As a young man growing up in Italy, Khyentse Yeshi Rinpoche, son of the famous Dzogchen master Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, was the embodiment of many things, chief of which were conflicting emotions and views about his mostly absent father. “I’ve always had dreams, since I was 5 years old—strange visions—and I was really scared about this,” says 18-year-old Yeshi in the opening scene of My Reincarnation, a remarkable documentary by Jennifer Fox about the complex, changing relationship between father and son, filmed over three decades of their lives. “So I asked my father—but he is not answering.” Indeed, Yeshi, born in 1970 in Italy to an Italian mother and identified in infancy as a tulku, or reincarnate lama, had a lot of questions about his role in the world, but the master never offered an overt response.

The film plumbs a variety of reincarnations: Namkhai Norbu, too, was identified as a tulku at the age of 5 and whisked from his family to a rigorous life in the monastery. But shortly after finishing his training, he fled the Chinese occupation of Tibet (news that his entire family and many of his teachers were killed came nearly 20 years later) and “started from zero,” teaching Asian languages in Naples. Then there is the matter of Yeshi’s being the reincarnation of Namkhai Norbu’s uncle, a master named Khyentse Rinpoche Chökyi Wangchug, who was murdered in a Chinese jail in Tibet.

The driving story in My Reincarnation is how Yeshi resists, rejects, and ultimately embraces this inheritance in a surprising turn of events. But woven in and around the literal rebirths are the various metaphorical incarnations of these two people—as Tibetan refugee and bicultural first-generation Italian; as father and son; as teacher and student; as young man maturing and mature man growing old. In contrast to his son’s perception, Namkhai Norbu is renowned among students for his informal style and how accessible he makes the teachings of Dzogchen, or “great perfection,” an esoteric approach to perceiving the nature of mind. In a stand against convention, he does not send his tulku son to a monastery in India to train as a lama. “I didn’t want to condition Yeshi,” he says. “If he is the real incarnation of my uncle Khyentse, we should see how he manifests.”

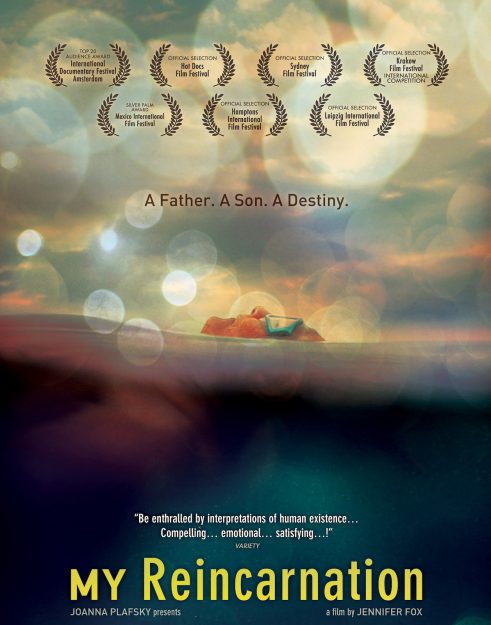

Fox, a student of Namkhai Norbu, began filming the family in the late 1980s while working as the teacher’s secretary. Her insider’s view, and her sensitivity and light touch as a director (she has two award-winning documentaries under her belt), lets the extraordinary situations of these men’s lives speak for themselves. Through deftly edited interviews overlaying intimate, sometimes rough, footage of the master and son (at home in Italy or at the centers Namkai Norbu has founded to preserve and promote Tibetan culture and Buddhism; in Massachusetts, Baja California, and Russia), Fox sketches a sort of triptych: the film is arranged in three chronological chunks that reveal the personal and spiritual transmigrations of each man. Mid-film, in footage shot in the early 2000s, we see Namkhai Norbu overwhelmed by the unwieldy growth of his popularity and the Dzogchen centers mushrooming under his auspices, and soon he is also overwhelmed by a serious illness. Yeshi grapples with this new incarnation of his father as a weakened man—“I always saw my father as a strong person, a strong character”—and with how to come to his aid. “To be helped, he needs someone who is similar to him,” Yeshi speculates. “What kind of help can I give him? Only problems.”

It is here, in this gully, that both men find a new road into the dharma that in turn leads them out of their personal spiritual impasses and the seeming stalemate of their relationship. Namkhai Norbu becomes disenchanted with his own negativity in the hospital: “I cannot be thinking only of dying. Then I start to do practice. Mantras and dream night yoga…and [lying in] the water, integrating the elements.” (Shots of Norbu swimming—alone and, later, with his son—are a delightful leitmotif in the film). Within a month, Namkhai Norbu is better. For Yeshi, a burgeoning samvega (dismay) with the stress of corporate life and worries about his aging parents bring about a sea change: he begins to practice during his long driving commutes. “It was very easy—basically: you put in a CD and do “Song of the Vajra” a hundred times, or something like that,” he explains. “I started working differently. I was giving less importance to most of my ideas, [and] I was a lot less stressed when I came back home. I became more efficient.”

Through the merging of his professional training and his growing belief in the dharma, Yeshe finds his own means for taking on the obligations of the spiritual lineage he has fended off for so long: he becomes the man who can help his father. He begins to apply leadership skills—“normal knowledge from the business world”—to the flailing Dzogchen organizations that have Namkhai Norbu stumped and distraught, and while we don’t see specific results in the movie, Fox conveys a sense of energy and progress. In one scene, Yeshi chides a group of Muscovite practitioners trying to organize a large retreat with no one in charge. “This is wrong,” he tells them. “You need at least one person who knows everything, who can communicate with all these people, who can fail, who can make mistakes… who can be called 24 hours a day.”

Through the merging of his professional training and his growing belief in the dharma, Yeshe finds his own means for taking on the obligations of the spiritual lineage he has fended off for so long: he becomes the man who can help his father. He begins to apply leadership skills—“normal knowledge from the business world”—to the flailing Dzogchen organizations that have Namkhai Norbu stumped and distraught, and while we don’t see specific results in the movie, Fox conveys a sense of energy and progress. In one scene, Yeshi chides a group of Muscovite practitioners trying to organize a large retreat with no one in charge. “This is wrong,” he tells them. “You need at least one person who knows everything, who can communicate with all these people, who can fail, who can make mistakes… who can be called 24 hours a day.”

It is rare for a dharma student to paint such an unvarnished portrait of her teacher, but Fox’s film is strikingly honest in its portrayal of each man’s bewilderment and sense of loss at different points. In one wrenching scene, a student with HIV asks desperately for help, and Namkhai Norbu recommends that he seek good medical advice and do practices to help him relax. “Buddha said, ‘Everything is unreal, just like a big dream.’ Problems are relative. Do not give [it] so much importance.” The camera lingering on the master’s face after the student departs leaves us to wonder: is he satisfied with his response or with the little he can offer one of his thousands of students in a 45-second interview?

By the film’s end, we see a markedly different Yeshi: he seems lighter, content in his own fatherhood, and optimistic as he takes his place in the Dzogchen community. He still puts questions to his father about practice (especially about dreams, an important component of his father’s practice) and customs. “I ask him,” Yeshi says laughing, “but he never answers.” Whether Namkhai Norbu is taking the Buddha’s cue to put aside questions that will lead a student into a “thicket of views,” or whether he wants Yeshe to probe his own mind for the answers, we can’t be sure. The beauty of this graceful and deeply human film is how it makes clear that meditating on these questions for ourselves is part of our path, too.

♦

My Reincarnation opens on October 28 in New York at Cinema Village (22 E. 12th Street, Manhattan) and in Los Angeles at Laemmle’s Monica (1332 2nd Street, Santa Monica).

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.