LIKE EVERYTHING the British poet Edwin Arnold wrote, The Light of Asia was quickly written: a poem in eight books of about five hundred lines each, mostly in blank verse, composed over a period of several months when Arnold was busy with other concerns. Immediately upon its publication in the summer of 1879, the poem began to sell copies and win attention. It was a life of Siddhartha Gautama, told from the point of view of “an Indian Buddhist” (so read the title page) in high English style. The immediate sensation surrounding The Light of Asia was remarkable: for some time on both sides of the Atlantic, newspapers and dining rooms were charged with discussion about the Buddha, his teaching, and Arnold’s presentation of Buddhism. The book’s success was also sustained. By 1885 the authorized English version had gone through thirty editions. Pirated editions, which went for as little as three cents in the U.S., make a count of the book’s circulation impossible, but it has been estimated at a million copies (not far short of Huckleberry Finn). After thirty years it had become one of the undisputed bestsellers of Victorian England and America, had been translated into a number of languages (German, Dutch, French, Czech, Italian, Swedish, Esperanto), and had inspired a stage version and even an opera.

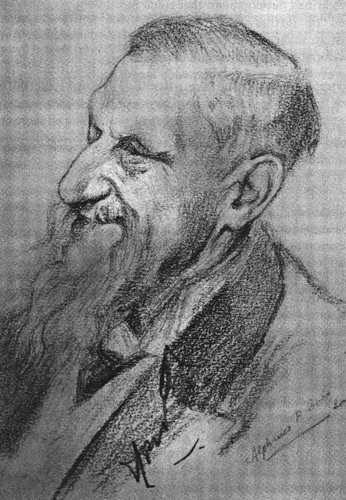

Edwin Arnold was born in 1832 at Gravesend, a Thames port town near London. The man who was to become the first well-known popularizer of Buddhism in England and America grew up in an established English family. He attended school in London and then went to Oxford, where he won the Newdigate Prize, a sought-after poetry award, for an Orientalist prophecy called The Feast of Belshazzar. Benjamin Disraeli, a novelist soon to make his mark as a politician, acclaimed Arnold on the occasion and predicted he would have a brilliant future. From a young age, Arnold typified the hardworking, successful Victorian gentleman.

After working as a schoolmaster in Birmingham, the young Arnold went abroad to India, where he served as principal of a school at Poona. It is impossible to know how much Arnold learned about Indian civilization in his four years there while he managed the school and gave lectures on Western science and literature. But it does seem that Arnold’s Western literary vision of an exotic Orient—an Orient of gold, gems, strange scents, and mysterious wisdom—was moderated and humanized by his experiences.

Arnold returned from India a confirmed internationalist, and became first a writer and then an editor at The Daily Telegraph in London. (The paper was the first penny daily and one of the most prominent public voices of the Empire.) Soon Arnold became known for his poetry and journalism as well as his essays and translations from French, Greek, and Sanskrit. But it was in 1879 that Arnold achieved real fame with the publication ofThe Light of Asia.

How did The Light of Asia achieve such popularity? Some of its success might be ascribed to Arnold’s position at the center of the English literary world and simply to good timing. In 1879, East Asian affairs were claiming much attention and curiosity, and English and American readers were eager to hear about Buddhism. With its overtly moral, international interest, The Light of Asia occasioned debate over some of the most controversial and vexing issues of the day, questions about religion, cultural difference, morality, and dogma. To Arnold’s readers the story of the Buddha was reassuring. New theories of geological time and evolution, and new modes of historical criticism, had shaken Christian orthodoxy. At the same time, since Western scholars had begun learning about Buddhism at the beginning of the century, the Buddha had come to be regarded as an exemplary moral figure. Popular curiosity about Buddhism was partly due to the challenge it posed to Christianity. Yet it was also an expression of the public’s desire to see “Christian virtues” confirmed.

More simply, many considered The Light of Asia a splendid poem, “a work of great beauty” with “a story of intense interest, which never flags for a moment,” according to Oliver Wendell Holmes. By half claiming to present an authentic teaching of the East, it stirred the inquisitive, self-confident Victorian imagination; but the poem was popular in part because it was so familiar. The reading public had long cultivated a taste for the exotic, and the lavish and picturesque Indian world of Arnold’s poem was not very unlike what it knew from the same Orientalist romances Arnold had grown up with. The poem is extremely literary: it was not hard to note, among Arnold’s epic lists and similes and long dialogues, echoes of Shakespeare, Milton, Keats, and others. Arnold also gave his subject a deliberate nobility—ancient Kapilavastu is sensual but not barbaric—and this, too, appealed to the Victorian reader. The Buddha is frankly portrayed as a saint or holy man. Episodes about Siddhartha even before his enlightenment echo biblical stories of good deeds or miracles. Arnold was able all at once to present the life of Siddhartha with great sympathy, to satisfy his readers’ tastes, and to allay their anxieties.

Thus many Americans were first inspired to a favorable regard of the Buddha by the poem of an Englishman. If there was irony in this it may also be possible to view it as the operation of historical good fortune, a kind of impersonal skillful means. Despite their curiosity, English and American readers in 1879 were not ready to entertain seriously a doctrine that came in a garb so outlandish, to them, as that a living Buddhism would have worn. In Arnold’s epic hero they were introduced to a Buddha they might have called their own.

The Light of Asia (from Book 7)

When Book 7 begins, the Buddha has achieved enlightenment. At Kapilavastu, the king Suddhodana and Yasodhara, the wife of Siddhartha, still mourn his loss. Yasodhara hears rumors that the prophecy has been fulfilled and that Siddhartha has become a holy man. She rejoices and calls for the merchants who have spoken of him, and they come and report that they have seen him. A merchant tells of how he was enlightened sitting under the Bodhi tree, how he resolved to proclaim what he had seen, how he started teaching, and how he has been acclaimed by King Bimbasara. King Suddhodana and Yasodhara both send out messengers, but they, coming to where the Buddha teaches in the bamboo grove, Join the community of his disciples. Suddhodana then sends Udayi, the friend of Siddhartha’s youth. He goes to the Buddha, who answers that he will come to the city. Kapilavastu prepares itself to receive the prince. Yasodhara rides to the gate to meet him. Going out she meets a hermit surrounded by followers, who proves to be Siddhartha. She falls at his feet. Book 7 then turns to the king.

But when the King heard how Sidhartha came

Shorn, with the mendicant’s sad-coloured cloth,

And stretching out a bowl to gather orts

From base-borns’ leavings, wrathful sorrow drave

Love from his heart. Thrice on the ground he spat,

Plucked at his silvered beard, and strode straight forth

Lackeyed by trembling lords. Frowning he clomb

Upon his war-horse, drove the spurs, and dashed,

Angered through wandering streets and lanes of folk

Scarce finding breath to say, “The King, bow down!”

Ere the loud cavalcade had clattered by:

Which—at the turning by the Temple-wall,

Where the south gate was seen—encountered full

A mighty crowd; to every edge of it

Poured fast more people, till the roads were lost,

Blotted by that huge company which thronged

And grew, close following him whose look serene

Met the old King’s. Not lived the father’s wrath

Longer than while the gentle eyes of Buddh

Lingered in worship on his troubled brows,

Then downcast sank, with his true knee, to earth

In proud humility. So dear it seemed

To see the Prince, to know him whole, to mark

That glory greater than of earthly state

Crowning his head, that majesty which brought

All men, so awed and silent, in his steps.

Nathless, the King broke forth, “Ends it in this

That great Sidhartha steals into his realm,

Wrapt in a clout, shorn, sandalled, craving food

Of low-borns, he whose life was as a god’s?

My son! heir of this spacious power, and heir

Of Kings who did but clap their palms to have

What earth could give or eager service bring?

Thou should’st have come apparelled in thy rank,

With shining spears, and tramp of horse and foot.

Lo! all my soldiers camped upon the road,

And all my city waited at the gates;

Where hast thou sojourned through these evil years

Whilst thy crowned father mourned? and she, too,

there

Lived as the widows used, foregoing joys;

Never once hearing sound of song or string,

Nor wearing once the festal robe, till now

When in her cloth of gold she welcomes home

A beggar-spouse in yellow remnants clad.

Son! why is this?”

“My father!” came reply,

“It is the custom of my race.”

“Thy race,”

Answered the King, “counteth a hundred thrones

From Maha Sammat, but no deed like this.”

“Not of a mortal line,” the Master said,

“I spake, but of descent invisible,

The Buddhas who have been and who shall be

Of these am I, and what they did I do.

And this, which now befalls, so fell before,

That at his gate a King in warrior-mail

Should meet his son, a Prince in hermit-weeds;

And that, by love and self-control, being more

Than mightiest Kings in all their puissance,

The appointed helper of the Worlds should bow—

As now do I—and with all lowly love

Proffer, where it is owed for tender debts,

The first-fruits of the treasure he hath brought; Which I now proffer.”

Then the King amazed

Inquired “What treasure?” and the Teacher took

Meekly the royal palm, and while they paced

Through worshiping streets—the Princess

and the King

On either side—he told the things which make

For peace and pureness, those Four Noble Truths

Which hold all wisdom as shores shut the seas,

Those eight right Rules whereby who will may walk—

Monarch or slave-upon the perfect Path

That hath its Stages Four and Precepts Eight,

Whereby whoso will live—mighty or mean,

Wise or unlearned, man, woman, young or old—

Shall, soon or late, break from the wheels of life,

Attaining blest Nirvana. So they came

Into the Palace-porch, Suddhodana

With brows unknit drinking the mighty words,

And in his own hand carrying Buddha’s bowl,

Whilst a new light brightened the lovely eyes

Of sweet Yasodhara and sunned her tears;

And that night entered they the Way of Peace.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.