When The Three Pillars of Zen appeared in 1965, it had a monumental impact on the direction of Buddhism in North America. Compiled by Zen teacher Philip Kapleau, it combined a series of talks for beginning students by Yasutani Roshi with classic Zen texts. Most important, it offered the first how-to instructions for Western practitioners; after a decade of widespread interest in Zen—generated by the books of D. T. Suzuki and Alan Watts—no longer could an American read about Zen and not know where to begin.

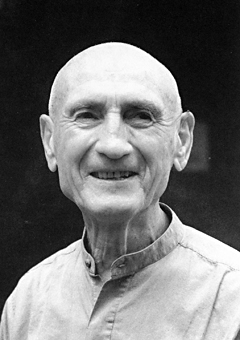

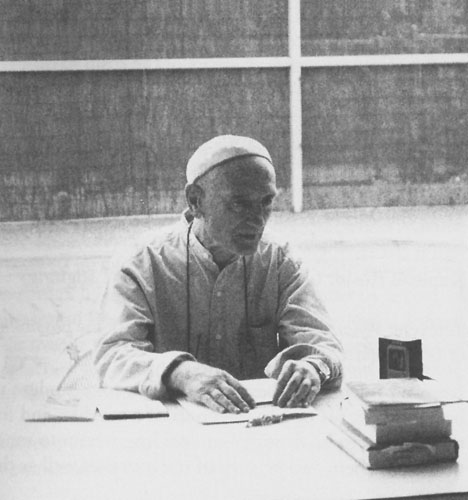

Kapleau Roshi was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on August 20, 1912. During the Depression, he went to night school to study law with money earned as a court reporter, but had to quit for health reasons. His reporting skills led to his military assignment, in 1946, to cover the Nuremberg war trials. From Germany he applied for a transfer to Tokyo, where the war trials were just beginning. There, Kapleau was struck by the difference between how the Germans and Japanese were handling their defeat and became determined to understand the laws of karmic retribution by which the Japanese accepted the ravages of war as payment for the harm they had initiated.

From 1953 to 1965, Kapleau trained in Japan, primarily with Harada Roshi, Yasutani Roshi, and Soen Roshi, three of the most respected Zen adepts of this century. On returning to the United States, he founded the Zen Center in Rochester, New York.

A few years ago, Kapleau Roshi developed a mild case of Parkinson’s disease. Today he lives in Hollywood, Florida, where he continues to lead workshops and work with individual students. The Center in Rochester continues to thrive under the leadership of his successor, Bodhin Kjolhede.

In 1990, Doubleday published a twenty-fifth anniversary edition of The Three Pillars of Zen. To date, it has been translated into twelve languages and has sold almost a million copies. It remains one of the most influential and inspiring Zen books in the West.

This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Helen Tworkov at Kapleau Roshi’s residence in Hollywood, Florida in March, 1993.

When Zen Master Soyen Shaku came to the U.S. in 1893 to attend the World Parliament of Religions, he was very optimistic about Zen in the West—as were many of your own teachers, such as Yasutani Roshi and Soen Roshi. On many occasions these teachers expressed disgust with the Japanese Zen establishment and looked to the West with tremendous hope. Do you think we’ve merited their optimism? I would say so. Many of the teachers in Japan were hopeful about America because of our great ability to get things done here—in terms of starting a monastery or center. What will happen from now on is anyone’s guess, because things are always changing. We’ve had our ups and downs, but on balance I think we’re still moving ahead. Among scholars and educated people, Zen is still highly respected. But I feel that we teachers have not been able to make known to the mass of people the great benefits of Buddhism. We’ve touched the minds of the educated people, certainly. But we have not yet touched their hearts. As a new religion comes to a country, it faces not only opposition from the established religions but the problem of adapting itself to the culture without sacrificing the qualities that make it unique and desirable. It’s not easy to take a tradition that is so totally foreign to most Americans and adapt it without throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

As the teachings take root here and become “Americanized,” are the differences between American values and Zen cutting deeper or getting closer? The essential or fundamental elements of Zen are not, we discover, so foreign to us. But in the acculturation process one of the strongest obstacles is the absence of the notion of a God in Buddhism. There’s no doubt that the “God problem” is a bone stuck in the throat of a great many people. There is room for all kinds of interpretation. And ways for people to manipulate—and I use the word purposely—Zen, to favor a particular point of view. The ordinary person finds it very hard to conceive of a religious teaching that has no God.

How do you feel about how Zen is now being interpreted by American practitioners? While you, for example, have maintained a focus on enlightenment, we see an increasing tendency to interpret “everyday Zen,” or daily-life Zen, in ways that have more to do with lifestyle than with enlightened view. Basically, we live in a self-indulgent society. But actually I have let up on talking about enlightenment so much. My own experience of almost thirty years teaches me that there are very few people who have the kind of do-or-die aspiration necessary to achieve awakening. I don’t think that is entirely tied to our insistence on comfort. Americans have, even in modern times, done some pretty heroic things and have undergone suffering for the sake of others. So, that kind of determination is there. But I think the preparation for the arousal of it—the training—has not been fully developed.

Recently I was at a meeting in Santa Fe with a mix of Buddhists from all different traditions, and someone said that we get so caught up in identifying corruption—money, sex, power—that we’ve lost sight of the real corruption in Buddhism, which is the way the teachings are being altered to make them palatable to an American sangha. I fully agree. That is, if you mean making the practices easier or less disciplined. Then there are other corruptions as well, such as the appropriation of fundamental elements of Zen training by psychotherapists who give them a psychological twist. Or you find therapists teaching their patients meditation and equating it with spiritual liberation. Another threat to the integrity of Zen, and in many ways the most bizarre, is that of Zen teachers sanctioning Catholic priests and nuns as well as rabbis and ministers to teach Zen. However, there is another corresponding danger. Those of us who call ourselves Buddhist corrupt the teachings by a narrow sectarianism and by a sort of withdrawal from what’s going on in our society. A great Zen master warned, “The man who clings to vacancy, neglecting the world of things, escapes from drowning but leaps into the fire.”

Why is sanctioning clergy from other traditions so problematic? For example, there is a book, The Practice of Zen Meditation, by Hugo La Salle. Father La Salle was a very good friend of mine, but if you read this book you’ll find that one of its main purposes is to show that “everything in Zen Buddhism we have in Christianity.” Father La Salle frankly admits that the purpose of the book is to prove that.

Is there an intrinsic contradiction between a theistic tradition and Zen? I would say so. Zen has a different flavor and history than either Judaism, Christianity, or Islam, and of course Zen Buddhism does have its own unique methods for attaining awakening.

Does awakening manifest itself the same way in all traditions? No, it doesn’t. Enlightenment doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it manifests in a body/mind. Depending on the spiritual, physical, and mental training one has received, the effects of that training will show in the bearing and actions of the practitioners. When I was in Japan, I would see a Zen person and a Pure Land person walking side by side. The Zen man would be walking from his tanden or hara (four fingers below the navel). He would be erect without being tight, would be walking, not from the shoulders and the head but from the hips. And there are other things that one would notice about the Zen person. The Pure Land sect, on the other hand, puts a great emphasis on faith, and so the Pure Land person has more of a humble attitude. In Pure Land, usually, there is no sitting meditation as we know it. And so the kind of person it creates is different. I’m not saying that the Zen person is superior. The kind of humility that many Pure Land people have is something that Zen people would do well to acquire because—let’s be honest—many Zen people have a certain arrogance. There is a difference in the way people will manifest the kind of training that they have received, for better or worse. Pure Land followers have faith in the saving power of Amida Buddha. It is called “other power.” Zen, evenbompu, is called “self-power.” Everything depends on what you want to get out of it. There is what is called the lowest level bompu Zen where there is no religious or philosophical content involved, simply meditating.

What does “bompu” mean? It refers to “common” Zen, so we say “common person” Zen—a person who has no religious or philosophical orientation, who simply wants to improve physical and mental health. There are different levels of Zen. At the highest level it’s about enlightened awareness. At the lowest, it isbompu.

So ordination for you represents a way of maintaining the full spectrum of the Zen tradition? Yes, when you become ordained you take a vow to protect the tradition and the teachings; both are important. And the ordained’s vow is to devote his whole life to developing his moral and spiritual potential so as to be able to help others. That is why I feel that an ordained individual can be entrusted with these teachings more than a lay person.

Yet all of the Zen teachers who have created havoc in their own communities over issues of money, sex, power, or alcohol have been ordained. It is true that all of the Zen teachers who have caused upheaval among their followers have been ordained. But remember, we were talking about the corruptions of the dharma, and of corruptions they have not been accused of. If these roshis had been genuine Zen masters, they would have been able to withstand the temptations to which they had been subjected. There is something lacking in a system of dharma transmission or sanction that places moral behavior low on the list of qualifications of a teacher. Finally, in a karmic sense all of us, to a lesser degree, are responsible for what happened because all of us helped to shape and are a part of our materialistic sex-oriented society. To keep a proper perspective, although this does not justify the behavior of these roshis, it should be pointed out that lapses in moral behavior are not confined to teachers in the Zen sect or in Buddhism generally.

Are there useful guidelines that a student can use in selecting a teacher? If he or she has little or no experience along these lines, it is most helpful to enlist the advice of older friends who know many teachers. Most important, try to meet senior students of the roshi to observe their manner of relating. All teachers can be judged by the quality of their senior students. But ultimately new students must use their own experiences in evaluating people.

Might you have any particular advice for a young woman looking for a Buddhist teacher? Get thee to a nunnery! (Laughing)

What is the best way to diminish the possibility of sexual abuse in the Zen sanghas ? The best protection is for a student to be careful in his or her selection of a teacher, and for the teacher to be cautious in deciding whom to sanction as teachers—to be sure of the moral as well as the spiritual qualities of that person. But there are no guarantees in either case. The trouble is that most would-be students are often lazy or unaware of their responsibilities in such a highly important matter. Choosing a spiritual teacher is a very serious problem, and one should devote the kind of time and effort to it that one would devote to any fundamental problem in life.

Should the sangha define the terms of enlightenment? Part of the problem comes from our great emphasis on individuality. In Japan when you have meetings, it is taken for granted that beginners keep their mouths shut. At our meetings in Rochester everybody acted as equals. Was it Plato who said, “Every jackass has a right to give his opinion”? Of course, he said it sarcastically. There is no humility, and that may be due to the great emphasis on individuality in this culture, which of course has its positive sides, as we well know. There will always be certain people who will complain. Generally speaking, I admit that a teacher needs to have some room. And those of us who’ve trained in Japan tend to be impatient. But there does come a point where the teacher has to be held accountable. And the senior students are the ones who have to be responsible for making the teacher accountable. But I want to emphasize one thing: Zen Master Dogen said, “The teachings of Zen are not nearly as important as the methods of Zen training.” This is very important because what is unique to Zen are the methods for attaining awakening. Unless people have gone through these methods, particularly in a Zen monastery with a good teacher, they don’t really know what Zen is.

Can the methodology be separated from transmission? One who trains under an authentic Zen teacher inherits a whole line of teaching going back to the Buddha himself. These methods have been handed down from teacher to teacher. Each one has devoted his or her whole life to that tradition. Someone who truly becomes a personal student of the teacher inherits a long line of great Zen masters’ discoveries of the human mind. It’s one thing to practice to get some relief from anxiety, to calm the mind—all of which is certainly legitimate—but it’s practicing Zen on a very superficial level. From the Zen Buddhist point of view this is a very low aspiration. The highest aspiration is the desire for awakening.

To what extent is this preservation of Zen method dependent on monasticism? Earlier we spoke of some of the corruptions of Zen in this country, and probably elsewhere in the West. Now if we had in this country Zen monasteries with able abbots dedicated to the preservation of Zen’s unique teachings and training methods, we could be assured of the survival of Zen. Unfortunately, there are no such places—yet.

Do you think it’s impossible to maintain the intensity of the Zen tradition within a secularized format?That’s the crucial question. Given the drift toward secularization that we are now witnessing, and the corruptions of Zen now taking place, I seriously question whether we can do so. A certain amount of change is inevitable. But change or modifications that are in accord with our own cultural needs are one thing, corruptions are another.

Is a celibate sangha of benefit to maintaining and transmitting the teachings? Yes, a celibate sangha could be of benefit in maintaining and transmitting the teachings if it had a genuine monastic setting. Since the celibate monastic has no obligations to family, to wife, or to children, he or she is, in theory at least, able to devote himself wholly to studying and learning and preserving and transmitting these teachings. But in practice it hasn’t worked out that way. In our “obsexed” society, the celibate is regarded as weird.

Do you have a group of celibate ordained teachers now? In the beginning we did, but eventually they all returned to lay life. Mixing with sexually active members proved to be too hazardous for the celibate monks.

Would you like to see Rochester develop a monastic community? When I first came to Rochester, one of my fondest hopes was to be able to establish a Zen monastery. For many reasons, perhaps because of my own inadequacies, it never materialized. Since I am no longer in Rochester and am semi-retired, such thoughts no longer enter my mind.

Would you be in favor of some kind of national institutionalization of Zen training, so that teachers could be de-licensed or debarred, the way a lawyer would be? If it would reduce the abuses of power, yes. Self-regulation would be better, of course, but the trouble with self-regulating bodies is that they often become more interested in helping preserve the status of the transgressor than in protecting the public. But, then bureaucracies also tend to become more interested in preserving their own authority than in the matters they were set up to oversee. I think it’s important not to get too didactic about this.

Another issue that lends itself to dualistic thinking—and has been one theme in your teachings—is vegetarianism. I prefer not to use the word vegetarian because it is much misunderstood. When people ask me if I’m a vegetarian I say, “No, I’m not a vegetarian—it’s just that I don’t eat animal flesh.” In the minds of most people the word vegetarianism conjures up the diet of a rabbit. This whole subject is much larger than whether Buddhists should for reasons of religion eat meat or not eat meat. Taking life is contrary to the first precept and indirectly supports the killing of animals. Consider: one-third of the world’s grain harvest is fed to livestock while millions of humans go hungry. In 1984, when thousands of Ethiopians were dying from famine, Ethiopia continued growing and shipping millions of dollars worth oflivestock feed to the United States and other European countries. Forests teeming with life explode in flame to create cattle pastures, water tables fall, and fossil fuels are wasted in the U.S. Each of these cases of environmental decline issues from a single source—the global livestock industry. The problem affects the whole globe. Our very survival is at stake. And also, a real connection has been established between cancer and other degenerative diseases and the eating of flesh foods. We not only hurt ourselves but we hurt everybody else when we eat flesh foods. The world is one interrelated, seamless whole.

When we look at an illness like cancer, which is at least in part an environmental issue, can we understand it in terms of collective karma?Yes, individual karma and collective karma often overlap. The eating of flesh foods is by no means the exclusive cause of these diseases, but medical opinion has established a connection. We must be very careful not to be simplistic about these matters. There are so many intangibles. We all have a certain amount of personal responsibility but there are factors over which we have no control, and so we must be careful how we interpret karma. There was a tragic accident that occurred in Japan while I was there training with Yasutani Roshi. Two trains coming from the opposite directions somehow got on the same track and collided. Many people were killed, many were seriously injured, and there were some who were not injured at all. Here again we see the operation of collective karma and individual karma.

A discussion arose about this accident, since three people who were present had been on one of the two trains. The question of karma came up, and it was clear that from an ordinary legal standpoint the engineers of the two trains who had ignored certain signals or overlooked them were responsible for this terrible accident. Then Yasutani Roshi astonished almost everybody there by saying, “Every person who got onto one of those trains freely, who wasn’t being compelled to go on, but freely placed himself on one of those trains was at least fifty percent karmically responsible for what happened to him or her.” And I remember these three people who had been on the train asking how can they possibly be responsible karmically when they did absolutely nothing to cause that accident. Yasutani Roshi held his ground. He said, “I can only repeat: if they voluntarily got onto those trains, they are karmically responsible for their injuries or their death.”

Do you see your own illness in terms of consequence? Yes. That’s why I never bitterly asked, as so many people do, “What have I done to deserve this?” The answer’s got to be: “Plenty!”

How have the teachings of rebirth, reincarnation, the unborn, the undying informed the way you’re looking at your own life, your own death? Normally, I don’t think very much about my own death, but I was obliged to when my Parkinson’s was diagnosed. I actually thought I was going to die, and there wasn’t fear but more curiosity than anything else. I wondered what was going to happen next and looked forward to an entirely new experience. The teachings of karma and rebirth, if understood properly, can be greatly reassuring—not only when you’re actually facing death but at other times in your life, such as a very painful illness. The aim of the Buddhist is not rebirth. The ultimate aim—if one has an aim, and at some point, of course, one does—is how to transcend the body with its pains and sicknesses, so that one achieves pure consciousness. That’s very hard to imagine.

Life and death, as my teacher used to point out, are just different names for different states. These are not permanent states. If we have to give it a name, Life with a capital “L” is the basic reality. Ours is not an inert universe, it’s an alive universe; so what we call birth and death are just temporary states, temporary transformations, names for our true self at one time, and in one situation. One who has glimpsed this acquires cosmic view. Speaking from the Absolute standpoint, we’re all immortal. We know from Buddhism—and science certainly confirms this—that there are innumerable universes. I remember one issue ofNewsweek which said scientists were going to launch a program to find out whether there is meaningful life—human life—on another planet. As part of the project a dozen artists were asked to picture what kind of bodies these beings would have. That was revealing because nowhere was it suggested that there could be life without a body, just pure consciousness.

You may remember that when the Buddha was dying and his disciples were crying, he scolded them, saying, “Now when this body, which harbors so much ill, is on its way out, now that the dreadful dangers of becoming are about to become extinct, and I will emerge from endless suffering and come to a state which is beyond any imaginable bliss and contentment, is this the time for you to be crying? You should be laughing with joy.”

The teachings don’t affect the physical pain? There was a Zen master who, when he was dying, was shouting and carrying on, moaning and groaning. One of his disciples asked him, “Master, how can you be going through all of this pain, somebody who has your spiritual development?” The master replied, “My groaning and moaning is just another name for my laughter.”

Do you ever have experiences where you become afraid of the passage ahead? So far I haven’t. I don’t know what’s going to happen in the future.

Did your illness correspond to any adjustment in how you understood the teachings? No, because I knew that what I did, or did not do, reflected my karma. I didn’t blame anybody. Buddhism teaches that the principal reason for birth is not the will of our parents, that’s a secondary reason: the parents provide a body. The primary reason is one’s own desire to be reborn. As someone put it: “The will to live makes man re-live.”

Looking back on your experiences and the choices you made about bringing Zen to this country—are there things you would do differently? No. As I said, what I did reflected the working of my karma at the time. When your karma changes, so do you. I feel very grateful and I absolutely have no regrets. How can I?

When The Three Pillars of Zen appeared in 1965, it had a monumental impact on the direction of Buddhism in North America. Compiled by Zen teacher Philip Kapleau, it combined a series of talks for beginning students by Yasutani Roshi with classic Zen texts. Most important, it offered the first how-to instructions for Western practitioners; after a decade of widespread interest in Zen—generated by the books of D. T. Suzuki and Alan Watts—no longer could an American read about Zen and not know where to begin.

Kapleau Roshi was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on August 20, 1912. During the Depression, he went to night school to study law with money earned as a court reporter, but had to quit for health reasons. His reporting skills led to his military assignment, in 1946, to cover the Nuremberg war trials. From Germany he applied for a transfer to Tokyo, where the war trials were just beginning. There, Kapleau was struck by the difference between how the Germans and Japanese were handling their defeat and became determined to understand the laws of karmic retribution by which the Japanese accepted the ravages of war as payment for the harm they had initiated.

From 1953 to 1965, Kapleau trained in Japan, primarily with Harada Roshi, Yasutani Roshi, and Soen Roshi, three of the most respected Zen adepts of this century. On returning to the United States, he founded the Zen Center in Rochester, New York.

A few years ago, Kapleau Roshi developed a mild case of Parkinson’s disease. Today he lives in Hollywood, Florida, where he continues to lead workshops and work with individual students. The Center in Rochester continues to thrive under the leadership of his successor, Bodhin Kjolhede.

In 1990, Doubleday published a twenty-fifth anniversary edition of The Three Pillars of Zen. To date, it has been translated into twelve languages and has sold almost a million copies. It remains one of the most influential and inspiring Zen books in the West.

This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Helen Tworkov at Kapleau Roshi’s residence in Hollywood, Florida in March, 1993.

The Three Essentials of Zen Practice

Hakuun Ryoko Yasutani Roshi

WHAT I AM about to say is especially applicable to daijo Zen (or the Great Vehicle), which is specifically directed toward satori (enlightenment), but it also embraces saijojo (or the Highest Vehicle, characterized by an absence of striving for enlightenment), though in a lesser degree.

The first of the three essentials of Zen Practice is strong faith (daishinkon). This is more than mere belief. The ideogram for -kon means “root,” and that for shin, “faith.” Hence the phrase implies a faith that is firmly and deeply rooted, immovable, like an immense tree or a huge boulder. It is a faith, moreover, untainted by belief in the supernatural or the superstitious. Buddhism has often been described as both a rational religion and a religion of wisdom. But a religion it is, and what makes it one is this element of faith, without which it is merely philosophy. Buddhism starts with the Buddha’s supreme enlightenment, which he attained after strenuous effort. Our deep faith, therefore, is in his enlightenment, the substance of which he proclaimed to be that human nature, all existence, is intrinsically whole, flawless, omnipotent—in a word, perfect. WIthout unwavering faith in this the heart of the Buddha’s teaching, it is impossible to progress far in one’s practice.

The second indispensable quality is a feeling of strong doubt (daigidan). Not a simple doubt, mind you, but a “doubt-mass”—and this inevitably stems from strong faith. It is a doubt as to why we and the world should appear so imperfect, so full of anxiety, strife, and suffering, when in fact our deep faith tells us exactly the opposite is true. It is a doubt which leaves us no rest. It is as though we knew perfectly well we were millionaires and yet inexplicably found ourselves in dire need without a penny in our pockets. Strong doubt, therefore, exists in proportion to strong faith.

I can illustrate this state of mind with a simple example. Take a man who had been sitting smoking and suddenly finds that the pipe which was in his hand a moment before has disappeared. He begins to search for it in the complete certainty of finding it. It was there a moment ago, no one has been near, it cannot have disappeared. The longer he fails to find it, the greater the energy and determination with which he hunts for it.

From this feeling of doubt the third essential, strong determination (dai-funshi), naturally arises. It is an overwhelming determination to dispel this doubt with the whole force of our energy and will. Believing with every pore of our being in the truth of the Buddha’s teaching that we are all endowed with the immaculate Bodhi-mind, we resolve to discover and experience the reality of this Mind for ourselves.

The other day someone who had quite misunderstood the state of mind required by these three essentials asked me: “Is there more to believing we are buddhas than accepting the fact that the world as it is is perfect, that the willow is green and the carnation red?” The fallacy of this is self-evident. If we do not question why greed and conflict exist, why the ordinary man acts like anything but a buddha, no determination arises in us to resolve the obvious contradiction between what we believe as a matter of faith and what our senses tell us is just the contrary, and our zazen is thus deprived of its prime source of power.

I shall now relate these three essentials to daijo and saijojo Zen. While all three are present in daijo, this doubt is the main prod to satori because it allows us no rest. Thus we experience satori, and the resolution of the doubt, more quickly with daijo Zen.

In saijojo, on the other hand, the element of faith is strongest. No fundamental doubt of the kind I mentioned assails us and so we are not driven to rid ourselves of it, for we sit in the unswerving faith that we are inherently buddhas. Unlike daijo Zen, saijojo, which you will recall is the purest type of zazen, does not involve the anxious striving for enlightenment. It is zazen wherein ripening takes place naturally, culminating in enlightenment. At the same time saijojo is the most difficult zazen of all, demanding resolute and dedicated sitting.

However, in both types of zazen all three elements are indispensable, and teachers of old have said that so long as they are simultaneously present, it is easier to miss the ground with a stamp of the foot than to miss attaining perfect enlightenment.

This excerpt from Philip Kapleau Roshi’s The Three Pillars of Zen (Anchor/Doubleday) is an English translation of a talk by Yasutani Roshi.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.