practice even today and not only among those formally dedicated to Buddhism. But this observation raises an engaging question: does the heritage inspire American Buddhist artists in their vocation as artists no less than in their vocation as seekers of truth? American Buddhist artists, and their witnesses, may worry at times about their dual heritage, their belatedness, and—not least—the question of authenticity. The dual heritage is both confusing and potentially enriching. To be Western and American is to be Jewish and Christian and Socratic, and imbued, like Rembrandt, with regard for the individual; it is to be devoted to science and warily grateful for technology; it is to be far more familiar with Jackson Pollock’s calligraphy than with Ikkyu’s, and to prefer one’s tea without butter. To be Buddhist is to recognize as one’s own an Asian tradition that rarely intersected with the West until the early nineteenth century and remained “other” and alien until quite recently. Apart from this relatively external sense of cultural belonging, to be Buddhist surely means to engage seriously with inner disciplines that can lead into the depths of human nature and uncover an “order of things”—perceptions of reality and a sense of purpose—that change one’s life in large and small ways.

This dual heritage can strike the artist as uncomfortable—as can the obvious fact that artists, like the rest of us, are latecomers to Buddhist tradition. The Wheel of the Law has been turning for some time without much assistance from us, so far as we know, and the heritage of visual art, scripture, liturgy, and instruction is overwhelming in scope and profundity. Can a Western Buddhist artist of our time make a single gesture that has not been made elsewhere, elsewhen, with an authority one cannot hope to match?

WITH THIS THOUGHT the adventure begins. It is a crippling thought. When one sets it aside, two rather different paths become evident. On the one hand, it is possible to declare summarily—either in words or by unspoken assertion—that because one is a Buddhist, one’s art is Buddhist. To do so may be to adapt that odious, mainstream American, relativistic assertion, “Art is what artists do,” to read: “Buddhist art is what Buddhist artists do.” Or, on the contrary, for some artists in whom the spirit of Buddhism runs deep, the assertion may be factual. On the other hand, it is possible, and probably more realistic, to bend the knee and serve a long apprenticeship, which, like any apprenticeship, guarantees opportunities for effort and learning but does not guarantee results.

Ikkyu Sojun, fifteenth century C.E., ink on paper

It would be an apprenticeship to the tradition: to its forms and at least some techniques, to its meanings, to its high standards, to its history, to its variety, to its symbols and sensibility. And because the apprenticeship is a retrospective search for roots, and for sap with a certain aroma, it leaves unanswered the central question of what meanings the artist today needs to express, and through what forms. Apprenticeship raises this question to a peak of tension and un-answeredness, yet lets it be until the time is ripe to begin answering it. The question only sharpens as one experiences the greatness of past accomplishments, and as one measures the distance between their language—the language of those who came before—and our own. At the worst of times, the apprentice to tradition will feel that the gap is unbridgeable, that we neither can nor should create Buddhist icons now as they did then, nor are we likely to develop authentically Buddhist art in the languages of modern and postmodern art.

All of this is an enactment in the spirit of the Fire Sermon:

All things,

O Bhikkhus,

are on fire.

The eye,

O Bhikkhus,

is on fire;

forms are on fire. . .

The fire purifies. It need not burn away the longing to act in the world as an artist, to make images that are true and new and moving.

From the fire can emerge a Buddhist artist. It does not necessarily mean to adapt or copy past models, although there is always a niche, particularly to liturgical purpose, for strictly traditional artistry—for the thangka maker and bronze-worker who create time-honored images along time-honored lines. It does mean to accept as one’s intimate heritage the standards embodied in great works of the past. It means to strive to meet and—why not?—surpass those standards in works that reflect our current experience and enrich it.

To live the artist’s vocation in this way is the conversion of the artist. It is also a mystery, for who has seen contemporary art that arises from knowing love of the tradition and natural, American fluency in our own visual languages?

I REMEMBER a Japanese lacquer box. Its lid is black and gold, the colors of darkness and light. It has a pictorial decoration: a torrent of water with wagon wheels bobbing chaotically in the flood, some half-visible, others almost completely immersed. The water swirls like hanks of thick cord. In contact with this work, the mind fills with two simultaneous images. The first is of a village flood in spring: the peasants’ carts have broken up, the wheels tumble downstream. The second is the Dharma Wheel, in its regularity and dignity, rushing down the samsaric stream of time and events, half-drowned, half-visible, half-invisible. What will become of it?

Editor and biographer of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Roger Lipsey most recently published An Art of Our Own: The Spiritual in Twentieth Century Art. He is currently working on a reinterpretation of the Delphic oracle for HarperSanFrancisco.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.