Buddhism with Belief

Stephen Batchelor’s argument that the Buddha was a secular agnostic, denying knowledge of such questions as what happens after death, is based on two points: (1) a quotation from the texts in which the Buddha states that he taught nothing but dukkha and the ending of dukkha, and (2) an assertion that the Buddha would have approved of T. H. Huxley’s principles “Follow your reason as far as it will take you” and “Do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated and not demonstrable.”

As for the first point, Batchelor gives an existential slant to the Buddha’s statement by translating dukkha as “anguish,” but a quick look around the texts will show that the standard definition of dukkha includes “rebirth,” and that the path to the end of dukkha begins with the belief that good and evil karma bear fruit, that there is a life after death, and that there are meditators who have directly known these facts for themselves. These are hardly agnostic positions.

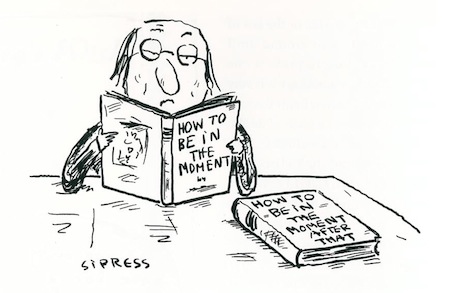

As for the second point, there are many passages in the texts where the Buddha speaks derisively of doctrines “hammered out on the anvil of logic,” and where he makes the point that nirvana, the whole point of his teaching, is beyond the sphere of logical inference. Nirvana can be demonstrated – in fact, directly experienced – but only by putting into practice certain working hypotheses that few agnostics would be willing to hazard. The statement that “the dharma is not something to believe in but something to do” makes a specious point, for it is impossible to act without accepting at least some things on faith. You’re not going to take a step on a ladder unless you believe it will support you and take you someplace worth going.

People who want to design an agnostic Buddhism for their own consumption are free to do so, but they are limiting the benefits that they would have otherwise gained from the dharma. They may find it easy here in America to sell their product as the only authentic Buddhism, largely because so few Americans have any idea about what the Buddha actually taught, but they are doing themselves, their audience, and the dharma a great disservice.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Abbot, Metta Forest Monastery

Valley Center, California

Religious institutions preserve ideas. Of course they do, that is part of their raison d’être. However, they preserve not only in script but in oral transmission, too. What could be more valuable than that? One only has to look around today at the hotchpotch of headless and rootless ideas thrown up by the New Age to value the wisdom of unbroken tradition. Even dogma is often frozen truth, halted in its development maybe but to a discerning mind capable of being revitalized.

Tradition needs working on. It will not present itself in an accessible form, especially when it surfaces in a distant culture. It takes time to reap the reward and it is churlish to think that because I can get nothing from a particular tradition, there must be something wrong with it. Religious institutions such as the one that generations of Tibetans have preserved so immaculately have been around over a thousand years and have produced some of the finest minds, some of the greatest spiritual achievers this world has ever seen, such as the Dalai Lama. To accuse this tradition of being, as Batchelor says, a “metaphor of consolation” instead of a “metaphor of confrontation” suggests that the message of the Buddha has somehow lost its cutting edge in established Buddhist traditions and is only concerned with dishing out consolation to the disempowered masses with promises of a better afterlife if they are good, is not to see the possibilities of the dynamic and living relationship that can be built up between the genuine seeker and a tradition.

Tradition needs working on. It will not present itself in an accessible form, especially when it surfaces in a distant culture. It takes time to reap the reward and it is churlish to think that because I can get nothing from a particular tradition, there must be something wrong with it. Religious institutions such as the one that generations of Tibetans have preserved so immaculately have been around over a thousand years and have produced some of the finest minds, some of the greatest spiritual achievers this world has ever seen, such as the Dalai Lama. To accuse this tradition of being, as Batchelor says, a “metaphor of consolation” instead of a “metaphor of confrontation” suggests that the message of the Buddha has somehow lost its cutting edge in established Buddhist traditions and is only concerned with dishing out consolation to the disempowered masses with promises of a better afterlife if they are good, is not to see the possibilities of the dynamic and living relationship that can be built up between the genuine seeker and a tradition.

The problem with agnostics is that they will never know. It is their nature not to know. Faith does not know either but at least it is going somewhere. Going as far as your reason will take you and no more is not to go far enough. It is true that emptiness, the ultimate nature of phenomena,  can be known by reasoning, but such an insight without faith is very rare. Nagarjuna said that faith and wisdom are the bases of practice and of the two, faith comes first. For the enquiring mind (not always concomitant with Western mind), faith is not a passive acceptance of a set of beliefs, an unquestioning allegiance to doctrine, unknowable and unprovable. Faith is a conscious decision to put trust in a doctrine having seen the benefits of doing so. It is a very active mental act and one performed not without upheaval. To have faith, especially in the doctrines of karma, the power of the Buddhas, the efficacy of the dharma, etc., is to transform one’s mental landscape, to see life very differently and to live it differently. Faith involves the putting or placing of one’s trust in something or someone. It is more giving than taking. First one sees the map, knows the road, sees the journey ahead, is sure of the incredible opportunity it offers and after much thought (and some hesitation) makes that decision to step out. It is not done lightly. I believe it is a dynamic act consciously performed by the practitioner and I do not see it as a begging bowl for morsels of consolation handed down from on high for the masses to feed on for transient succor and comfort.

can be known by reasoning, but such an insight without faith is very rare. Nagarjuna said that faith and wisdom are the bases of practice and of the two, faith comes first. For the enquiring mind (not always concomitant with Western mind), faith is not a passive acceptance of a set of beliefs, an unquestioning allegiance to doctrine, unknowable and unprovable. Faith is a conscious decision to put trust in a doctrine having seen the benefits of doing so. It is a very active mental act and one performed not without upheaval. To have faith, especially in the doctrines of karma, the power of the Buddhas, the efficacy of the dharma, etc., is to transform one’s mental landscape, to see life very differently and to live it differently. Faith involves the putting or placing of one’s trust in something or someone. It is more giving than taking. First one sees the map, knows the road, sees the journey ahead, is sure of the incredible opportunity it offers and after much thought (and some hesitation) makes that decision to step out. It is not done lightly. I believe it is a dynamic act consciously performed by the practitioner and I do not see it as a begging bowl for morsels of consolation handed down from on high for the masses to feed on for transient succor and comfort.

Batchelor talks of imagination. I’m not completely sure what he means by it but I like the word. It implies creativity and I believe that having faith is a creative act. The visualizations of bodhicitta mind training practice and of tantra are creations of worlds and realms that propel mental development. They do not require agnosticism; it would get in the way. What they do require is the tremendous creative power of the mind. Faith too is a product of this creative mind.

To refuse to accept or deny the existence of an afterlife or the law of karma is just to wait around until death comes along to prove it one way or another. I would say it is very difficult to conclusively know through reasoning, without a trace of doubt, of the existence of an afterlife. Reasons do exist, and the Indian Buddhist scholar Dharmakirti devoted a great deal of time to them in his text on logic, the Pramanavarttika. However, it is generally asserted that such things are ultimately a question of reasoned faith. They are taken on trust after a careful weighing up of all sides. Such trust grows slowly – trust in the Buddha, his words, one’s teachers, and in the tradition as a whole. One has to make choices in life; they are often made on trust. To wait until all possible facts are known would be to wait too long. As with the untraveled journey, ultimately we will put trust in those who we are sure know the way, who have been there and who we trust have our best interests at heart; while we have yet to take a single step. This is a brave decision and not some consolatory hood to pull over our eyes while we say, “Lead on Master, I cannot choose but to follow.”

Gavin Kilty

Devon, England

It’s Harder Than You Think

In the Spring 1997 issue, fellow Vipassana teacher Sylvia Boorstein describes the Third Noble Truth as the “promise that peace of mind and a contented heart are not dependent upon external circumstances.”

The Buddha makes it clear that the Third Noble Truth is the consummation of his teachings. One would be hard-pressed to find anywhere the Buddha proclaiming a peaceful state of mind as the fulfillment of the dharma. Realization of the Third Noble Truth includes Seeing the emptiness of self existence, including all states of mind Discovering the Unborn, the Deathless, as the release from the made and formed Cessation of karma (unsatisfactory influences from the past) Timeless discovery of non-dual wisdom Living of an enlightened life Liberating insights into the nature of dependent arising Joy of Nirvana.

There is a danger that dharma teachings and practices will get watered down to calmness and clarity of mind—two links of the Noble Eightfold Path, namely right awareness and right samadhi (depths of joy, peace, and equanimity).

I believe we must keep faith with the profundity of the Third Noble Truth. Otherwise the dharma in the West will suffer the same fate as Western yoga—mostly reduced to healthy exercises—only mental instead of physical ones.

We should never forget that discovering a truly liberated life is much harder than you think!

Christopher Titmuss

Cofounder, Gaia House

Devon, England

Affairs of State

As an ex-monk and a minor historian of East Asian Buddhism, I must protest the colossal misrepresentation of Buddhist tradition by Rev. Hsing Yun, the founder of the Hsi Lai temple in California, in his letter to Tricycle(Spring 1997). Rev. Hsing Yun argues that Buddhist monks do not take a vow of poverty. This flies in the face of the clear intent of the tenth training precept (injunction against monks not touching gold or silver), which is precisely to prohibit monks from personally possessing money. The Vinaya rules go into great detail about the manner in which monks shall not touch money. Perhaps Rev. Hsing Yun will do well to reread these rules.

For Rev. Hsing Yun to argue that it’s okay for monks and nuns to take part in the political process is to inject certain historical dimensions of East Asian Buddhism into contemporary American Buddhism. Buddhism in China, Japan, and Korea prospered (and as often suffered) because of its character as “State Buddhism” or “National Buddhism.” The interference of Buddhist monks in China in the affairs of state was always resented by the Taoists and the Confucians and invited terrible periodic persecutions against the sangha. Ch’an in China grew as a reaction to this norm of State Buddhism, and all reform movements in East Asian Buddhism have been attempts to get away from monastics’ involvement in State Buddhism and return to ascetic practices in the mountains.

Whatever the history of State Buddhism in East Asia may be, the political process and rules of law in America are quite different from what Rev. Hsing Yun’s understanding seems to be. Isn’t there something unseemly, if not inappropriate, about permanent residents (as Rev. Hsing Yun says the monks and nuns of Hsi Lai temple are) donating money to influence the outcome of an election in which they themselves cannot vote? There is an investigation going on at the federal level, and we shall find out how Rev. Hsing Yun’s recalcitrant stance vis-á-vis these donations squares with the laws of this country.

Those of us who are engaged in Buddhist practices of meditation as a way of transforming lives regret Rev. Hsing Yun’s version of State Buddhism. At the very least, Rev. Hsing Yun should concern himself less with legalities to defend a questionable position and devote more attention to the study of how the Buddha lived his life, and his vision of the Dharma and the Sangha.

Mu Soeng

Barre Center for Buddhist Studies

Barre, Massachusetts

Horrors of the Past

Lest we forget…the kyosaku of Auschwitz strikes again. Going with the political and humanitarian tidal wave digging and the horrors of the Holocaust indeed, why not also capitalize on it in a religious sense?

Sitting on the tracks of Birkenau, to me, borders on spiritual snobbery, and the accounts [in “Notes from Auschwitz,” Spring 1997] of the bemused states of mind testify to this. Why not sit on Tiananmen Square or the Roman Coliseum for that matter? The whole world is a battlefield!

The past is dead, the moment of action passed. What was lost in that moment cannot be brought back through a moment of clarity now. That is the nature of Suchness. The act of self-immolation of the Vietnamese monks was closer to truth.

Meditation is in the present moment, clear seeing, uncorrupted by moods, memories, or defiances. Only that holds the promise to open the path towards just and responsible action.

Maybe some people feel the need to wake the horrors of the past to make their present lives more livable. Then don’t call it a meditation retreat but rather a pseudospiritual, political crusade.

Sitting like necrophiles on the graves of the dead and drawing attention to oneself is not what Buddhism needs and moreover gives it that pessimistic slant that turns people away.

Wallowing in the past, overcome by emotions of guilt, remorse, and revenge and invoking the spirit of dead souls – what can be further from Zen?

The point is: the Buddha did not wear tinted glasses.

Wilbur May

West Palm Beach, Florida

Correction

Thank you very much for your gracious story about my retirement ceremony in your Spring 1997 issue. Allow me to rectify one mistake.

The writer states that in the course of my career, I befriended Dr. D. T. Suzuki. I did not. It was entirely the other way around. To befriend means to aid as a friend. It was Dr. Suzuki who befriended me on a number of occasions, in particular: to help me with my first Japanese visa, to help me enter Tokyo University as an auditor, and to take me in when I was ill.

Robert Aitken

Honolulu, Hawaii

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.