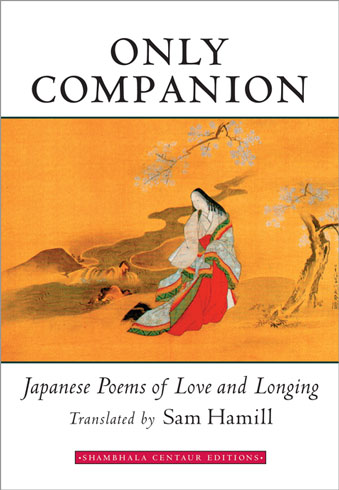

Only Companion: Japanese Poems of Love and Longing

Translated by Sam Hamill, Shambhala Publications: Boston, 1992. 160 pp., $11.00 (paperback).

In his preface to Only Companion, translator Sam Hamill points the way for us to follow, the way by which he found the heart of each of the one hundred poems in this moving collection. He tells us that “the authentic experience of the poem . . . begins with the quality of our listening.” When readers listen deeply, as they must if they are to merge with the world of the poem, they travel the same path the poet took to be captured by the poem in the first place. Authentic writing and understanding are more easily accomplished once we have listened deeply, for listening is the poet’s art.

Listening deeply is the only way Hamill could meet these poets at the origin of their poems and create versions so faithful to the original. But where is this origin? How do we know a poet has been there? Or, as the fifteenth-century poet and Zen master Ikkyu Sojun says in this collection:

And what is mind

and how is it recognized?

It is clearly drawn

in sumi ink, the sound

of breezes drifting through pine.

The poems in Only Companion are rooted in the five-line Japanese form called tanka and span over one thousand years of human expression. But this poetry is most truly rooted in the universally experienced ground of yearning, the simple human longing for connection. Whether these poems were born of the poet’s longing for erotic or spiritual communion, Sam Hamill’s versions are traceless, strong, and with meaning so subtly implied that they draw together the unity of spirit and eros in one uninterrupted breath. In this atmosphere these poets and their lovers or their solitude come and go like sumi ghosts against an empty rice-paper screen. Many of the poems are so still we can hear the heart’s bare echo. Listen, as one anonymous poet writes:

In the high bare limbs

of twisted trees, the moon

slowly awakens

to the soul’s darkest season:

inevitable autumn.

Indeed it is the temporal nature of life itself, the “inevitable autumn,” that serves as the one season unifying these poems. But the feelings expressed are not always disconsolate. Though Saigyo knows he is destined to lie forever

alone beneath a blanket

of cold moss

remembering what is learned

only from dew and stone

He treasures the “sweet loneliness” of his reclusive life where he is able to see the moon’s light “mirrored in the enlightened mind.” And though Muso Soseki cannot find which road will lead him back the way he came, his wandering has taught him “the road goes anywhere/and anywhere at all is home.” As these poems show, the real voice to be heard here, where “only impermanence lasts,” is the plain but poignant voice of ordinary human life and truth. It is a voice that knows this floating world will pass, but even so, it stopped Sogi, a sixteenth-century poet, long enough to tell us:

Everyone’s journey

through this world is the same,

so I won’t complain.

Here on the plains of Nasu

I place my trust in the dew.

Poems such as these are not limited’ by the ordinary constraints of culture and time. Rather, they function in a manner indicated by the great haiku master Basho, who told us:

the temple bell stops ringing

but the sound keeps coming

out of the flowers.

In many of these poems, the essence of the poem’s original sounding continues to sound and resound long after the words of the poem have ended. It is the mark of great poetry.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.