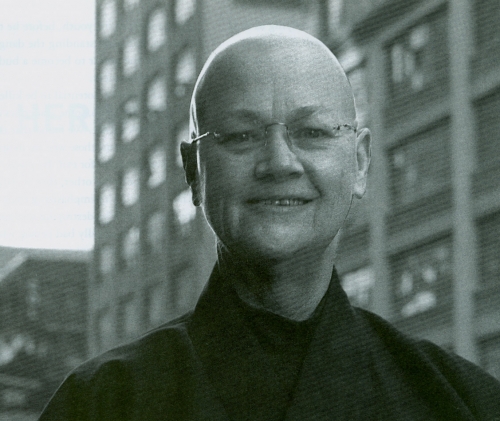

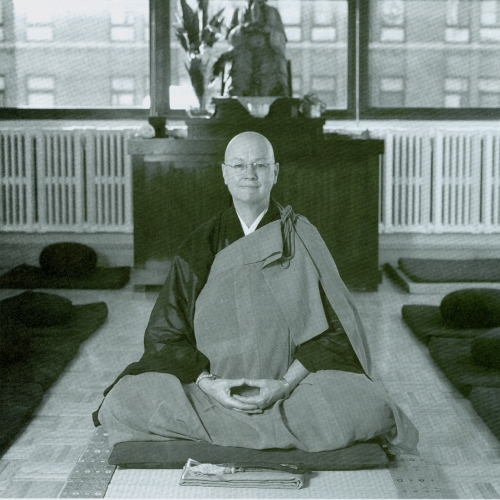

Sensei Enkyo O’Hara is abbot of the Village Zendo, in lower Manhattan. A Zen priest, she is a dharma heir in the Maezumi-Glassman line of the White Plum Asangha of Soto Zen Buddhism. She serves as an elder in the Zen Peacemaker Order, part of an interfaith network integrating spiritual practice with peacemaking and social action. Sensei O’Hara spoke with Tricycle in November 2002.

In the current political climate, a lot of people feel compelled to take a stand in one way or another. As someone who has been engaged in political and social action, how do you as a Zen teacher view taking a stand? In Zen—and I’m not talking about Buddhism, I’m talking about Zen—a primary teaching is that there is no one way. The minute you hold to any one principle to the exclusion of others, you’ve missed the point. The freedom Zen offers is to realize that moment to moment you have to make a decision, so moment to moment you have to decide whether you’re going to march against, say, your government’s policies, or whether you’re going to support them in whatever way you can. But you can’t make a rule, lay down a principle, and say, “This is what Buddhism says about war,” “This is what Buddhism says about this issue or that,” because immediately what arises before you is the other side. This is a very difficult idea to accept: although we all want a path, a right way, we can’t have the kind of certainty we crave. There’s always the other side. And that’s also true about what you think enlightenment is and what you think a good practice-life is.

When you say that you decide from moment to moment where you stand on a particular issue, what is the standard you’re holding yourself to? That question is the heart of the matter. You just have to trust that your practice, your awareness of your oneness with all beings, and your compassion will be activated in each moment. And also know that of course you have to act, and you may not be acting appropriately. There’s always that edge that you’re walking; and the awareness of that edge is very helpful because then you’re not fixed on the notion that you’re right. It’s a hard one, and many people—certainly Zen students and teachers—have made many mistakes. That’s why we have a meditation practice; we have something that allows us to get in touch with the universal, the absolute nature of our being, that allows us to act compassionately.

What do you mean when you say that a lot of Buddhists have made mistakes? What are you thinking of? I’m thinking of the Japanese Zen teachers in my own lineage during World War II, and in particular, Yasutani Roshi. Yasutani Roshi encouraged the Japanese to go to war, and I believe that that was a mistake. There were even others before him who encouraged the invasion of China.

And yet Yasutani Roshi certainly practiced. How do we make sense of that?Again, there is nowhere to stand. I can’t make sense of it. But I can be aware that no matter how clear I think I am, there is another side that I don’t see. There is always an opportunity to look into “the other,” the “enemy,” and discover oneself. How can I explain how Yasutani Roshi got caught up in the patriotic fervor of the time and encouraged killing? Here is a man who had recently completed his formal Zen studies, which teach interrelation, the merging of self and other. And yet he became attached to an idea of self against other. Even more paradoxically, he later became a remarkable teacher.

We all want to idealize our teachers, and we want to idealize enlightenment, and ourselves. What happens is we set things up so that there is enlightenment, and there’s this teacher who’s going to give it to us, and that teacher has to be perfect and we have to be perfect. And of course, it makes it impossible for us to practice, and to have compassion for ourselves and for others. The fact is, we’re all human. And enlightenment does not bestow perfection. There’s no such thing as perfection. There are different teachers with different issues, but always there’s something there. I think of the wonderful teaching of the lotus in the mud: It grows from the muck below and blossoms as a beautiful, pristine flower above. All of us have our feet in the stinking mud, and yet there is an opportunity to offer our lives, however imperfect they are, to others. We can offer our teachings, our compassion.

I think that the most disempowering thing in spiritual traditions is to act as if enlightenment is some sort of perfection and that enlightened people are perfect—and they’re not. My teacher, Maezumi Roshi, was far from perfect, but he was a great teacher. He was intimate, and he was intimate with his own suffering, as well as that of people he worked with.

I guess we would expect to associate enlightenment with perfection, free of flaws. What does it mean then? There’s this wonderful koan that is about just this: “The buffalo passes through the window; his horns pass through, his head, his front legs pass through, his hind legs, but the tail doesn’t. Why is that?” And then the koan’s poem has the line, “So much depends on this precious tail.” [laughs] What doesn’t pass through is that which makes us human and that which allows us to teach, to really reach others. It’s complex, but that’s how I see it.

Can you envision a situation in which it would be consistent with your own view of the teachings to go to war? This is the problem for me: it’s completely hypothetical. I can’t imagine, personally, a situation in which I would encourage people to take up arms; I personally could not do that. When I think of protecting others, for instance, I’m thinking on a very local, individual level, where someone is about to harm someone else, and I might intervene. But to encourage warfare is, I think, an incredibly noncreative solution to very difficult problems.

But the attacks of 9/11, which took place blocks from here, were not hypothetical. Is there a nonviolent response to 9/11 that makes sense? I can only see someone who perpetrates violence as a very damaged human being. As I walked by a newsstand recently, I saw the cover of U.S. News and World Report, which read, in reference to the alleged snipers who not long ago captured the nation’s attention, “Monsters Caught.” I’m not easily affected by things, but I was so hurt: this is a national magazine, and it has reduced these two very tragic men to monsters. Of course, we could go on about Osama bin Laden and a lot of others, but they’re not monsters, they’re people. Very damaged people. I don’t see how you can just say, “Oh, well, violence is the only answer because they’re violent.” It isn’t the only answer when you get past your knee-jerk response. There are many answers, but it certainly does not make sense to deny that human beings did this, nor that we are capable of doing this, nor that they are no other than us. Osama bin Laden calls us evil, George Bush calls him evil, the dualistic split intensifies, and the cycle of violence continues.

And yet we don’t seem to have other answers. What might they be? Alternatives to violence? This is an amazing opportunity to take up the notion of one world, to engage in dialogue with all kinds of representatives—leaders, voices from the street and the basement. It is an opportunity to listen deeply and reconsider our effect on the lives of people living all over the world. For a few moments after 9/11, this country showed its vulnerability and its humanity in its shock and grief. What if that sense had persisted, and instead of gearing for violence we had put all those resources into exploring causes and remedies?

Can you talk about your own social and political engagement in terms of your Buddhist practice? In the sixties I participated, as so many did, out of anger, in demonstrations. I can remember that at one demonstration against the war in Vietnam, I suddenly realized that these young men going off to war were victims themselves. They were not the enemy. This was confusing to me. And so for a few years I stepped back from social activism. I had grown up thinking that there was always an enemy. So to suddenly discover that there was no enemy—but that there was still injustice—was very difficult. At that time I was reading about Buddhism; I wasn’t practicing, I was an armchair Buddhist. I was trying to find answers by reading, but it was only by sitting, and the experience of oneness, and of only taking care of what’s in front of you, that I was finally able to approach activism in a different way.

For instance? I think of the AIDS political action group ACT UP. At a certain point, many of us involved in the AIDS crisis here in Manhattan participated in ACT UP demonstrations. We were demanding that the government respond more aggressively and compassionately to the AIDS crisis. What distinguished ACT UP from so many other organizations was a sense of humor, an irreverence, and more importantly, a willingness to form a direct relationship with the powers that be. In this case the powers were city health officials and pharmaceutical companies.

Demonstrators would go and make a scene that would make people laugh, and cry; the actions were not one-dimensionally hate- or anger-filled. Of course, there was also an element of harboring violent hatred toward those in power, and that made it difficult to participate. But for the most part there was a sense that if we could get people to think, we could get people to change their views.

It was through an interfaith AIDS organization that I was actually involved in negotiations and discovered that it was very helpful for someone like me, who was trained in Zen, to remind everyone that the people we were negotiating with were, after all, just people. You could look them in the eye and just say to them, “Well, how are you feeling about all this?” Just starting a dialogue is really important. So engaging in that way has been where the practice has been most effective.

But when you deal with problems of even greater scale, where contact with the other party is unlikely, there can be an overwhelming sense of powerlessness and anger. How do you act without being subverted by these feelings? That’s a good question. First of all, what if you actually could have a conversation with President Bush? What if you could just talk to him? If you’re so certain that you know everything that’s going to come out of his mouth, you can’t have a dialogue. So that openness is what’s really necessary to begin a political dialogue. If you’re just looking at an “enemy,” there is no chance for dialogue.

Now, as for the powerlessness, that’s a real problem. I will address it from what I know about civics from my school days. I exercise my right to contact my representatives. Very seldom has anyone I’ve voted for won. [laughs] One could become depressed about this.

And yet you have to keep on trying. If it’s your karma to be in a position to make a difference, if you’re able to reach a lot of people, then you should do that. But take a woman with a couple of kids at home, whose world is smaller. She’s not able to do that kind of thing. How does she avoid that sense of powerlessness? Whether she’s writing to the city council or to the school board, in her own way she can act on her sense of responsibility by making her voice heard. Because it is true that if you don’t speak up, you become a part of what’s going on, you’re complicit in whatever it is you disagree with.

Is it näive to think in terms of dialogue when it appears that the opposition—whoever you consider it to be—has no interest in dialogue or political discourse at all? It is our work to find the entry point, because there always is one. It is usually located very close to the injury, whether that is fear of pain, or humiliation, or deprivation.

If someone says the business of Buddhism is enlightenment, and not social and political action, how do you respond? I do believe that the first step is to practice. I see so much anger and emotional violence associated with social action that we need to steady ourselves and take our seat first. Once we have even a taste of the freedom of being a part of everything, of being everything, then we’re not so angry, and social action—however it takes shape—comes naturally, and without anger, and it’s more effective. An old Zen koan says it’s like adjusting your own pillow in the night, responding appropriately, and quite naturally, to the needs of a specific situation. Why are you compassionate? You don’t know why you’re compassionate—you just are, fundamentally.

A lot of anger comes from failed expectations. Is it unrealistic for us to expect that the world be just, or at least conform to our notion of what “just” is? First of all, history is full of warfare and pestilence and starvation. These are part of being alive, and they’re what Buddhism addresses. It’s unrealistic to expect that we’ll live a long and happy life. That’s not the nature of life. Suffering is part and parcel of being alive, and Buddhism teaches us how to be with that, how to react to that, how not to become fixated on some permanent idea of happiness.

Can we understand the why of gross injustice in terms of karma? I don’t know if I’d say this of Buddhism, but I’d say Zen in particular is not very interested in the why of things. Of that I can assure you. Consider the story of the man wounded by an arrow while demanding to know the specifics of his case—who shot the arrow, what sort of arrow, what type of poison it had been dipped in, et cetera—before he was willing to address the issue at hand. All the while, he moves closer to death.

But Zen can tell you how to work with the suffering you experience. A lot of people I see every day have been living with fear since 9/11, especially here, downtown, just blocks from Ground Zero. This kind of death has been going on all over the world, and continues even now, but it’s new here in Manhattan. When someone comes into dokusan [in Zen, a private interview with the teacher] and asks, “Why did this happen?” I’m not going to address that. I’m going to ask, “Where are you feeling the fear that you’re feeling right now? Can you show me that fear?” It comes down to “Where are you right now?” A woman told me a couple of days ago after a memorial service for her father that the fear of her father’s dying was much, much greater than her experience of grief. She had this huge fear, and then he died, and there was just grief. It’s like the fear of a terrorist attack in Manhattan; it paralyzes people. What do the teachings tell us? We have to be one with it. And to realize, yeah, life and death, they’re two sides of the same coin. At any moment we may die—it’s always been this way, and that’s why we have to practice, to be able to face that.

Would you say that fundamentally nothing’s changed, then? Well, the same principles apply. We can go at any moment. So the fear—and it’s fed enormously by the media—is of what we’ve always been dealing with, and our own death. The issues are the same, but our perceptions may have changed.

Your temple is one of the closest to Ground Zero. How has your sangha changed? There’s more political awareness and participation in peace walks, et cetera. The fear has ebbed a bit, and at the same time, there’s a lot of anxiety about our economic prospects. So on the one hand, it’s concern over matters of life and death, and on the other it’s “Am I going to have what I need?” It’s “I’m alive now, and I want to stay alive, and I’m able to make it financially now, but I’m terrified that soon I won’t.” That anxiety is really extra. It stops you from staying in the flow, staying alert to opportunities when they do arise.

How do you relate those fears, those anxieties, to ego attachment? Well, the obvious attachment is to one’s own life, an unwillingness to acknowledge one’s own mortality. And it’s attachment to what you perceive that you have in this moment. So you’re holding on to something, as if holding your breath. Of course, you have to exhale at some point, to let go in each moment.

Zen teachers are very fond of saying there are no obstacles, only opportunities. What opportunity did 9/11 offer? In very clear ways, people did benefit. In particular, during the last year, many people have begun chaplaincy training in hospice work. Before, we had maybe one person. Now, we have over eighteen people studying chaplaincy. Why is this? They’re being drawn to really tasting that sweetness at the very end of life. How do you work with someone who is dying, and how do you let that person’s situation into your own heart? You can’t do it unless you’re at least aware that death is right here at every moment. So I think it’s on a gentler, individual level that the sangha is changing and growing spiritually.

Have you seen an influx of new people? Yes, especially young people. Just the other night we had a group of students from the New York University dorms nearby, a group of friends who just decided to come and start sitting. You know, when you’re young, you don’t think you’re ever going to die, or get ill, or get old, or ugly, or bald. [laughs] 9/11 is waking up some very young people. And the way they wake up is that they seek out some kind of tradition that will allow them to face their own morality and deal with their own life situations as they are right here now.

During difficult times, historically, Buddhist teachers have retreated from society, eluding repressive governments or chaotic societies, finding some mountaintop to sit on. But they were part of a culture that did not allow for public dissent. So a lot of Zen history implies that going off to a mountaintop, or sitting in meditation, may be the highest form of social action, in terms of benefiting all sentient beings. What does it mean to us, in a democracy, to have the option to do something else, to make our voices heard, something we’ve been trained to consider an obligation? There are those stories in which Zen teachers who were intimate with governing authorities did exercise influence to the common good. And yes, most did go off into the mountains, but it doesn’t mean they did nothing. They planted trees, raised animals, built orphanages, and provided refuge for political exiles. There was a whole range of social activity that took place in these old, isolated Zen monasteries. But, as you say, we are Western Buddhists, and we’re taught that we can make a difference by speaking up directly. And so we have to speak up; we’re a part of the whole tradition in this country of taking social and political action. But I don’t see a great contradiction here.

It’s simply that in China they didn’t have much of an effect on their government, which simply means they had an effect on whatever they could have an effect on. So in their case, they took care of things up in the mountains. “Why are you planting trees?” Isan was asked. Isan answered, “I’m planting trees for the valleys and for future generations.”

In this country, many of the great dissenters have come from the Judeo-Christian religious communities. And so naturally, now that there are Buddhists in this country, we also speak up, from our own communities. I was first drawn to Zen because “ordinary mind” is the way. Where you are is where you practice. I suppose if I had not chosen to practice in Manhattan but had chosen some beautiful mountaintop monastery somewhere, my views might have been different than they are living here in the city. I go out on the street and encounter human suffering, and I offer what I can. That’s my life—there’s no getting around it, even if I wanted to. But if you walk out of a monastery gate and confront an ecological problem, then you’re likely to respond to that.

But there are a lot of exhortations, for example, from the Zen classics, to go up to the mountain. It wasn’t “go up to the mountain and plant trees,” it was “go up to the mountain and get yourself out of this secular misery.” Yes, of course, it is necessary to retreat. But one can retreat wherever one is. It is not about a mountain, it is about attachment to the affairs of the world. But you’re right. There was a tendency to withdraw, and that’s what we do when we meditate: we withdraw for a bit of time, we let go of our attachments. But we don’t stay there: we go outside, and there’s someone who needs the simple respect of eye contact, or a smile, or a buck for a cup of coffee. Much of Zen literature is also about the need to go back down the mountain to the marketplace. This is the mark of true realization in Zen. I really try to emphasize here that we don’t walk out the door in some kind of bliss state where we’re not able to see the suffering that’s going on or the horror of the traffic or of the runaway consumption of resources. It’s about doing what you can, where you are, with what’s right in front of you, right now.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.