Tibetan Buddhist monk Konchog Tendzin was born Matthieu Ricard in Aix-les-Bains, France, in 1946. As a young man he trained as a classical harpsichordist and pursued interests in wildlife photography, astronomy, and animal migration. At 26 he earned a Ph.D. in molecular biology. His interest in Tibetan Buddhism began in 1967, when his friend the French filmmaker Arnaud Desjardins made a film about Himalayan Buddhist masters for French television.

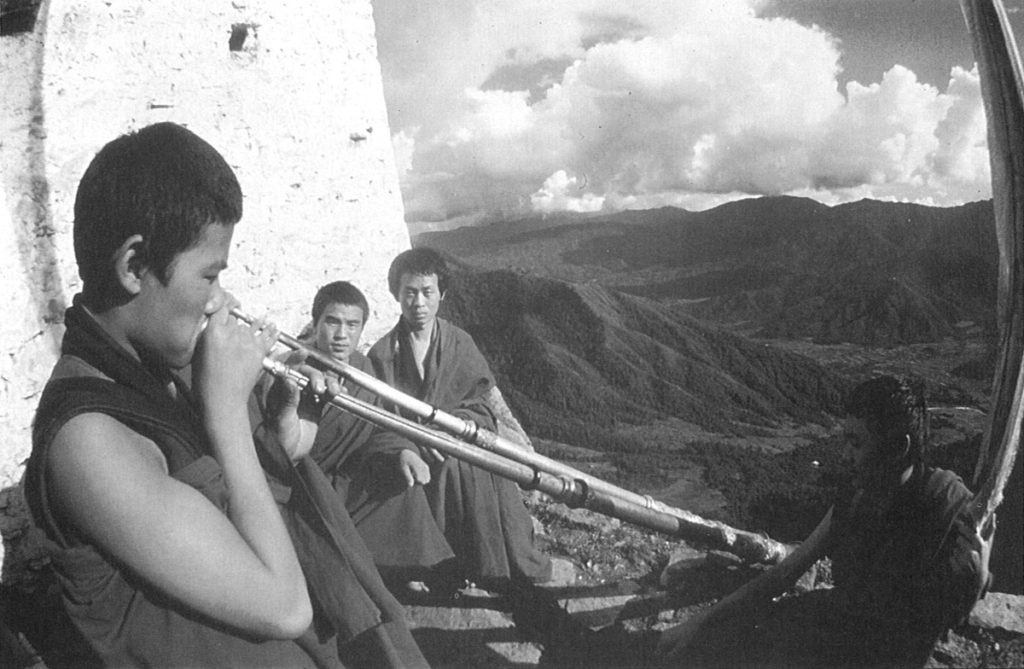

Konchog Tendzin trained in the Nyingmapa School of Tibetan Buddhism and was a close student of Kangyur Rinpoche and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche until the end of their lives. Ordained as a monk in 1979, he has lived in the Himalayas ever since. He has served as a translator for many Tibetan Buddhist teachers, including His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and has translated such works as The Life of Shabkar (SUNY Press) and The Heart Treasure of the Enlightened Ones (Shambhala). He now lives at Shechen Monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal. This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Senior Editor Clark Strand in New York, May 1995.

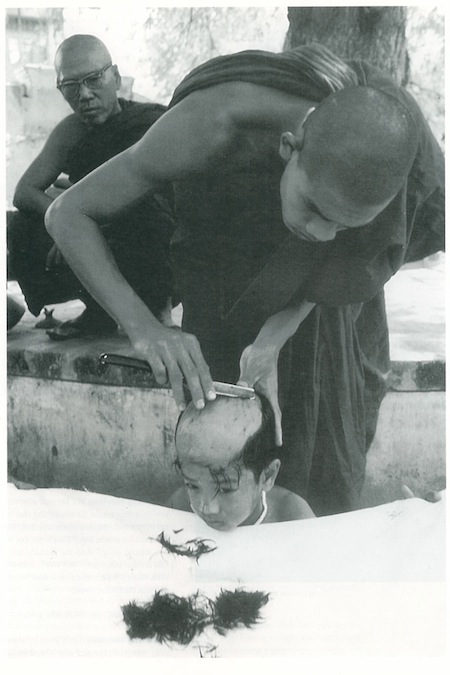

When did you become a monk? When I was thirty. Some years before, I had asked my root teacher, Kangyur Rinpoche, whether I should become a monk. He said, “Don’t hurry. Until you are thirty, just practice and things will become clear. Until then, simply don’t get married.” When I turned thirty, Kangyur Rinpoche was no longer alive. I was with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. At that time a very great abbot of the Nyingmapa order came to the place where we were, and he was going to give vows to many postulants. So I turned to Khyentse Rinpoche and asked, “What should I do? I’m open to whatever you say.” He said, “It’s a very good opportunity to take vows with this very pure lineage.” So, I took vows.

How many vows were there? There are 253 vows.

That’s a lot to remember. It seems daunting. But, in fact, they’re all very natural. The moment you feel yourself as a renunciate—as a monk—they’re obvious. For instance, the vow not to kill any kind of living being—especially a human being, or a human being in the process of formation. Also, there’s the vow not to take what is not given. And the vow of celibacy, and not to boast about spiritual attainments. Breaking one of these major vows causes you immediately to lose your ordination, which means that you are no longer a monk. And there are thirteen others, called “remnants.” Breaking one of these is very damaging, but the damage can be repaired.

What are some of those? Well, they are mostly branches of the first ones, rules governing stealing, chastity, and so forth.

What are the vows you find most difficult to keep? They’re not really so difficult. At the time you take vows, you should not feel that you are getting into a system that is binding you. If you think that becoming a monk is some kind of withdrawal, a sort of asceticism in the terms of forcing yourself to do certain things, and not to do others, then that is a problem. The aim of renunciation is freedom. That was the experience I had when I took vows—this incredible feeling of freedom. It felt like a bird suddenly took off in the sky, like being released from all bounds. I think that’s the only way you can remain a monk, if you enjoy that sort of feeling.

Many who took monastic vows in the seventies and eighties have left the monkhood for one reason or another. I think that’s because they probably didn’t feel that kind of freedom. A sort of steam builds up. Then, suddenly, it blows. If there’s that kind of hindrance, it’s better not to become a monk.

How do you account for the difference? You speak of the monkhood as if it were an experience of great freedom and openness. But for most people the thought of making 253 vows sounds very constricting. I know. But most of them are just common sense. For instance, one of them is not to eat after lunch. That’s very good for your health, and it gives you more time to study and practice. And there are rules about monastic robes that remind you to be mindful. There are rules about certain things, like cutting down trees or plowing fields, because you kill by doing so. There’s nothing that seems completely weird.

If you use a plow, then there’s the feeling that maybe you might slice a worm in half. Is that the idea? It’s not just a feeling. You will certainly kill hundreds of worms. But that’s just an example. From a Buddhist point of view, the vows are all just obvious things to do in order to progress on the path.

I was told a story years ago by my own teacher. He talked about traveling to a temple in Thailand where the monks were very strict. He told the story of how one Thai monk constantly corrected his behavior. The monk insisted that he place his robe in a certain way because the Buddha had said so, and that he bow a certain way because the Buddha had said that, too. But when my teacher went into temple, he found that many of the monks were smoking. When he asked about this, the monk replied that the Buddha never said not to smoke. Well, of course, that is true. In the beginning, there were no specific rules for monks. The Buddha just ordained them. That was it.

But then the Buddha made rules. Yes, because after some years a monk would do something that was not in line with the ideal of a renunciate. Then the Buddha would say, “That’s not the way you should do it.” And the Buddha would rule on that behavior. Every rule is based on such stories. It happened each time because of some particular event.

Even after the Buddha’s death? The Vinaya [monastic rule] was not a changed after the Buddha’s death. There were different interpretations by the eighteen Buddhist schools that evolved later on, but they were relatively minor. The major vows are all the same. So we would think it’s obvious for a monk not to smoke, but since the Buddha didn’t rule on it, it’s a matter of interpretation.

The Buddha didn’t say anything about crack addiction either. Right. But there are other admonitions—for instance, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition—explaining very specifically that tobacco and all other intoxicants are major hindrances to progress on the spiritual path. So Theravada or Hinayana Buddhism is not really the “lesser vehicle.” Tibetan Buddhists consider it the foundation. The ground floor is just as important as what’s above. The Tibetan Buddhist integrates Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana, and one practitioner practices all three at the same time.

Buddhist monks in America—especially, say, in the Zen tradition—are sometimes disparagingly referred to as “weekend monastics,” because they have families, and sometimes jobs—because they may have any number of other commitments in addition to being a monk. When I hear you talk about giving up all distractions and feeling free just to practice, I wonder what you think of that kind of monastic practice. Is it monasticism at all? Well, let’s just say it’s best to stop having worldly preoccupations when you become a monk.

But plenty of people want the benefits of monastic practice. And yet they may not feel ready to commit to monasticism. Is there some middle ground? It all depends on how much determination you have. If your determination is fifty-fifty, then of course you are not fully committed. Actually, if you are really practicing all the time, then it makes no difference whether you are monk or not. Being a monk is just a way of helping you do that. You make a commitment, and you stick to it. You don’t change your mind every two or three days.

Who ordained the Buddha? Was the Buddha a monk? Well, you know, at the time of the Buddha, there were many ways to become a monk. The first was to become a buddha. By becoming enlightened you’re a natural bhikkhu [monk]. And, of course, at the time of the Buddha there was no ordination ritual. The Buddha just said, “Come to me.” That was the ordination.

“Come to me”? Yes. “Come to me.” When the Buddha said that to somebody, instantly they became a bhikkhu. And there were other ways as well. But now it’s only the last way, ritual ordination, that’s extant. Except of course that even now someone who becomes fully enlightened becomes a natural bhikkhu, like the Buddha. This is clearly mentioned in the Vinaya: the Buddha became a bhikkhu by attaining enlightenment.

When we say that the monastic community is the foundation of the Buddha-dharma, and if the Vinaya teaching were to disappear, Buddha-dharma would collapse, it doesn’t mean again that monastic discipline is the essence, the highest teaching and so forth. It means that it is the foundation. Even when you’re living in a beautiful palace, you still need a foundation.

Do you think that real Buddhism can develop fully in the West without that monastic foundation? I think that gradually people will come to realize how hard it is to pass from a sincere and strong interest in Buddhism into a complete way of life. Take the example of the Tibetan community. Most Tibetan laypeople have a very sincere, day-to-day, moment-to-moment sort of feeling toward the dharma. But they don’t pose as great practitioners. They don’t pose as teachers. They just think that somehow, due to karmic conditions, they have to remain in the worldly life. But they’re very aware that if they really wanted to practice the dharma more seriously, they would give up worldly concerns. And many of them do, at some point in their lives.

So, if there are enough people like that— Then out of them a certain percentage will try to remember the dharma all day long, throughout all their activities. If that happens in large numbers, then naturally out of those people there’ll be some who decide, “Now I will only practice, and be happy doing that.” And that will be the beginning of a stable monastic community. And out of those communities, again, there will be some outstanding practitioners who will eventually become genuine teachers. When you want to make a football team, you start with one thousand kids, and maybe twelve of them will become really good. It has to be like that. You can’t just start from nothing.

Certainly, in this country there’s the feeling in some communities that the monks and nuns are somehow the elite, the professional Buddhists, so to speak. As Buddhism becomes more and more popular—and secular—being a monk takes on a certain cache, a sort of glamour one hardly sees when one looks at Trappist monks, for instance, for whom being Christian is quite ordinary. In that tradition, a monk lives and practices, often for his entire life, behind cloistered walls without ever coming out, and seldom if ever achieving any worldly fame or recognition. That’s what a monk should be. I don’t mean doing a lifelong retreat—though that’s wonderful if they can do it—but being humble. Certainly that’s the way a monk should be. Humility is the basic quality of a monk. You should be like water and always take the lowest possible level. Without humility, the whole thing gets screwed up.

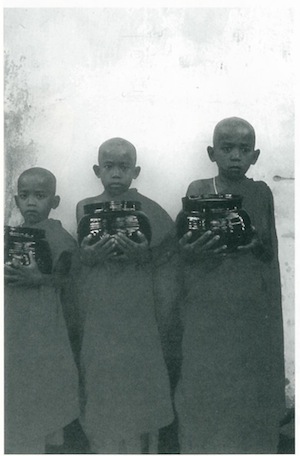

What do you think will happen to Tibetan Buddhism and its monastic traditions? What happens when you take monasticism out of the context of its centuries-old tradition in Tibet and put it, for instance, in India or southern France. I don’t know about southern France, but in India certainly it is thriving, at least in the sense that there’s no crisis of monastic vocations. At Shechen Monastery in Nepal, we have 170 monks, but we could double that number every six months if we simply had the place to put them and the food to give them. Almost every week we refuse two or three persons who say they want to join. They have to wait until someone goes to another monastery.

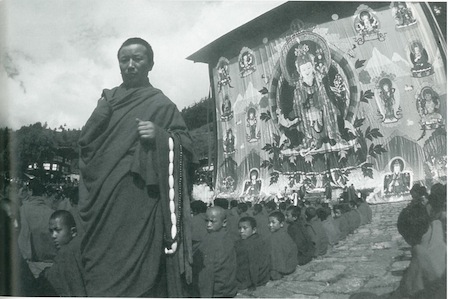

Earlier you mentioned the rules governing monastic dress. I think that people tend to think that monastic dress is of no importance. Maybe it’s a minor point, but my teacher Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche didn’t appreciate the idea that a monk might be able to mingle better with society in laymen’s clothes.

Why was that? He said, “Well, first you take off your shawl. Then, you eventually go in pants. Finally you lose your vows.” That seems to be an almost natural progression. Because monastic dress is a constant reminder to practice vigilance and self-discipline. That’s why, for instance, they say you’re never supposed to spend a night away from your formal outer robe. You should at least be back with it when the sun rises. So that’s an aid to vigilance. If the monks were just walking off without their robes, they might be tempted to sleep somewhere else, and all sorts of things might happen. So, all these rules are like helpers.—[Pointing to a balcony in the apartment where he is staying]—What do you call this thing you have around the balcony? I don’t know the English.

The rail. Yes, the rail, so as not to fall down. The vows are like rails. They’re not just a lot of silly rules made up in order to restrict your way of life. They make sense. If you are dressed as a layman you might say, “Okay, let’s go to the disco. It’s not that bad, after all. If you have the right inward motivation, it’s okay.” That’s how you begin to go adrift. So it helps you to maintain certain rules of outward conduct—because that’s what the Vinaya actually is—a guide to outer conduct. The Bodhisattava vows are for the inner motivation.

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche use to that the best formula for a monk was to follow the outward model of Theravada Buddhism, inwardly to have the altruistic motivation of a bodhisattva, and secretly to practice the teachings of the Vajrayana. That way all three vehicles become a single path.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.