Conflicts of Interest

Every time I turn to your letters page I find another batch of readers canceling their subscriptions, citing some outrage to their sensibilities like gay tantra or Richard Gere. Do you realize that if this trend continues, you are going to be left with a readership comprising just a load of open-minded, non-judgmental types who actually welcome having their preconceptions challenged? You have been warned!

David Lewis

London, England

The Fifth Anniversary Special [Fall 1996] entitled “Psychedelics: Help or Hindrance?” was most welcome indeed, for in an adult, serious, balanced, and dignified mode it presented information that is usually distorted, paranoid, self-serving, politicized, and seriously misleading.

If the ears of all the people in this nation who had ingested illicit substances in the past six months turned bright green for one whole week, the nation would be shocked, astounded, amazed, confused, flabbergasted and quickly taught something very important as they identified local friends, relatives, neighbors, judges, doctors, lawyers, accountants, priests, nuns, ministers, rabbis, soldiers, police, firemen, businessmen, teachers, students, politicians, as well as respected policy makers, administrators, supervisors and workers. They would immediately come to understand that there are such things as pleasurable and responsible drug use as well as damaging and irresponsible drug abuse.

It is shameful that our approach to drug use and drug abuse remains so puerile, ignorant, and vindictive. We need truthful information about responsible drug use and irresponsible drug abuse, of both licit and illicit drugs. We need to change from a repressive and demonizing response (using police, prosecution, and prison) to a reasoned and compassionate response (using education, treatment, and rehabilitation), by demonstrating that existing policies are counterproductive, only exacerbate a horrible situation, waste public moneys, and are in need of drastic change. We seem unable to learn from the painful history of alcohol prohibition.

Tricycle brings light where there is darkness, hope where there is frustration, and compassion where there is hate. I am heartened by your courage and perspicuity.

A. C. Germann

e-mail

Equanimity is easy when reading about art or mudras. But write about drugs and watch how we all haul up Our Positions. I was afraid someone brilliant in your magazine might change my mind, but no. As Robert Aitken said, “When I hear this talk I feel transported back about thirty years . . . like kicking a dead horse.” As we used to say before we grew up, this issue was a trip.

Morgan Ames

Beverly Hills, California

I am a physician and have prescribed various drugs that alter mood, consciousness, and personality, and have some years of research into therapeutic psychoactive medicines.

The discussion of whether psychedelic drugs produce states identical to those achieved after Buddhist practices, or whether these drugs aid Buddhist practice was interesting but seems empty. Perhaps the use of such drugs could improve the quality of interpersonal interactions and have some social function, but these drugs seem irrelevant to what the Buddha experienced and offered. He even warned against mind-altering substances.

J. J. Martindale, MD

Boulder, Colorado

My two teenage sons took one look at the Fall 1996 cover and (separately) declared: “Drugs don’t fit with Buddhist dharma! Why do you subscribe to this trash?”

Now we have talked about how, editorially, you offered a very balanced presentation with regard to psychedelics and American Buddhism.

Undoubtedly psychedelics can open one to the possibility of enlightenment. Yet on my personal journey I have found that at times I try to bring on sensations that reassure me that I am making progress on the path. Does the use of psychedelics feed this kind of need? Are not the need for (immediate) gratification and the pursuit of desired feelings cultural impediments we must face if we are to deepen our practice? These are some queries I would offer as we reflect on psychedelics and the dharma in America.

Becky Van Ness

Waite Park, Minnesota

I would like to express disappointment with the discussion of the question of psychedelics. Rather than addressing the question, the magazine came across as an advertisement for drug use. Buddhists who take the fifth precept literally were not only in the minority, they were hardly mentioned. While I am aware that many Americans came to Eastern philosophy via drug experiences, I do not think you gave sufficient voice to those practitioners who do not accept any drug-taking, let alone that masked by a spiritual context. I hope that in the future you will attempt to better balance your presentation of the issues you raise.

Michelle Johnson

Gainesville, Florida

For two years, I’ve been meaning to write to Tricycle to suggest an issue on Buddhism and psychedelics. Now I suppose I must give some credence to the powers of telepathy. In any case, the issue (in both meanings of the word) proved even more fascinating than I’d imagined it. Thanks!

It’s interesting that the strongest opposition to psychedelics came from those Buddhists with a vested interest, emotional and/or financial, in orthodox methodology. I’m left wondering if they are not as stuck, and do not miss The Point as widely, as persons with vested interests in capitalism, communism and all the other ravenous “isms” that gnaw at liberty’s bones?

Tom Robbins

Laconner, Washington

To introduce any intoxicant as a “sacrament” is disrespectful of the dharma itself. What worked at a Grateful Dead concert should not pervert one’s practice.

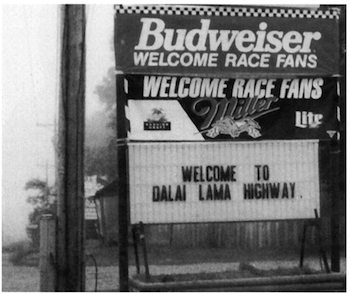

Teachers such as Thich Nhat Hanh and the Dalai Lama have addressed the present generation as being responsible for what will ultimately become known as “American Buddhism” to future generations, which may include our own children. And it is sad to think we have confused the “don’t worry, be happy” attitude with “everybody must get stoned.”

Mike Costanzo

Columbia, Tennessee

As Aitken Roshi wisely points out, just because certain cultural circumstances of the time (or perhaps more accurately, certain karmic circumstances) happened to bring many people to Buddhism does not in and of itself mean that drug use is beneficial or helpful to spiritual practice. The virtue (if one can call it virtue) of psychedelic drugs was that it enabled many people to see that reality was not what it appeared to be. That there was more to the supposedly objective world than our dualistic consciousness let on. It was this revelation that ultimately brought so many of us to Buddhism. But the notion that taking drugs somehow accelerates our progress towards enlightenment is absurd. In fact, the opposite is true. The psychedelic drug experience is one of hallucination—a makyo. After all, makyo are merely temporary unreal states that serious practitioners may experience during intensive zazen or meditation. My teachers have always and repeatedly pointed out that makyo are not something to cling to, nor are they to be sought out as a desirable experience, but rather one must recognize the makyo for what it is, and then return to the practice. Furthermore, it must be said that any “experience,” however exalted or sublime, falls short of true enlightenment. As my teacher, Roshi Kapleau, has said, enlightenment is not an experience that stands against other experiences, rather, it is that which underlies all other relative experience. Strictly speaking, as long as we experience even “enlightenment,” it is, necessarily, not true enlightenment. That is why in Zen so much emphasis is placed on getting rid of any trace of self-aware enlightenment, which only hinders the selfless functioning of our true compassionate mind.

Peter Greulich

Wakefield, Massachusetts

I found your issue on Buddhism and psychedelics to be highly relevant. Despite your impressive list of contributors, however, and your obvious attempt to cover all bases, the question as to what, if any, benefits psychedelics might have to offer seemed to have been left to resolve itself in an all-too-familiarly ambiguous manner. I am concerned that this conditional status may therefore be too easily overshadowed by the more authoritative and negative views that were expressed by Robert Aitken Roshi and Richard Baker Roshi. For who are we to argue with a Zen master?

Unfortunately, though their descriptions of the potential dangers and impediments that psychedelics might pose for a Buddhist meditator may be real, the paucity of their own personal experiences of the psychedelic sort have led them to represent such states and their value in a rather naive and elementary manner. Though the question as to whether psychedelics are “good” for one’s personal spiritual development is important should not confuse this question with a more objective appreciation and assessment of the profoundly creative, internally-lit dimensions that psychedelics provide access to.

The fact is that there is an entire spectrum of mostly uncharted psychedelic experiences and states that are qualitatively different from those described by Buddhist and other meditators. In addition, it should be a matter of no little interest that there is a class of chemicals that are able to instantly elicit temporary experiences of insight and understanding comparable to those that are otherwise achievable only after spending twenty-five years in a cave. That psychedelic enlightenments rapidly fade does not thereby erase their significance. In fact, they raise an entire gamut of profound and potentially answerable questions about the nature of consciousness, enlightenment, and chemistry that, to my mind, cry out to be explored.

A disparaging orthodox Buddhist perspective that treats psychedelic states as no more than super-samsara and therefore to be avoided, misses their potential value entirely. Being a good Buddhist should not mean to cease from exploring the frontiers of our interests and minds just because we are not yet enlightened. Psychedelics provide a uniquely powerful experiential vehicle for accessing unknown and autonomous aspects of the human psyche that may be of great scientific, psychological and spiritual interest. As Ram Dass, Terence McKenna, and Nina Wise each mentioned, meditational experience could be most helpful in navigating such internal terrain.

The human pursuit of altered states has traditionally been linked to healing and growth. It is only in our present Western culture that uneducated use has led to a negative stigma. It would be unfortunate indeed if American Buddhism is allowed to become overly puritanical, especially since so much initial interest in Buddhism is owed to the psychedelic experience. A more helpful attitude would be to participate in creating a healthy and supportive “setting” in which altered states could be taken seriously and actively explored.

Earl Davis

Leonia, New Jersey

Thank you for your illuminating Fifth Anniversary Issue. Before I read it I wasn’t sure how I felt about psychedelic drugs. Now I’m sure I don’t know.

Stuart Cadenhead

New York, New York

I am disturbed that your last issue presented few, if any, of the negative and damaging potentials of psychedelics. Some practitioners may be open and wise enough to benefit from a psychedelic experience; however, some are not—particularly those who are psychologically cut off from their hearts and bodies. Your last issue failed to take the full range of practitioners into account. I feel this was irresponsible.

Buddhist practice teaches us to work with whatever arises, including changes of consciousness and the emotions that can arise through those changes. However, the reality is that some people are not ready to work with the depth of change that psychedelics can rapidly usher into their lives. In my opinion it is unwise to take psychedelics—or even push forth into deeper meditative states—before one has found a resting place in his or her heart and body. The risk is of having the rug of “consensual reality” pulled out from beneath oneself before the essential resources of an open heart and grounded body are present to draw upon for stability. Fears and doubts can arise that the person does not have the inner space to work with. What can result is an upsurge of hindrances that do not get worked with—only creating unnecessary turmoil and psychological distress. The person may close down and be reluctant to keep moving on the path.

It may seem like common sense that psychedelics should be avoided by people not grounded in their hearts and bodies. However, this wisdom is not always so obvious to newcomers to psychedelics. Particularly when cautions are often reduced to such insufficient explanations as “You must be somebody, before you can be nobody.” Psychedelic drugs have received a lot of good “spiritual press.” The intense experiences described by many users create an exotic aura of rapid spiritual progress—often feeding readers’ fantasies about what enlightenment will do for them. Granted, this interest can be useful on the path and, granted, it’s “good for business,” but some people will be enticed into trying psychedelics who are not prepared. I feel we have a responsibility to those people.

Greg Sarafian

Davis, California

I want to thank you for such a balanced and comprehensive look into psychedelics. Although I have never used them myself, I have known many who have. There was so much to learn from your many articles. I enjoyed my copy very much, as always.

Joyce Johnson

Sylvania, Ohio

Count me in the Ram Dass/Alan Watts camp. I have a sort of “generational” spin to my opinion. I’m twenty-eight, grew up in a “charismatic” Christian household, and attended a private school populated primarily by practicing (if not “religious”) Jewish people. I notice that for many people my age, “spiritual” seeking or practice of any kind did not have a prominent place in family life. For many of those people, drugs themselves and/or a community of drug takers provided the first fleeting confirmation that a spiritual or existential dimension exists at all. Whereas I sense that many “seekers” twenty or thirty years older than I am were presented with a rigid, dogmatic brand of religion, I gather that some of my age cohorts were left with a complete void. Personally, I can’t dismiss my belief that certain drugs played an indispensable role in some people’s spiritual development—“indispensable” only because that role was neglected by parents and social institutions.

Barbara Saunders

Oakland, California

e-mail

Your issue on Buddhism and Psychedelics was extraordinary, indeed historic. Well done!

I believe that there is a consensus: Psychedelics open the doors of perception; meditation allows passage.

For instance, meditation (sitting forms) under the influence of cannabis is an interesting synergy mentioned by Alan Watts. I have long found this combination a highly potent tool for gaining rich philosophical and psychological insights – itself a most worthy endeavor. But even in such a union psychedelics probably will not lead to religious attainments. For me, hours or days of zazen usually followed by vigorous walking meditation, i.e., mindful hiking, has been the most efficacious. Cannabis is inappropriate for the zendo, but it does have its proper place and situation in Buddhism.

Debra Jan Bibel, Ph.D.

San Francisco, California

I love it! “The Breakdown Ball” [“On Gardening,” Fall 1996]. Finally something I can relate to in this Buddhism and Psychedelics issue.

B. C. McCann

Winchester, Indiana

Agreeing or disagreeing neither validates nor invalidates most issues. If I canceled a magazine subscription every time I disagreed with an included article, I would have no magazines in my life.

I look forward to placing my eyes on the pages of your next issue, and my ear to the ground in anticipation of the long howl that will inevitably follow your special issue on “Buddhism and Psychedelics.” I also look forward to enjoying a long-term subscription to Tricycle.

Joseph P. Reel, Ph.D., LPCC

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.