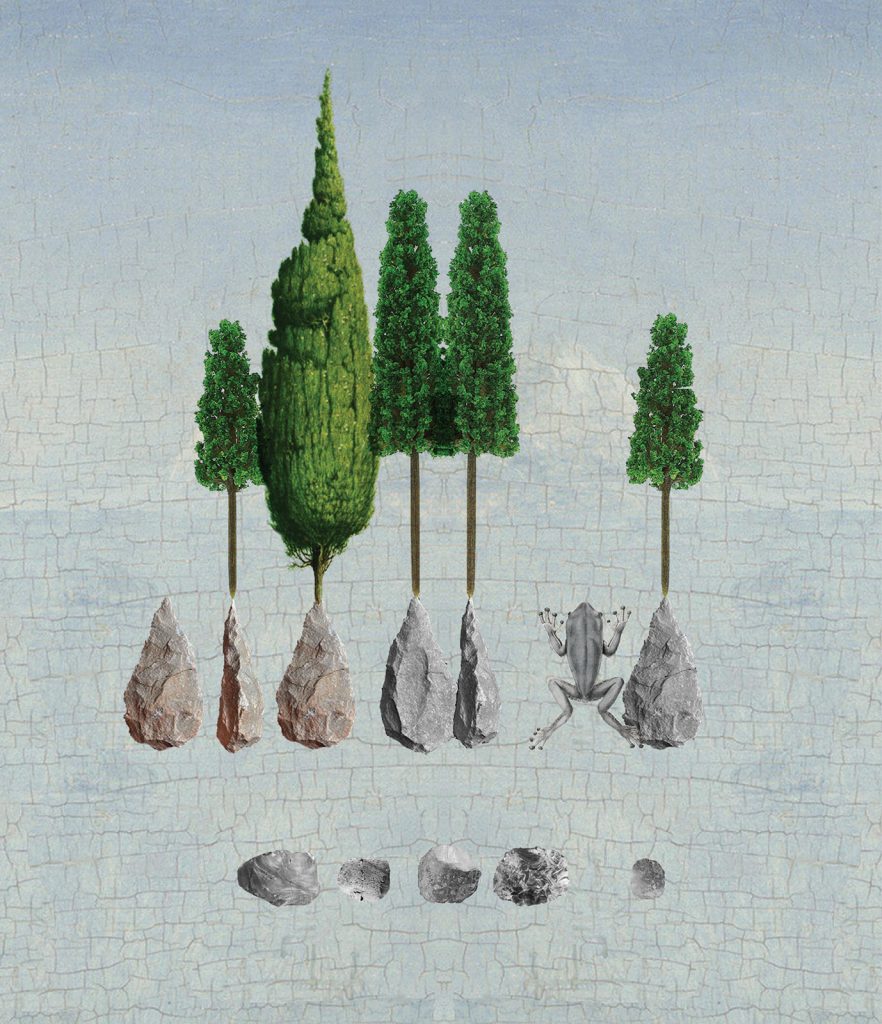

the easing of grief

a stone beneath the cypress

becomes a small frog

— Lynne Rees

As a body of literature, English-language haiku has rarely produced poems with the mythic depth or historical resonance that one expects from the best Western poetry. This will change as our poets learn to use the techniques of Japanese haiku to explore the symbols that inform their own cultural experience.

Cypresses have long been associated with mourning. The Orphic gold tablets found in Greek graves describe a white cypress near the entrance to the underworld. In ancient Rome cypress branches were hung on the doors of homes in mourning. Even today, cupressus sempervirens is the most common tree in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim cemeteries.

The poet can leave a lot unsaid because of these associations. She doesn’t have to describe the graveyard, for instance. The words grief, stone, and cypress establish the scene. The light beneath the tree is dim, the space liminal. The stage is set for a magic that only nature can perform.

The transformation of an inanimate object into an animal is one of the oldest tricks in haiku. The most famous example is by Arakida Moritake (1473–1549), a poet who became the head priest of the Inner Shrine at Ise:

A fallen blossom

returned to the branch?

But no…it’s a butterfly!

The poem relies upon a misperception, which is corrected in a delightful way. What is the message? The line separating the living from the dead is largely a matter of perspective.

There is none of Moritake’s lightheartedness in Rees’s haiku (inspired by the season word frog). But the corrected perception is still there. Lost in mourning, she finds a place to rest her eyes in the gloom of the cypress shade. A small stone at her foot seems to express the intractable immobility of her sorrow. Then it moves . . . and her grief moves with it.

It is important to note that the poet’s grief has not been erased . . . only eased. The humor of the poem (and there is humor in every good haiku, however dark or uncanny) lies in the fact that a little frog performs this act of redemption, rather than something grander.

It doesn’t take much to show us that the world is constantly renewing itself, provided we are attentive to the cycles of nature. Nothing is fixed. Nothing is stuck. When something is lost, something is always given.

It’s not over until it’s over—and it’s never over. This is the wisdom of haiku.

♦

The Tricycle Haiku Challenge asks readers to submit original works inspired by a season word. Moderator Clark Strand selects the top poems to be published in Tricycle with his commentary. To see past winners and submit your haiku, visit tricycle.org/haiku.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.