When we talk about death happening every moment, we also might have a natural question: “If I’m continuously being born and dying, then who is it that goes through all these experiences?” Once this body is dead, who has the chance to merge with the mother luminosity? If that chance is missed, who goes on to the next bardo, known as “the bardo of dharmata”? When it comes to reincarnation, who gets reborn? A similar question would be “What is it that continues from lifetime to lifetime?” Or “What goes through the bardos?”

The standard answer to all these questions is “consciousness,” or namshe in Tibetan. The word “consciousness” could mean different things to different people, but the Tibetan language is extremely precise when it comes to describing the mind. Namshe implies that this consciousness is dualistic. For instance, if Rosa sees a mountain, Rosa is here and the mountain is there: they are two separate things. Whatever Rosa sees, hears, smells, tastes, or feels seems like an object separate from Rosa.

This is how things appear to all of us, right? There’s a sense of a division between me and everything else. The experiences keep changing, but I always seem to remain the same. There’s something about me that feels like it never changes. But when I look for this unchanging me, I find that I can’t pin anything down.

I was born on July 14, 1936. My name at that time was Deirdre Blomfield-Brown. I can definitely acknowledge there’s a connection between that infant Deirdre and today’s Pema. I have memories of my childhood. The mother and father I had then are still my mother and father to me, even though they’re long gone. A scientist would say that the baby and I have the same DNA. And of course we have the same birthday. But the interesting question remains: Are the newborn baby and the elderly woman I am today actually the same person?

I still have pictures of myself as an infant and a toddler. If I try hard, I can pick out some ways that child looks similar to what I see today in the mirror. But I also know intellectually that not a single cell of my body has stayed the same. Even at present, every cell and every atom of my body is continuously changing.

I’ve tried long and hard to find a real me that stays the same from year to year—or even from moment to moment—but I’ve never had any success. (This is a worthwhile exercise, which I highly recommend to anyone interested in the mysteries of life and death.) So where does this leave us in terms of the bardos?

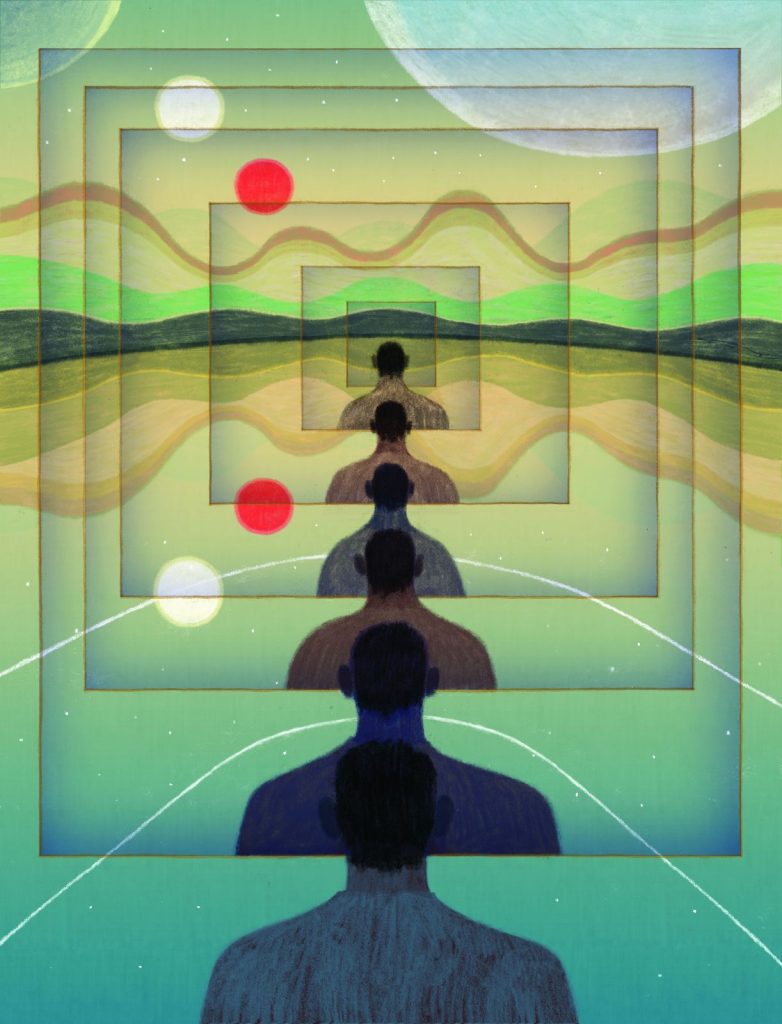

As I said, the standard answer for what continues across lifetimes is namshe, dualistic consciousness. This is not so easy to understand. A while ago, I called my friend Ken McLeod, a highly learned Buddhist practitioner who’s written some of my favorite books, and I asked him about it. Like other students of the Dharma, he said that namshe is what goes through the bardos. But he made the point that this consciousness isn’t some stable entity that flows through everything. It’s constantly dissolving and reforming. Every moment, we experience something new: the smell of toast, a change of light, a thought about a friend. And every moment we have a sense of a self having that experience—a sense of “I, the smeller of toast.” When this moment passes, it’s immediately followed by another moment with a subject and an object. This flow of dualistic experience continues uninterruptedly through our waking hours and our dreams, through this life and across lifetimes.

But beyond this flow of moments, is there anything underlying them all that we could point to as “consciousness”? We can’t locate or describe any stable element that lives through all our experiences. So from this point of view, Ken said that another answer to “What goes through the bardos?” is “Nothing.” There are just individual moments, happening one after another. What we think of as “consciousness” is fluid, more like a verb than a noun.

Life and death, beginnings and endings, gains and losses are like dreams or magical illusions.

When Ken and I had this conversation, it gave me a better feeling for how I keep clinging to this self as something permanent, when it’s actually much more dynamic than that. It’s not some fixed, frozen thing. We can have this view of ourselves as frozen—and we can have frozen opinions of others as well—but that’s just based on a misunderstanding.

Why do we have this misunderstanding? Who can say? It’s just how we’ve always seen things. The Buddhist term for it is “co-emergent ignorance,” or, as Anam Thubten calls it, “co-emergent unawareness.” We all come into our life with this unawareness. And what are we unaware of? We are unaware that we are not a solid, permanent entity and that we are not separate from what we perceive. This is the big misunderstanding, the illusion of separateness.

Here is how I’ve heard teachers talk about the origin of our unawareness. First, there is open space, fluid and dynamic. There is no sense of duality, no sense of “me” separate from everything else. Then, from that ground, everything becomes manifest. If properly understood, the open space and the manifestation are not two separate things. They are like the sun and its rays. This means that everything we’re experiencing right now is a display of our own mind. Recognizing this union is called “co-emergent wisdom” or “co-emergent awareness.” Remaining caught in the illusion of separateness and solidity is co-emergent unawareness.

And this, of course, is where you and I find ourselves. It’s obvious that co-emergent unawareness is our usual experience. But in reality, no one and no thing in our world is fixed and static. Consciousness is a process that constantly dissolves and reforms, both now and in the bardo. And every time it reforms, it’s completely fresh and new—which means that we have an endless stream of opportunities to have a completely fresh, open take. We always have another chance to see the world anew, a chance to reconnect with basic openness, a chance to realize we’ve never been separate from that basic spaciousness—a chance to realize it’s all just been a big misunderstanding.

If you spend enough time pondering this, you might understand it with your rational mind. But then you may still ask yourself, “Why do I experience myself as separate? Why don’t I experience each moment as fresh? Why do I feel so stuck?” The reason you feel this way is that you—like everyone else—have been under the sway of co-emergent unawareness for a very, very long time. Therefore, it takes a very, very long time to dismantle.

Our misunderstanding of separateness goes deep. Even animals have an innate sense of being a separate entity. But unlike animals, we have the ability to contemplate. We can use our fairly sophisticated brains to realize that our misunderstanding is indeed a misunderstanding—that moment by moment, we have a chance, even if briefly, to merge with that basic ground again.

Even if we’re convinced of this, however, we can’t drop our familiar sense of separateness just by willing it to go away. But what we can do is start to meditate. In one session on our meditation cushion, we can see for ourselves how fluid our consciousness is. We can observe how our thoughts and emotions and perceptions appear and disappear, and how this process just goes on and on without a break.

We can also see how mysterious our thoughts are. Where do all those thoughts come from? And where do they go? And why do we get so serious about what goes on in our mind? Even though our thoughts are as elusive as mist, how can they cause us endless unnecessary problems? How can they make us worry, get jealous, quarrel with others, get euphoric and depressed?

Meditation gives us a way to see the slipperiness of our mind and of our notion of “me.” When we practice meditation, we gradually accustom ourselves to how experiences constantly flow. We see that this happens even though we can’t pinpoint any subject who experiences them.

From this point of view, there is no fixed being who goes through the bardos. Another way of saying this is there’s no continuous individual who experiences life and death. No one lives and no one dies. Life and death, beginnings and endings, gains and losses are like dreams or magical illusions.

♦

From How We Live Is How We Die by Pema Chödrön © 2022 by the Pema Chödrön Foundation. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.