Since my sister began medical school last fall, she has spoken constantly about an obese female corpse she refers to as “my cadaver”: “She’s so fat, it’s hard to find the nerves and muscles. You have to do a lot of poking around.” Or, “When we first opened her up, there was still shit in her intestines. Can you believe that? She died two years ago!”

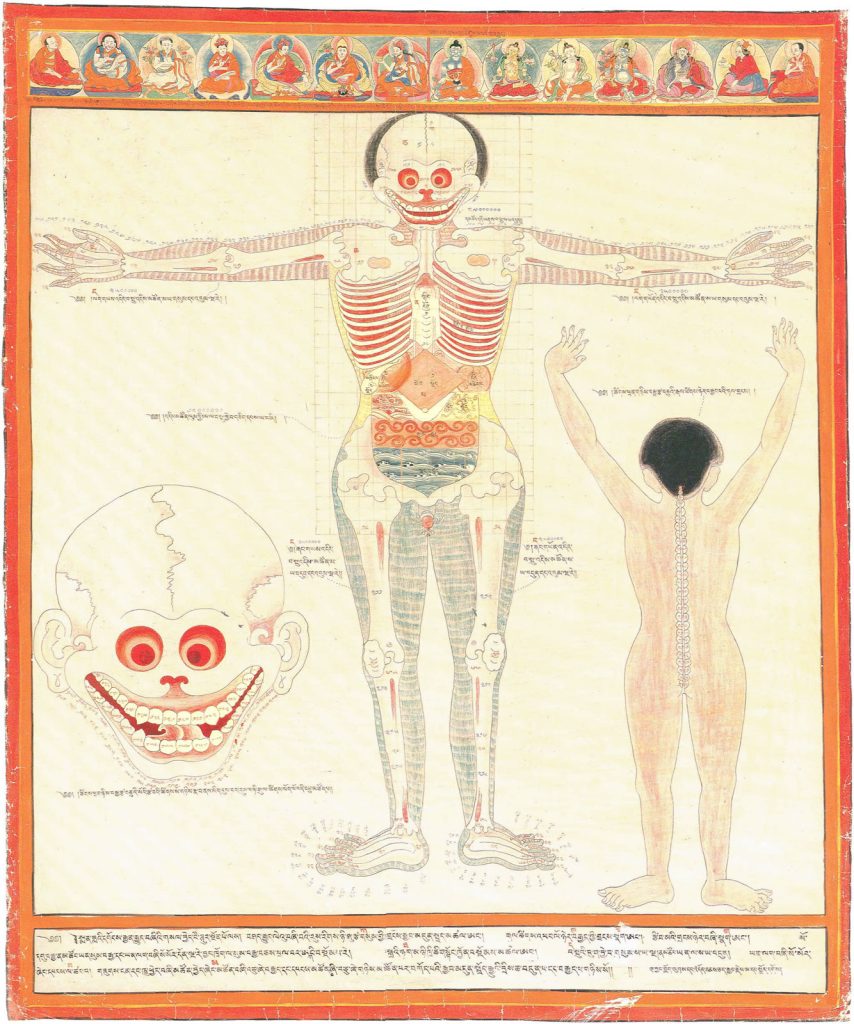

Although I was amused (and occasionally disgusted) by my sister’s eagerness to share every new detail about this dissected body, I was also bothered by her apparent remove. After all, this had once been a person. It reminded me of the “Reflection on the Repulsiveness of the Body” from The Foundations of Mindfulness (Satipatthana Sutta), in which the Buddha taught his followers to contemplate what we’re made of: “the contents of the stomach, feces, bile, phlegm, puss, sweat, solid fat, tears, fat dissolved, saliva, mucus, synovial fluid, urine.” And when he had a captive audience at the cemetery, his descriptions got really vivid: monks were to meditate on “a body dead one, two, or three days: swollen, blue, and festering” and “blood-besmeared skeletons . . . eaten by crows, hawks, vultures, dogs, jackals, or by different kinds of worms.” The list goes on and on. Monks were instructed to consider that their own bodies would someday meet the same fate.

It wasn’t the gruesomeness—in either these descriptions or my sister’s—that I objected to, but the revulsion they expressed. I was particularly put off by the fact that these meditations were used as a tool to fight lust, being a rather lustful nineteen-year-old myself when I first read them. Okay, I get it, I thought, the body is impermanent; the body you’re now attracted to will someday be a stinking mass of rotting flesh—but do we have to find it repulsive? I could see nothing wrong with praising and enjoying the body.

I went to visit my sister at school for the first time recently, and naturally she wanted to give me a tour. She showed me the lecture hall, the interfaith meditation room, her large wooden locker filled with dirty scrubs. “Oh, and the cadavers,” she remembered brightly, as if it were just another lab or classroom. The room was cold—to keep the bodies from rotting—and windowless. There were about twenty of them, all covered in dirty white plastic. A couple of charred bones floating in the Ganges were the closest I’d ever been to a dead body. At first, I had the feeling that we were not alone in the room, which is what most of us have come to expect from a body—that it equals a person. I felt the urge to pray. I felt the urge to flee. I felt like a voyeur.

And then she lifted the plastic off a body, and suddenly all that went away. It was surprisingly easy to look at, like the plastic model skeleton that was wheeled from classroom to classroom in elementary school—as inhuman as that, but a thousand times more interesting. A surgeon’s cut ran from the skull to the perineum, which allowed my sister to show me the parts. She peeled open the thick, rubbery flaps of skin and lifted up a baseball-sized heart. She dug around in the tissue of the upper arm until she found a nerve, which looked like a thick pink rubber band. “Isn’t this amazing?” she said. “This is how you know to move your hand.” It was hard to find the interesting parts among the excessive fatty tissue. “Jeez, this one’s even fatter than my cadaver,” my sister observed helpfully, so we moved along to another one.

She showed me brains, blackened lungs, ovaries, biceps. The intricacy and self-sufficiency of it all was what struck me most—that we’re carrying around all these various parts, nestled in just the right places, carrying out their specific tasks as we go blindly about our business. These bodies were machines; however miraculous, they had nothing to do with the lives that had once inhabited them. This was true even for the body that had a kind grandfatherly face, perfectly preserved, with white eyelashes and papery skin—I could tell what he once looked like, but he was nowhere near that room. This viewing came at a time when I was excessively concerned with body image, having just moved to southern California, where tank tops and miniskirts are standard attire year-round and first dates often involve a bathing suit. It helped me realize in a concrete way that how we look is not who we are. Ultimately, we have very little control over what happens to our bodies—what they look like, how much pain they’re in, how long they last.

After an hour of viewing the insides of corpses, it was clear to me how narrow my first reading of the cemetery contemplations and reflections on the body had been. In urging his followers to meditate on skeletons and bloody remains, the Buddha was advocating consciousness, not disdain for the body. When we are aware of all the intricate processes and parts that make up our bodies, we are less likely to identify the overall image as “me.” Disdain for our bodies is, in fact, born not of detachment but of identification. When we identify with our bodies, we’re filled with complaints—you might wake up one morning feeling confident and well equipped to face the day, until you step on the scale and see you’ve gain a few pounds; or you might be giddy with excitement for a date until you discover what the humidity has done to your hair.

Of course the flash of dharma I received while viewing the cadavers didn’t prevent me from asking my sister six times if my butt looked too big in a pair of jeans the next day, but at least I was laughing at myself as I did it. I don’t plan to stop wearing clothes I find attractive, or brushing my hair, or looking at myself in the mirror before I go out. This isn’t sixth-century B.C.E. India, and I’m not a nun; using my body consciously has a different meaning for me than it did for the Buddha’s first followers. For instance, being aware of the physical processes involved in lust does not necessarily require me to head to the nearest burial ground every time I feel attracted to somebody. But it does make it more difficult to throw myself into an unhealthy sexual situation. I can say to myself, “Okay, this is just my body having a reaction. It doesn’t mean I want to live happily ever after with this person. It doesn’t mean I should take off all my clothes.” Similarly, it’s difficult to lavish hundreds of dollars and hours and small miseries on beautifying the body if you retain awareness of the rotting flesh it will someday be.

This distance not only allows us to forgive our bodies for their inevitable flaws, but it can also lead us to better care for them. One of the corpses I saw had lungs of blackened soot: a smoker. His heart was a cantaloupe instead of a peach, from pumping so hard to get air to his lungs. His face was sweet, but deep inside, his organs had turned black and swollen. How we treat our bodies does matter, because it matters how we treat everything. In his Instructions for the Cook, Dogen asks us to see a lettuce leaf as the Buddha’s body—to bring the same level of attention and care to making a salad that we would use to interact with the Buddha. We are asked to honor the Buddha’s body, which means honoring the leaf, which means honoring our own bodies, zits, fat butts, and all.

At the end of a med student’s first year, she attends a ceremony in which the students thank the families and loved ones of the bodies they spent the past year slicing apart, shifting around, and dousing with chemical preservatives. The ceremony seemed tacky to me when my sister first told me about it—an oddly personal end to an experience expressly geared at being impersonal. But after seeing the bodies and witnessing firsthand my sister’s relationship to them—a mix of awe and understanding—the ceremony made sense. You don’t have to feel love or attachment to something to honor it. The med students perhaps related to the cadavers in much the same way the Buddha related to his own body—grateful for the experience it afforded them, but free of sentimental attachment. Why not offer thanks for a gift that will never belong to you?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.