Too Liberal

Several issues ago Professor Robert Thurman outlined his view of Buddhist politics in “The Politics of Enlightenment” (Vol. II, No.1), which was a clear example of what I perceive to be a bias in your magazine and the Western Buddhist press in general. It seems that we are being led to believe that politically, socially, and economically Buddhism equals liberalism. It’s difficult for me to accept Professor Thurman’s idea of “welfarism,” a term he apparently feels will be less objectionable to your readers than “socialism.” I don’t presume to question the Professor’s erudition, and he certainly is entitled to his opinion, but I find it impossible to reconcile his idea that “every living being in society is owed a livelihood” with my own limited understanding of the dharma. Firstly, it is unclear to me who owes this and to whom it is owed. Do individuals fall into both categories simultaneously, or are we making a distinction here between two classes of people in society? Secondly, does this line of reasoning lead to the conclusion that capitalistic or “conservative” views are opposed to the teachings of the Buddha? I suspect that what many Westerners find attractive about Buddhism is the concept of karma, which places responsibility for our actions squarely on our own shoulders and makes “destiny” something that we create for ourselves at every moment. The idea that as individuals we are somehow “owed a livelihood” does not seem consistent with this.

I would guess that many Buddhists in this country came of age in the liberal sixties and I am willing to concede that many, maybe even most, Western Buddhists consider themselves liberals. It seems to me, however, that the inherent connection between Buddhism and liberalism is more apparent than real.

I find Tricycle consistently engaging, and “The Politics of Enlightenment” was no exception, but I think your readers would be better served if you ran more articles with a less liberal bias.

Herb Gatti,

Wakefield, Massachusetts

Bag the Polybag

My friend gave me a subscription. I will not renew unless you stop the plastic! Yes! I am willing to receive it damaged, etc. NO PLASTIC PLEASE!

Susan Weed,

Saugerties, New York

Love the magazine. . . but what’s with the plastic wrapping? Landfills don’t need it nor do I.

Moira Voss,

New York City

Tricycle Responds:

Okay, dear readers, you win. We tried mailing magazines without wrapping and you complained of damaged covers; we tried kraft-wrapping (brown paper sleeves) and you complained that the wrapping arrived sans magazine; on sound advice that there is no difference between the biodegradable capacity of high-cornstarch polybags (the kind we used) and kraft-wrap, we tried that. Now, as a result of letters like these, with this issue we are trying envelopes—the most expensive method available. If you would like to help us offset this expense and/or join our efforts to replant trees to compensate for paper use, you may send checks payable to Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, 163 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011.

Race Matters

I applaud the last issue (Vol. II, No.4) for having so much material on people of color. From South Africa to the internment camps for Japanese-Americans and Norman Fischer’s article on racism, this issue reached way beyond “white Buddhism.” Even the article on Bernardo Bertolucci’s movie investigated the views of Asian Buddhists.

I know that many Asian-American Buddhists are not interested in your contemporary way of presenting Buddhism. I happen to love your magazine even though my own family has no interest in it. I am happy when it combines different worlds.

Joyce Chung,

Chicago, lllinois

Your last issue smacked of political correctness. I hope you are not buckling to the fascistic forces that want to make everything look like it was sponsored by a United Nations council. What is best about Tricycle has always been its sincerity about the dharma and clarity of vision. To sacrifice this to the secular values of multiculturalism is to pay too high a price.

Matthew Rice,

Eugene, Oregon

A comment on the article “Buddhism, Racism, and Jazz” in the Summer Issue (Vol. II, No.4).

African-Americans don’t need you.

Mr. Fischer would make a great sociologist but what is a Zen man doing whining about why blacks are not involved in Buddhism. Why should Afro-Americans come to a white roshi who probably is unqualified to teach the dharma or even lead the way?

Many black people are masters of martial arts, and enjoy experiences similar to the kind that are produced in Buddhist practice. Also, just because you don’t see them, there may be black Buddhist practitioners.

The point is Afro-Americans will find their salvation when and where they wish. They do not need a bunch of evangelistic American roshis looking for more clients to help them. The understanding America needs is the understanding of enlightenment as taught by the Buddha. His teachings transcend all racial problems and proper practice could do the same for America. Buddhism is an individual practice and unless, Mr. Fischer, you have become a bodhisattva, sit down, shut up, and “work out your salvation with diligence.”

Harold T. Reid,

Ferndale, Michigan

I am grateful to Norman Fischer for sharing his thoughts about race and American Buddhism, race and American society. They are mostly on the mark, but there are several key places where I think his analysis moves away from past and present reality.

Most immediately, it seems to me that even in his sincere wish for inclusion, people of color—African-Americans, Asians, Latinos—are rendered invisible again, if only for the sake of making a larger point. Fischer describes “looking around and noticing that there are no dark faces in the meditation halls. . .” I practice in several of the same Bay Area communities, and looking around the zendo day to day, week to week, I see such faces steadily coming to zazen, lecture, classes, community gatherings. Certainly the numbers are small, but their practice and spirit of inquiry are strong. If “white” teachers say they see only “white” people, is anyone else who is actually there likely to feel welcome and come back? Can we strike through the veils covering our own eyes and acknowledge each person’s presence? To do any less causes pain and reinforces the unthinking power of white Americans.

This brings me to a second point. “African-Americans from slavery times until World War II carried this suffering in secret.” Is this true? I would suggest that there have always been those who would speak the truth loudly, and the price they paid (and continue to pay) is trivialization, repression, even death. I think this secret is fundamentally kept by white societies—American and European—whose domination was/is based on power and violence, who for reasons of greed, hatred, and delusion ignore their true minds’ message that all beings wish and deserve happiness.

Alan Senauke,

Berkeley, California

(Alan Senauke is the national coordinator of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship.)

Chay: Pro & Con

In some respects I agree with the letter written by Aki Sann Chay in the Summer ’93 Issue (Vol II, No.4). Personally, I would like in-depth biographies and teachings from realized teachers of all traditions, not dilettantes who have had a passing experience with Zen on an intensive weekend or the like.

The reason I find John Cage offensive in conjunction with the dharma is that he took the universal of listening to the sound of “silence,” e.g. mindfulness, made it into a performance form, and took credit for it to aggrandize his own ego as a composer. I would hope that a moment of mindfulness might bring someone toward the Path, but feel that wisdom and compassion still must be taught by a proper teacher.

Christine Zachary,

Portland, Oregon

In response to Aki Sann Chay’s letter: I hope you read Kerouac’s Wake Up in the last issue (Vol. II, No.4) to see that the light of the Buddha’s dharma obviously touched Kerouac as truthfully as it touched you or me or Ginsberg or Trungpa. That impulse towards wakefulness should not be discouraged or rejected from anyone, be they saint, sinner, male, female, orthodox, nonaligned, dead, or alive. If I may borrow from Kalu Rinpoche, this is “the Dharma that illuminates all beings impartially like the light of the sun and the moon.” It is undeniable that the Buddha is in all of us.

Alan K. Anderson

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Transplanting Karma

The article by Karma Lekshe Tsomo on organ transplants made me stop and re-evaluate long-held attitudes.

I started working in hospitals shortly after I became Buddhist, over half my middle-aged life ago. Although it is not my specialty, I have dealt with transplant recipients and donors over the years. Like most of the Buddhists the author interviewed, I too have felt that offering my body parts for other’s benefit after my death would be a truly compassionate and meritorious act. My driver’s license lists me as both an organ and tissue donor.

First, a word about tissue donation: major transplants certainly get all the press, but much of the body is reusable. The cornea of the eye, skin, bone, blood vessels, heart valves, the coverings of the brain (dura mater), and muscles (fascia) are all transplantable. This tissue is treated, frozen, and kept in storage for later use as grafts. For that matter, blood transfusions can be considered a kind of graft or transplant, as blood is technically a tissue (and you don’t have to die to give!). If one donates one’s body for organ and tissue harvest, numerous people could benefit from these gifts. Also, if tissue alone is harvested, there is not quite the rush to collect it as with organs. However, the three days of repose the author mentions would probably leave little tissue still usable for grafting.

The other issue I’d like to address is more speculative. Organ transplant recipients fairly routinely experience “hallucinations” during the early phases of their recovery. This is attributed to the initially high doses of corticosteroid drugs given as part of the immunosupression regimen to prevent organ rejection. I took care of one heart-lung recipient, however, who reported a particularly realistic vision. He was able to identify the donor, a young woman who had been murdered, and he claimed to have actually seen the shooting as it happened to her! Since donor anonymity is one of the basic ethics of organ transplantation, and since this patient had been whisked to the hospital prior to the murder’s news release, one wonders if the “cellular memory” theories of the sixties psychedelic researchers might have some validity. If memories are transplanted with major organs, is some karma also? What kind of karma would pass from a murder victim? Conversely, if one led a meritorious life and donated one’s organs, would some of this merit transfer to the organ recipient as an additional gift?

Obviously the issue of organ donation is not as straightforward as it may have once seemed and deserves closer thought and study. For myself, however, my driver’s license will remain the same for the foreseeable future.

John Brinduse, R.N.

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Historical Nonduality

Just recently I was reading The Buddhist Handbook (Inner Traditions International), a history of Buddhism by John Snelling, which seems to contradict something in Keith Dowman’s article “Himalayan Intrigue” (Vol. II, No. 2) which states that the new Gyalwa Karmapa inherits from predecessors who were spiritual guides to Kublai Khan and successive Chinese emperors, and that they had been “the virtual rulers of Tibet before the Dalai Lamas,”

According to Mr. Snelling, however, it was actually the head of the Sakya School of Tibetan Buddhism (whose title is Sakya Trizin) who advised Kublai Khan and the Mongol emperors. As a result, says Mr. Snelling, that school “was the first to rise to political power in Tibet,” According to the book, the Kannapa leads the Kagyu School, whose members believe he can choose his reincarnation. The Sakya leadership, on the other hand, is passed on hereditarily from uncle to nephew. I would be interested to know which account is correct.

Anne Schwimmer,

New York, New York

(Tricycle asked Tibetologist John Dunne to respond.) Both accounts are correct! The Sakyas were the first sect to develop a relationship with the Mongols, and in Kublai Khan’s court, no lama could match the influences of Pagpa (1235-1280), the head lama of Sakya. All the same, Kublai Khan also looked to Karma Pagshii, the Second Karmapa, for spiritual guidance. Gradually, Sakya influence declined, and by the time of the third Karmapa, Rang jung Dorje (1284-1338), the Karmapa lamas held even greater sway than the Sakyas. After the fall of the Mongols dynasty, the Karmapas found themselves embroiled in numerous struggles for power in central Tibet. Eventually, the Rinpungas, lay disciples of the Kannapas, gained the upper hand (circa 1500). They and the later Tsang “kings” controlled most of central Tibet under the guidance of the Karmapas until the Gelukpas, led by the fifth Dalai Lama (1617-1682), finally wrested power from their hands.

In other words, the Sakyas advised the Mongol emperors, but the Karmapas did too. The Karmapas ruled Tibet before the Dalai Lamas, and the Sakyas ruled before both the Dalai Lamas and the Kannapas.

The Karmapa is said to reincarnate, and this sometimes leads to the differences of opinion that Keith Dowman reported. The Sakya Trizin (“Throne Holder”) comes from one of the two surviving houses of the Sakya aristocracy; he is often, but not necessarily, the nephew of the previous Trizin. He is not a reincarnated lama, but most Tibetans consider him to be just as holy.

John Dunne

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Taking the High Seat

The letter from Judith Crane and Jim Stone (Vol. II, No.3) prompted this response.

“Buddhism is pro-life” is a simplistic statement for complex and difficult times. The truth is that we experience suffering.

Who suffers more, an unborn fetus, a woman who makes a difficult decision to have an abortion, or those of us who impose our views on others? The question is obviously irrelevant. The truth is suffering. You can call it posturing or whatever you like—but sitting, even on a high horse, must be done with a good seat and an open heart. Which means respecting the horse, respecting yourself, and respecting others to make their own decisions for their own lives.

Ann Bodnar

Kansas City, Missouri

On the Trail

The haunting photo on the cover of your Summer 1992 Issue (Vol. I, No.4) inspired us to visit that site, Kyaik-tyo Pagoda, in Burma last November. Now the Buddha footprint on the Winter 1992 Issue (Vol. II, No.2) continues to intrigue us. Where do we find it?

Wendy Mickle

Lopez, Washington

Tricycle Responds: This altar is in Bodhgaya, India, which is ninety kilometers south of Patna and is the place where Shakyamuni is said to have reached enlightenment.

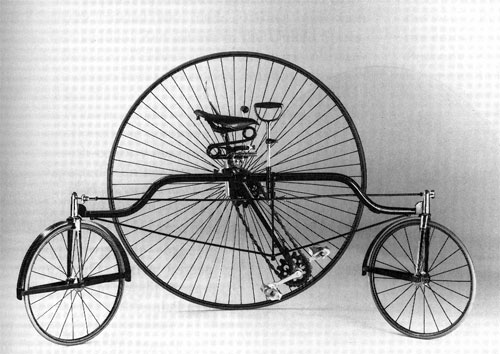

Tricycle on Tricycle

I certainly enjoy your publication. Please tell me, why is it called “Tricycle”?

Mark Caldwell

Phoenix, Arizona

Tricycle Responds:

The essential components of a tricycle—three, vehicle, and wheel—correspond to concepts found throughout Buddhist history. We speak of the three treasures: the Buddha, dharma, sangha; of turning the wheel of dharma; and of the three great vehicles of Buddhism: Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. (And while there is no traditional concept that parallels handlebars, the Dalai Lama, on being presented with a small golden tricycle, took hold of each one and said, “the absolute and the relative.”) What also influenced the choice of name is the Zen expression “beginner’s mind.” It implies a mind that is open, available, not constrained by habitual mental patterns.

Where’s the Beef?

With interest I read the different statements on eating meat (“What Does Being a Buddhist Mean to You?” Vol. II, No.2): they cover a wide spectrum of opinions. One important aspect, however, has not been touched upon at all: today’s methods of raising animals. How is it possible that out of ten intelligent, mindful, and caring people, not a single one mentions the extremely brutal reality of modern meat production?

Factory farms are hell realms for billions of suffering beings. This is something that did not exist in Buddha’s lifetime or even fifty years ago, and, it looks like, still doesn’t exist in most people’s minds. Can we honestly claim to be concerned with the suffering in this world while not only overlooking but—with our food choices—directly supporting this large-scale, institutionalized abuse?

Today, it’s not primarily a question of eating meat. The traditional arguments like honoring the spirit of the animal you kill, saying grace, or being mindful of the fact that life is eating and beings being eaten are all very well, and I can appreciate them, as long as you know how your meat was treated when it was still alive and feeling.

The extremity of the oppression, and the resulting suffering, is little known, even among clear-eyed Buddhists, especially among Tibetan and Japanese teachers.

Vajna Palmers

Lucerne, Switzerland

Wide, Wider, Widest

Your articles offer a wide range of Buddhist philosophy, history, and practices, as well as many diverse points of view on those same subjects. What a delightful change Tricycle is from the overwhelming number of magazines that are so insubstantial that they can be quickly paged through in one sitting!

In all of the diversity you offer, however, I have yet to see anything on Japanese Vajrayana Buddhism. It would be very enjoyable to see an article on Tendai Mikkyo Buddhism in your magazine.

Jo Pagliassotti

Germantown, Ohio

Silver Lining

A friend’s gift subscription to Tricycle last year was fraught with tension because she was trying to help create understanding between me and my oldest daughter, who has been a Buddhist nun living in Sri Lanka. My inability to comprehend her life, her decisions, and what I continue to feel is a rejection of the religious and family values with which she was raised has caused much anguish in our family. I searched the pages of your magazine for understanding in vain until I read “A Journey with Elsa Cloud” by Leila Hadley.

It was a tremendous comfort to feel another mother trying to come to terms with a daughter lost to the East. In time maybe I too will be invited for a visit and maybe now I will be able to accept.

Name withheld upon request

Zen Pillar

I am sure that I am typical of someone whose life was changed by Three Pillars of Zen edited by Philip Kapleau. Influenced by this book, I went to study Zen at Tassajara. That was many years ago, almost another lifetime. I stopped sitting, moved, married, switched jobs, etc. I lost track of Zen, lost track of myself—to tell the truth. Coming across Tricycle on a news-rack, I bought it to read the Kapleau interview. Halfway through reading it, I burst into tears, having realized that this man, now old, just stuck with it. My admiration for his resolve and understanding knows no bounds.

Jim Harding

Berwick, Pennsylvania

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.