Go Bill!

I read Tricycle from cover to cover and don’t understand ninety percent of what I read; but the ten percent I do understand helps me “deal with life” one day at a time (hopefully with more kindness for others). Perhaps next year I’ll understand twelve percent.

Bill Krumbein

Santa Rosa, California

Food for Thought

As a vegetarian for twenty-five years, I would like to say [in response to “Meat: To Eat it or Not: A Debate on Food and Practice,” Winter 1994] that Buddhism should not be associated directly with vegetarianism. To make vegetarianism a precondition for practicing the dharma is putting the cart before the bullock.

This is not to say that I adhere to the rationalizations for meat-eating. I think that Bodhin Kjolhede is perfectly right in saying, “I suspect that the habit of eating animals is simply too pleasurable for them [Buddhists who are defenders of meat eatingl to stop.” Moreover, it seems to me that Buddhist groups should “steer” clear of involvement with non-compassionate practices,but without preaching this as part of the dharma (though it really is, on a deeper level). Practice and example do the job that preaching rarely achieves.

David Lukashok

Niteroi, Brazil

Shakyamuni’s fourfold congregation consisted of monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen. The monks and nuns of course ate whatever was served them, as long as it wasn’t an animal killed specifically for them. But laypeople, arguably ninety-nine percent of the sangha in America, are eating meat specifically killed for them as consumers when they go into a restaurant or supermarket and plunk down their cash.

V.K. Leary

San Francisco, California

I was surprised to find no reference in the food debate to the yet wider implications [of meat eating]—that consuming grain-fed animals has a huge effect on the world’s hungry and our own and growing agricultural difficulties; how our food choices lend weight to the multinational agricultural forces now in control; how this is interdependent and connected to world hunger where half of the U.S. harvested acreage goes to feed livestock. Where, in Third World countries, those in need of that grain itself are too poor to buy their only accessible protein source. How the poor, growing hungrier, are compounded by the nature of the market as exported and livestock food production takes up land that once grew beans and grain for human consumption. Don’t all other lesser questions fade upon knowing this?

Jean M. Hoelzle

Metamora, Michigan

To be aware of the craving, to be aware of the guilt, to be aware of the denial, and above all to be aware of the suffering I support to satisfy craving—this is the kind of practice I would expect to see described and encouraged in a Buddhist publication. But now, thanks to Tricycle, I’m comforted to know that restricting my diet to vegetable products may be an unhealthy practice and would likely mean that I’m self-righteous or attached to vegetarianism.

Dewain Belgard

New Orleans, Louisiana

Since my book Famous Vegetarians and Their Favorite Recipes has a picture of Shakyamuni Buddha on the cover, I assume that it is to my book that Helen Tworkov is referring in “Editor’s View” (Winter 1994) when she writes: “A book of ‘famous vegetarians’ features an image of Shakyamuni Buddha on the cover, but it makes no mention of Adolf Hitler despite his well-documented vegetarian eating habits.” Although Ms. Tworkov (and Ms. Wheeler as well) seems to regard Hitler’s vegetarianism as an irrefutable fact, the truth is that there is compelling evidence to suggest that he was not a vegetarian. The most damning piece of evidence comes from the woman chef who used to prepare Hitler’s meals at a hotel restaurant in Hamburg in the late 1930s. On page 89 of her Gourmet Cooking School Cookbook (1962), Dione Lucas wrote: “I do not mean to spoil your appetite for stuffed squab, but you might be interested to know that it was a great favorite with Mr. Hitler, who dined at the hotel often. Let us not hold that against a fine recipe, though.” Robert Payne in his Life and Death of Adolf Hitler, attests to the Führer’s fondness for Bavarian hams and sausages. J. H. Toland in his biography of Hitler mentions his liking for meat patties and roast pork. Albert Speer, Hitler’s protege and confidant, in his memoirs mentions Hitler’s predilection for ham, liver, and game. At the time of his death, Hitler’s bunker was equipped with a well-stocked meat-locker. It is true that his doctors put him on a vegetarian diet for brief periods to cure his excessive sweatiness and flatulence, but he was constantly backsliding.

Rynn Berry

Brooklyn, New York

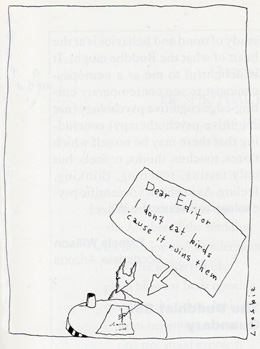

While we appreciate being corrected about Hitler, the inclusion of Shakyamuni Buddha in a book about vegetarians contradicts the historical record.

–The Editors

A common thread of the discussion on vegetarianism in the Winter 1994 issue is the applicability of a sutra describing the practices of the bhikkhus. The Buddha permitted the bhikkhus of his time to accept an offer to share a family’s food, as long as no animals were killed expressly for that purpose. The question in that agrarian society was the proper attitude to take toward an honest gesture of hospitality.

We face a different question. Every time we make a purchase from a fast-food outlet or supermarket, we provide consumer information which will be used by farms, ranches, and slaughterhouses. We must share responsibility if animals are killed because of choices we make.

Marc Bedner

Bloomington Springs, Tennessee

I’d like to express my appreciation for your inclusion of John McClellan’s essay in the debate on food and practice. Unlike so many others who have presented the familiar good and rational reasons for practicing vegetarianism, McClellan speaks with the voice of a poet, revealing the depth, the sadness, and the compassion involved in cultivating this perception of profound paradox at the very bone of our existence. His thought- provoking article “Non-Dual Ecology” (Winter 1993) was one of the most remarkable and arguably most deeply Buddhist pieces you have ever printed; I look forward to more of his challenging essays in future issues.

C. W. Haney

e-mail

House of Mirrors

The article “Finnegan at His Wake” [Vol. IV, No. 2] is essentially the first chapter of Stephen Butterfield’s new book,Double Mirror: A Skeptical Journey into Buddhist Tantra, While the book as a whole is a powerful invitation to (skeptically) explore the tantric path as presented by Chogyam Trungpa, someone who reads only this excerpt and not the book might well be turned away from Buddhism in general, or tantric Buddhism, or the specific teaching of Chogyam Trungpa, and would likely be quite surprised to learn that Butterfield’s dedication reads “Homage and grateful acknowledgment to all my teachers from the ten directions and the three times—without whom neither this book nor the dharma could exist.”

Newcomb Greenleaf

Yonkers, New York

Please cancel my subscription to your magazine. I am a student of the Venerable Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and even though he is gone he continues to inspire me a great deal. If accurate information cannot be obtained about our Guru it is not necessary for me to read anything about him.

Arsenio Sierra

Hopewell, New Jersey

There is no doubt in my mind that Trungpa Rinpoche was a Buddhist meditation master of exceptional skill and a highly realized teacher. Trungpa showed us that the awakened state or primordial mind is inherent in our own makeup. He gave us the “pointing out” instruction to awaken our recognition of this, our fundamental nature and human birthright. And he also gave us instruction in the correct practice of the path of meditation in order to further our direct experience of our innate wakefulness.

Contrary to Mr. Butterfield’s portrayal of our “revered tradition,” our lineage has always been controversial. The life stories of the early mahasiddhas, our spiritual forebears, reveal that they led very unconventional lives. Just as we do not doubt the value of their spiritual attainment, neither should we let the non-conventional behavior of Trungpa Rinpoche and the controversy of the last several years in any way make us doubt the value of the teachings which he gave us or our own direct experience of the awakened state of mind which is the result of his presence in our lives.

I came away from Mr. Butterfield’s article with the uncomfortable feeling that much of his criticism of Trungpa and his lineage stemmed from a misinterpretation of some of the fundamental Buddhist teachings. For instance, he seems to assert that our meditation practice is intended to repress our thoughts and emotions. As Kalu Rinpoche points out, the true nature of mind is “empty but luminous.” The practice of meditation is meant to validate this understanding of the nature of mind through one’s own direct experience. Our path as Buddhists is to apply ourselves to the practice of meditation, to work with body, speech, and mind in such a way as to further, through the awakening of prajna, a direct experience of the ultimate nature of mind. This is the experience of sunyata, of emptiness or twofold egolessness. This is what Trungpa Rinpoche, as my “Vajra Master,” pointed out to me and to everyone who met him.

We have been told that the ultimate nature of mind is a very simple truth. It is simple in the sense that it is ordinary and innate. It doesn’t exist somewhere outside of our own experience but is inherent in our own situation. This doesn’t mean that the path to realization is easy. It takes tremendous effort and discipline. That we can acutely break through our resistance and sit and practice meditation is proof that prajna—or egolessness awareness—exists.

According to the teachings of Mahayana we cannot ascribe a “who” or “what” to that awareness which seems to stand outside of the thought or emotion. There is only tathata— thatness. In the awakened state of mind there is no room for the habitual creation of a self as a reference point. The belief in a self as a solid entity, a reference point which uses experience to confirm its existence, is a fundamental misconception of the ultimate nature of mind. The belief in an experiencer as separate from the experience presupposes a duality which does not ultimately exist, and this habitual misconception of the ultimate nature of reality only leads to continued suffering— to further rebirth in the six realms of existence.

By insisting on being an “uncooked carrot,” on experiencing and celebrating his own funeral, Mr. Butterfield seems to not understand this essential point. This incorrect view taints the whole article. Certainly the last few years have been exceptionally painful ones for our community, and I sympathize with Mr. Butterfield’s doubts and questions. I have been forced as well to look at my own connection to this lineage and the Buddhist teachings in general. Yet I cannot forget the presence of my teacher which so clearly manifests the profound wisdom and compassion of our lineage. The events and controversy surrounding our recent history make it painfully clear to me just how fragile and precious the opportunity for hearing the Buddha dharma is in this world.

To reject the “Vajra Master” and to forget the brilliant manifestation of awakened mind which his presence brought into our lives is to forget our own Buddha-nature. This is worse than never having met with the dharma in the first place. It is not without serious consequences karmically. So please be careful, Mr. Butterfield.

Tashi Armstrong

Brunswick, Maine

Dear Stephen Butterfield,

I am not a Vajrayana student so I cannot vouch for the statement “accept the path as given or fry in hell,” nor have I heard that the sibling rivalry of Karmapa’s sons led to the bumping off of Jamgon Kongtrul.

I am a devoted student of Chogyam Trungpa and have been a Mahayana practitioner for twenty-five years. I am sorry that you got burned and I admire your account of your experience written with candid, fearless expression.

One can only speak for oneself on the effect of Buddhist training and you speak with clarity as you examine your journey. Seems to me you have progressed on the path.

Good luck, and as Chogyam Trungpa so often said, “Have a good time.”

David Stinson

Antigonish, Nova Scotia

It seems to me that every great teacher had their detractors. Christ had his Judas, Buddha had his faithless monks, and so on. But a great teacher is not judged by those who failed to properly connect with his teachings. A teacher is judged by his or her accomplished students, and by the resultant degree of generational carryover. A student’s success is dependent upon the joy and sincerity of their hard work and devotion. I am a twenty-three-year-old, second-generation Buddhist. My parents were followers of the Venerable Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and are extremely devoted practitioners. I am exceedingly proud of my upbringing. As a child I attended the Vidya School, which was founded for the children of Rinpoche’s students. We were made to meditate, wear uniforms, and adhere to rigorous academic standards. In recent years I graduated from the University of Buffalo with high honors and a near perfect academic record. My sangha peers have gone on to perform well at some of the most respected universities in North America. Those who have not chosen academic tracks are leading relatively normal lives: working for environmental causes in Washington, D.C., backstage at the Santa Fe Opera, or as TV and movie actresses, and so on. To my knowledge there are few of us who suffer serious drug or alcohol problems and many who are involved with stable monogamous sexual relationships. If Trungpa Rinpoche was such an irresponsible, alcoholic, brainwashing, sexual abuser of our mothers, then why are we, their children, leading such healthy and productive lives? If something was dubious or lacking in the environment of our upbringing, then how can our collective success and continued devotion to this teacher be explained?

Noah Richman

Barnet, Vermont

I was very pleased to read Stephen Butterfield’s article. The political issues that exist in all communities, whether religious or secular, should not be ignored. I have seen too much of the same unquestioning attitude toward dharma organizations here in Europe. The dharma is really not about faith, but rather about doubt. It is not that we should distrust the dharma, but rather that we should investigate whether we have understood it right or maybe got something wrong. It is not that we should distrust the master of the dharma, but rather that we should check him or her out before committing ourselves to their guidance. If we come to distrust his or her person, we should cherish the insights and advice he or she has given us. The true lama is the lama within us. My teacher, the very venerable Lama Gendun Rinpoche in France, has taught us that the very first characteristic of the bodhisattva is that he or she makes many mistakes. This, I suppose, is a natural consequence of being open to others. The second characteristic, though, is his or her ability to purify these same mistakes. Faith or trust in the dharma and/or the lama comes naturally when all doubts have been removed. This is the teaching of the Buddha himself. As modern Westerners, we should not fool ourselves about hidden doubts. They are there. When all doubt has been removed, it is called certainty. There is a process that has to be allowed to take its course. Questions keep the mind open and curious; answers close it down and move our attention away from unresolved issues.

Gelong Tendar

Denmark

One and a half cheers for Stephen Butterfield’s article (Winter 1994), a courageous attempt to find his individual voice in the face of authoritarian manipulation and appalling ethical contradictions. But why does he not question his own conditioning more closely? Is he so sure that the organization to which he belonged ever reflected the original traditions of Buddhist tantra? Throughout the article he refers to “Vajrayana” when he is actually describing phenomena, attitudes, and ethics unique to that one organization. To assume that this group, with its sad aberrations, is equivalent to the whole Vajrayana tradition is wholly incorrect and fundamentally misleading to other practitioners of the Buddha dharma.

Y. Gyaltsen

Oxford, England

I too am a student of Trungpa Rinpoche who has at times felt many of the same feelings as Stephen Butterfield about the Teacher and the teachings, but something Trungpa Rinpoche said to me during my time at Samye Ling [in Scotland] has always echoed in my head.

I had just come from working in the garden and heard my name called. I looked to the balcony and saw Trungpa Rinpoche sitting on the floor near the bathroom. He waved to me and said he needed my help getting back to his room. As I approached him I could detect the odor of alcohol in the air. I, of course, had heard all the rumors of drinking, drugs, and sex, but had never seen anything myself so I was trying to be fair, though it did taint my mind. I helped him up and back to his room, and as we entered he said, “I understand you have been having trouble meditating. Sit here,” he said, gesturing toward some pillows at his side, “and meditate for me.” What ran through my mind was something like, “What can this drunken person do for my meditation?” Suffice it to say, after a bit I could feel him in my head cutting this bind, untying this knot, and releasing this staple until the top of my head floated free and I had 360-degree vision!

As I was turning the doorknob and bowing to him he said, “Always separate the man from the teacher.” This has stood me in good stead and I will always carry it with me.

Bob Gottlieb

Tucson, Arizona

Baker’s Dozen

There are a dozen rationalizations to justify why the self-appointed karma squad has tried to ostracize Richard Baker Roshi from Buddhist events or conferences in North America following his 1983 fall from favor with the San Francisco Zen Center. Sadly, these attempts have reflected aspects of the so-called “Buddhist Community” that are themselves problematic: moral righteousness, punitive impulses, finger-pointing, and dogmatic personal opinion. Congratulations toTricycle for once again going against the grain and allowing this engaging man to speak for himself rather than allowing his reputation to remain controlled by the dharma spinmeisters.

Chris Meltzer

Toronto, Ontario

I enjoyed your interview with Richard Baker Roshi (Vol. IV, No. 2). As a psychotherapist and Zen student, I tend to agree with his view of psychology and Buddhism as separate and complimentary The further point that he doesn’t pursue in the context of this exchange is where the two approachesoverlap even when we’re not trying to integrate them. Baker Roshi points out two essential areas of overlap without naming them as such. One is the psychology of the teacher-student relationship, with its inevitable projections. The more general issues of “transference” and “counter-transference” lie behind this psychology. Psychoanalysts from Freud on have studied these issues in depth and have something to contribute to our sensitivity in this realm.

The other area concerns what we ask or otherwise use as a focus to embed ourselves in present Mind. Baker Roshi suggests one of countless possible questions to oneself: “Why do I relate to my spouse in a certain way?” Self-inquiry with this kind of personal and interpersonal tinge arises at the interface between psychology and Buddhism. In their own ways, both fields nourish such a question, reverberate with it, grow from it. It’s potentially confusing territory, since the questioner may wonder in which direction lies more fruitful exploration. A psychological direction would emphasize content and tap into transference issues again. A spiritual direction would use the question in some sense as an incidental probe. Pursuing the two together is possible but a little tricky in that it lacks the cleaner simplicity of a single-minded method.

In contrast, opening to present Mind through impersonal phrases or questions falls more clearly within the boundaries of spiritual practice. Baker Roshi goes on to cite a few reminders of this kind: “Arriving in the present,” “Already arrived!,” “There’s no place to go, and there’s nothing to do.”

Tony Stern, M.D.

Hastings-on-Hudson, New York

Baker Roshi expresses an error which I think it is worth clarifying. He stated that Buddhism is not psychology—but in fact, he misspoke the issue out of a common misconception. Buddhism is not psychotherapy, it is not clinical psychology—there he is correct. According to historians such as David Kalupahana, the Buddha was the first psychologist, for the science of psychology is the study of human mental processes and behavior, their conditioning, motivation, and interaction with reality. Buddhism is, of course, more than a science, but the study of mind and behavior is at the heart of what the Buddha taught. It is delightful to me as a neuropsychologist to see contemporary cutting-edge cognitive psychology (not cognitive psychotherapy) concluding that there may be no self which tastes, touches, thinks, or feels, but only tasting, touching, thinking, feeling. As in physics, scientific psychology reinvents the Wheel.

Pamela Willson

Scottsdale, Arizona

The Buddhist Sex Quandary

I read with interest the letters in the Winter 1994 issue disapproving of your publication of articles dealing with issues of sex and sexuality. Intentionally or not, that issue also contained an article by Sallie Tisdale that is certain to provoke similar complaints.

Perhaps the “offensiveness” lies not in the articles you have published, but, instead, in the personal presentiments, opinions, and judgments that those who are offended bring with them when they consider such traditionally “delicate” issues as sex and sexuality. The focus and content of a publication like Tricycle should attempt to be as broad, as deep, and as inclusive as the Buddha dharma of which it is but a reflection. Please continue on the editorial path you have chosen.

Michael F. Natola

Carlisle, Massachusetts

I was very pleased to open Tricycle and find Sallie Tisdale writing about sex and Buddhism. What she has to say was personally extraordinarily valuable to me by challenging my honesty compassion, and the limits imposed by self and culture. She is a woman of courage, forthright-ness, and intelligence, sometimes dangerous and often painful qualities to have and live in our society. My thanks to her, and hope that she persists.

Nancy Little

La Jara, New Mexico

I very much enjoyed your Winter 1994 issue, and in particular Sallie Tisdale’s “Nothing Special: The Buddhist Sex Quandary,” in which she muses on Buddhism’s seeming indifference to matters sexual. I would have thought that her desire, vis-a-vis sexuality, to be “sincerely accepting of the enormous variations in human behavior” was shared by all Buddhists. However, recently, letters to the editor in this and other Buddhist periodicals demonstrate otherwise. And so it is all the more courageous of Ms. Tisdale to use the Tricycle forum to “come out” at the national level. She says that she is “most comfortable calling myself. . . bisexual,” as this “feels most wholehearted and correct, as labels go.” She suggests that “in this divided world, we have to call ourselves something sometimes.” This is most unfortunate. Ironically, when I read Ms. Tisdale’s essay, I had just studied an exegesis of the Heart Sutra by the Korean Zen master Mu Soeng Sunim. In it, the author observes that “all categories are ultimately dualistic.” The only-too-human tendency to categorize, he writes, robs us of the “wisdom essential for enlightenment.” Labels turn us into objects, reinforcing the subject-object duality. I think the point is simply this: Bisexuality should be regarded as something we do, not what we are.

James Martin

Corpus Christi, Texas

Tricycle Knut

Several letters to the editor in the Winter 1994 issue reflect minds that take refuge in labels and self-righteousness rather than strive for understanding and compassion. Concerns with something as banal as “taste”; suspecting Tricycle of becoming the voice of “the ‘Buddhist Left,’ or the Mother Jones of American Buddhism”; labeling the feature on Miranda Shaw as “pornography”; and describing Tricycles acknowledgment of sex as an “incomprehensible preoccupation”— represent such whining partisanship and superficiality as one would hope a Buddhist to have overcome.

My initial reaction to the articles about John Giorno and Issan Dorsey also was, “enough is enough, give me holy men, not drug-addicted homosexual sluts.” However, my complaining and whining letter to the editor never made it out the door; it did not seem very constructive, after all. Self-awareness and the overcoming of the limitations of self require existential journeys that cannot be confined to antiseptic academic ivory towers, or middle-class suburban aesthetics and sensibilities. Since when is Buddhism about idol worship, role models, and political correctness?

Interviews such as the one with Beastie Boy Adam Yauch and articles such as Stephen Butterfield’s grapple with Buddhism on a personal, reality-oriented, nonsectarian, and nonacademic level that has vitality, meaning, and relevance. Keep it up!

Knut W. Barde

Strathmore, California

Pandering to Purism

I felt that a vital concept of Buddhism was neglected throughout the entire dialogue on Dharma, Diversity, and Race(Fall 1994). Is the dharma not foremost a matter of faith and practice, or instead does it pander to matters of ideology, culture, and phenomenological purism? Throughout its history, Buddhist practice has developed into many rich and diverse traditions, some of which were the result of heated philosophical dispute. In addition, I dare say that all major schools of thought as they exist today scarcely represent the exact Shakyamuni ontology. Therefore, I did not figure that xenophobia would become so readily confused with cultural difference in Tricycle until now. If I must buy into a view that cultural baggage is necessary in order for one to benefit from Buddhism, then I would say that your Gnostic version of the dharma is weak indeed. While at times I found Victor Sogen Hori’s commentary very good at describing the stereotypical “white” psychology brought into every American sangha, I would similarly argue that a Japanese Zen roshi would report finding similar drastic differences between himself and a Korean practitioner. For instance, after readingThe Three Pillars of Zen, a Korean Zen monk wrote that Philip Kapleau knows nothing about tradition. After his voyage to China, Dogen wrote that no one in all of Japan knows the Way. This of course merely reflects how difficult enlightenment is for all of us to understand: white, black, or Asian. All these unique personal agendas we bring into a sesshin have one thing in common: It is called Samsara, and the last time I checked, white people did not own any exclusive rights to it whatsoever!

Robert Schaefer

Dayton, Ohio

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.