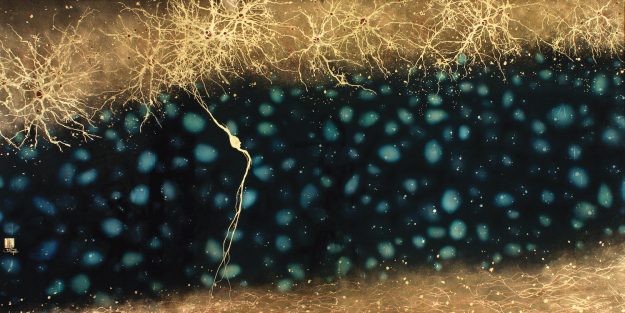

If you’ve perused the current issue of Tricycle, you’ll have seen the beautiful and intricate artwork that illustrates our article about the convergence of Buddhism and neuroscience, “A Gray Matter,” by Columbia University professor of Japanese religion Bernard Faure. If these images seem hauntingly familiar, it’s for a reason. They’re of the neurons in our brains! The artist behind them, Greg Dunn, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a doctorate in neuroscience last year. Since then, he’s been focusing on painting in his easily identifiable style: a modern, science-based twist on the ancient East Asian brush painting technique of sumi-e. Like the Buddhist monks who first practiced sumi-e, Dunn grounds the creation of his art in meditative practice—a sumi-e painting, as Dunn and many others before him have pointed out, is a reflection of the artist’s internal state.

Dunn’s artwork was like nothing the Tricycle editors had seen before, and we were curious to find out exactly how he did it. Tricycle’s Alex Caring-Lobel and Emma Varvaloucas caught up with Dunn via email last month to find out more about the neuro-painter’s creative process.

What initially drew you to the field of neurology? What then drew you to art (in general and to painting neurons in particular)? When I was trying to figure out what direction I wanted to take my life, I always struggled to whittle down what I was very interested in from what I was truly passionate about. Over time, I came to realize that every one of my interests had a neurological story to it. We are unable to experience anything—our thoughts, emotions, senses, interactions with others—without the brain. Since the workings of the brain pose some of the greatest mysteries of the universe, I thought that neuroscience would provide me with a fascinating, refreshing, and productive field of study.

I expanded my artistic output when I was in graduate school as a means to fulfill my need for creative expression, as well as a way to rescue myself from the frustrations of laboratory experimentation. I don’t think the general public has a clue how difficult bench science can be—how much time, deep thought, passion, and persistence it takes to come up with an answer to a basic biological question. There are so many variables at play that oftentimes one’s best efforts result in repeatedly failed experiments. It can be truly harrowing.

Painting allowed me respite from these frustrations because it gave me a sense of control. When I paint, I am far less subject to frustrating constraints and uncontrollable variables. I am free to manifest the images in my mind and make them known to the rest of the world; the principal boundaries are the limits of my creativity. For me, it is an excellent environment to grow spiritually. I am deeply grateful that my interests in Asian art, in particular Chinese and Japanese sumi-e, combined seamlessly with my interests in neuroscience and meditation. I have learned that it is through combining their passions in novel ways that a person can contribute something unique to the world.

Neurons by their very nature have a Zen quality to them in their spontaneous, random branching patterns, and many years of neuroscience lectures were filled with inspiring images of stunning neural landscapes. Though they are too small to see with the naked eye, neurons are as much a part of nature and as worthy a subject for artistic expression as the traditional themes of sumi-e—trees, branches, flowers, etc. By painting them in the Asian aesthetic, I am making the declaration that neurons fit squarely into the canon of Asian art because they are representative of forms that are consistent across vastly different scales in nature.

What is it about the style of sumi-e that appeals to you? How did you learn how to do it? Sumi-e doesn’t dawdle or disguise itself. It cuts directly to the core of the subject, eliminates superfluous detail, and allows you the breathing room in carefully designed negative space to fully express the nature of the object. Despite its seeming simplicity, it is a skill that takes years, even a lifetime, to master. The medium is utterly unforgiving, requiring concentrated calmness to bring each stroke to perfection. Sumi-e practice goes hand in hand with meditation and spiritual practice, and I love that the strokes of a master are a direct reflection of their clear state of mind. Sumi-e is a perfect medium through which the artist can communicate their internal state.

Sumi-e’s earliest practitioners were highly disciplined Buddhist monks who meditated in preparation for painting. Have you taken on similar practices to prepare? If so, what are they? Absolutely. Meditation practice serves a powerful dual purpose in painting as it does in any creative endeavor. First, inspiration naturally arises of its own accord from a calm mind in meditation. Second, meditation is critical in bringing the practitioner closer to the calm natural state from which spontaneity, self-confidence, and flow originate.

I maintain a regular practice of meditation, and I also own a sensory deprivation tank that is very helpful to me. Though it is my goal to meditate prior to any important step in the creation of a painting, this is not always a reality! Oftentimes, I get caught up in the passionate, scattered mania that is the creative process. This mania drives a compulsiveness to continue painting even though I intuitively know that I’d be better off after a meditation break. Though it often feels good, for me this compulsive state is an obstacle because it simply doesn’t result in good paintings. I very seldom speak in absolutes, but I can unequivocally say that I paint better after meditation, every single time. The same war that every practitioner fights between their intention to keep their mind under control and the mind’s intention to do whatever the hell it wants certainly applies to matters of creativity!

What kind of deliberate techniques do you employ to achieve the effect of randomness and spontaneity in your paintings? What do you make of this relationship between the deliberate and the spontaneous in your work? The brain is a pattern detector. It readily extracts order from chaos, but does not easily generate chaos from order. You will find, if you experiment, that when you attempt to generate random numbers, draw a line that branches in random directions, etc., that you will soon adhere to unconscious rules that govern patterns underlying your attempts at randomness.

To help with this, I outsource much of my spontaneity generation to similar forces that govern the growth of neurons in the first place. By accident, I discovered that under certain conditions, ink blown across paper will branch outwards in beautifully random directions. The reason for this is that subtle fluctuations in the flow of air, fiber orientation, or changes in absorptivity in the paper, etc., will cause the ink beads to split up and branch in different directions that represent the path of least resistance to flow. This is exactly how a neuronal axon or dendrite grows outward from the cell body—it encounters many objects in its path, and through following the path of least resistance around them, carves a randomly branching pattern through the extracellular matrix. You find this pattern in trees, vines, cracks in stone, paint peeling off of a metal surface, a lightning bolt—and incredibly, even in the orientations of galactic superclusters! This random branching pattern is prevalent across wildly different scales, and is what I like to call a “fractal solution to the universe.”

The real beauty of this painting technique lies specifically in the artful balance between inviting in unpredictable spontaneity and deliberately corralling it. Here, the parallels with meditation are substantial. In meditation, continuously dividing the infinitesimally thin line between effort and non-effort provides the surest route to the natural state of non-dual awareness. In painting, it is a similar balance in allowing randomness to occur while orchestrating it within certain boundaries. This spiritual practice of learning to balance effort and relaxation of control draws a final, wonderful parallel to meditation in that it takes place through control of the breath through the blowing technique.

Some might think that science and art are not necessarily compatible. Why do you think that in the case of your work, they complement each other so well? Science and art are born of the same human instinct to communicate our experiences to one another. As we have a sex drive that underlies our desire to influence the world through our genes, we also have a drive that underlies our desire to influence those around us through our ideas. Sharing our ideas is the basis of our scientific and artistic culture, and it is of basic importance to our survival as a species.

Art and science are at the poles of the spectrum of how humans are creative. Science is the creative drive applied to describing aspects of consensus reality, and art is the creative drive applied to describing aspects of subjective reality. The bedrock of science is that two people of drastically opposed opinions should be able to perform the exact same experiment and get the same answer. In this way, it is my opinion that photorealistic painting is more of a science experiment than it is an artistic one, because different artists of comparable technical skill will reference consensus reality in order to create identical paintings. This would not be the case if you were to ask those same artists to paint an abstract landscape because they would each be referencing their unique, subjective personal experiences to inform the artwork. Of course, each new piece of music or science experiment lies somewhere on the spectrum of art/science innovation depending on the extent to which the new creative endeavor attempts to describe consensus vs. subjective reality. Art translates our subjective experiences into consensus reality for others to appreciate, whereas science uncovers aspects of reality that have always existed and will always continue to exist. They are both born of our desire to create, experiment, and share our results with one another.

The human brain appears to be hardwired to find spontaneous, random branching patterns beautiful. This has been an observation of Eastern artists for centuries, so much so that it is my belief that through artistic innovation they have scientifically proven something about how the brain appreciates aesthetics. To insert neurons into the tradition of Asian art makes sense, and I think my artwork has been successful because it plugs an artistic innovation, painting neurons in a stylized way, into the fleshed-out ground of Asian art. I strive to anchor my art in some of the principles that the geniuses before me have discovered, but to give it my own subjective twist that takes it in a new direction. Respect the old and search for the new.

Tell us something surprising about the brain that someone who hasn’t studied neurology wouldn’t know. And then tell us something surprising about you! One very interesting aspect of how our brains work is that our sensory perceptions are deeply influenced by our emotions. In the visual system, for example, there is a very complicated cascade of processing events that occurs between when light hits the retina and when we “see” a completed image. Many steps of rudimentary data processing occur that address aspects of vision such as form, color, contrast, spatial orientation, and resolution. Interestingly, these initial streams of information are sent to the limbic system, the system of the brain that processes emotion and memory, prior to the perception of the image being completed. From this roughly processed data, the limbic system will add emotional inflection to the sensory data, distorting our “objective” view of what we are looking at. This is an unconscious process, and can result in scenarios wherein we are looking at a hose but see a snake because we may have a deeply rooted fear of snakes and our amygdala has added data into our visual stream. Our emotions and unconscious mind are constantly coloring our perceptions. This scientific fact gives interesting insight into the spiritual practice of trying to see the world for what it is, rather than for what we ascribe to it through our mind’s tendency to grasp or avoid.

As for something surprising about me—I’m married to a Bulgarian, and have been learning Bulgarian mostly on my own for the past few years. To put it lightly, it has been a thoroughly humbling process. I’ve been amazed at how complex it is to learn a new language as an adult, particularly one that has very little in common with your native tongue. It is by far the most complicated skill I’ve embarked on in my adult life, and when we are traveling in Bulgaria my mind is working fifty times faster than normal all day every day. Great for my brain but not so great for my ego, which, in the end, is actually good for everybody!

One of my favorite paintings is “Cortex in Metallic Pastels.” This painting is of the layered structure of cerebral cortex, a classic neuroscience image.

The first order of business is always to work out the basic blocking of the image by doing rough mockups in Photoshop. This is the foundation of the painting, and the forms must work in silhouette or the painting will never work as a finished image. Here I try to build in contrast in line quality, neural architecture, and complexity.

Once the basic layout is satisfactory, I move on to color, metal selection, and reflective design. These are secondary attributes that are also important to the finished painting, but are mere enhancements when compared to the blocking. Through deciding which types of neurons will be in gold and which in ink, enamel, or mica, I can create contrast and hopefully build in visual interest.

Once I’m happy with the rough Photoshop version of the painting, I will begin the actual painting itself. I prefer to separate the days of designing the painting and actually painting it, because this enables me to work without hesitation because I know the end result of what I’m going for beforehand. The painting then becomes a complex technical exercise, allowing me to focus on technique more directly and giving me space to really concentrate on the task at hand without the perpetual chatter and worry about the broad creative design in the back of my head.

This painting utilizes techniques in reflectivity modulation of gold leaf, transparent dye application, clearcoat sealing, and canvas preparations to enable the blowing techniques I previously mentioned on metal, metal powder application, etc. I won’t bore you with the details of a lot of this, but the type of painting I do is very gratifying to me because it draws heavily on my knowledge of chemistry and physics. My studio is simultaneously a place for creative brainstorming and lab experiments.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.