The pneumatic mattress massaged her skin; there were pads between her knees, and they had a hoop over them to prevent the sheets from touching; another arrangement stopped her heels touching the draw-sheet: but for all that, bedsores were beginning to appear all over her body. With her hips paralyzed by arthritis, her right arm half powerless and left immovably fixed to the intravenous dripper, she could not make the first beginnings of a movement.

“Pull me up,” she said.

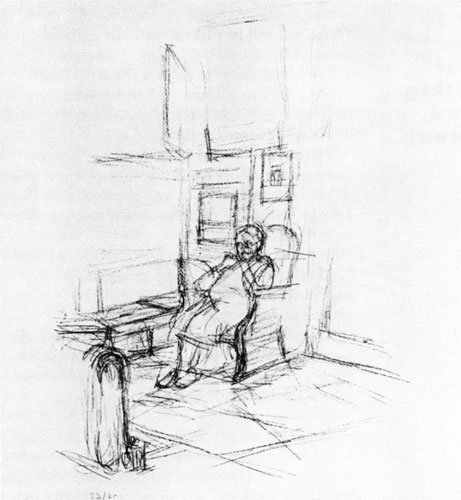

I dared not, all by myself. I was not worried by her nakedness any more: it was no longer my mother, but a poor tormented body. Yet I was frightened by the horrible mystery that I sensed, without in any way visualizing anything, under the dressings, and I was afraid of hurting her. That morning she had had to have another enema and Mademoiselle Leblon had needed my help. I took hold of that skeleton clothed in damp blue skin, holding under the armpits. When Maman was laid over on her side, her face screwed up, her eyes turned back and she cried, “I am going to fall.” She was remembering the time she had fallen down. Standing by the side of her bed I held her and comforted her.

We sat her up again, carefully propped with pillows. After a moment she exclaimed, “I have broken wind!” A little later she cried, “Quick, the bedpan.” Mademoiselle Leblon and a red-haired nurse tried to put her on to a bedpan; she cried out; seeing her raw flesh and the harsh gleam of the metal, I had the impression that they were setting her down on knife-edges. The two women urged her, pulled her about, and the red-haired nurse was rough with her; Maman cried out, her body tense with pain. “Ah! Leave her alone!” I said.

I went out with the nurses. “It doesn’t matter. Let her do it in her bed.”

“But it is so humiliating,” protested Mademoiselle Leblon. “Patients cannot bear it.”

“And she will be soaked,” said the redhead. “It is very bad for her bedsores. “

“You can change the clothes at once,” I said.

I went back to Maman. “That red-haired one is an evil woman,” she moaned in her little girl’s voice. And much distressed she added, “Still, I didn’t think I was a crybaby.”

“You aren’t one.” And I said to her, “You don’t have to bother about a bedpan. They will change the sheets—there’s no sort of difficulty about it.”

“Yes,” she replied. And with a frown and a look of determination on her face she said, as though she were uttering a challenge, “The dead certainly do it in their beds.”

This took me completely aback. “It is so humiliating.” And Maman, who had lived a life bristling with proud sensitivities, felt no shame. In this prim and spiritualistic woman it was also a form of courage to take on our animality with so much decision.

She was changed, cleaned, and rubbed with alcohol. Now it was time for her to have a quite painful injection that was meant, I think, to counteract the urea, which she was not getting rid of properly. She seemed so exhausted that Mademoiselle Leblon hesitated. “Do it,” said Maman, “since it’s good for me.”

Once more we turned her over on to her side; I held her and I watched her face, which showed a mixture of confused distress, courage, hope, and anguish. “Since it is good for me.” In order to get well. In order to die. I should have liked to beg someone to forgive me.

The next day I learned that the afternoon had passed off well. A young male nurse had taken Mademoiselle Leblon’s place and Poupette said to Maman, “How lucky you are to have such a young, kind nurse.”

“Yes,” said Maman, “he’s such a good-looking fellow.”

“And you are a judge of men!”

“Oh, not much of a judge,” said Maman, with nostalgia in her voice.

“You have regrets?”

Maman laughed and said, “I always say to my grandnieces, ‘My dears, make the most of your life.'”

“Now I understand why they love you so much. But you would never have said that to your daughters?”

“To my daughters?” said Maman, with sudden severity. “Certainly not!”

Dr. P. had brought her an eighty-year-old woman on whom he was to operate the next day and who was frightened: Maman lectured her, setting forth her own case as an example.

“They are using me as an advertisement,” she told me in an amused voice on Monday. She asked me, “Has my right side come back? I really do have a right side?”

“Of course you have. Look at yourself,” said my sister.

Maman fixed an unbelieving, severe, and haughty gaze upon the mirror. “Is that me?”

“Why, yes. You can see that all your face is there.”

“It is quite gray.”

“That’s the light. You are really pink.”

She did in fact look very well. Nevertheless, when she smiled at Mademoiselle Leblon she said to her, “Ah! This time I smiled at you with the whole of my mouth. Before, I only had half a smile.”

In the afternoon she was not smiling anymore. Several times she repeated, in a surprised and blaming voice, “When I saw myself in the mirror I thought I was so ugly!”

The night before, something had gone quite wrong with the intravenous drip: the tube had had to be taken out and then thrust back into the vein.

The night nurse had fumbled, the liquid had flowed under the skin and it had hurt Maman very much. Her blue and hugely swollen arm was swathed in bandages. The apparatus was not attached to her right arm: her tired veins could just put up with the serum, but the plasma forced groans from her. In the evening an intense anxiety came over her: she was afraid of the night, of some fresh accident, of pain. With her face all tense she begged, “Watch over the drip very carefully!” And that evening too, as I looked at her arm, into which there was flowing a life that was no longer anything but sickness and torment, I asked myself why.

At the nursing home I did not have time to go into it. I had to help Maman to spit; I had to give her something to drink, arrange her pillows or her plait, move her leg, water her flowers, open the window, close it, read her the paper, answer her questions, wind up the watch that laid on her chest, hanging from a black ribbon. She took a pleasure in her dependence and she called out for our attention all the time. But when I reached home, all the sadness and horror of these last days dropped upon me with all its weight. And I too had a cancer eating into me—remorse. “Don’t let them operate on her.” And I had not prevented anything.

Often, hearing of sick people undergoing a long martyrdom, I had felt indignant at the apathy of their relatives. “For my part, I should kill him.” At the first trial I had given in: beaten by the ethics of society, I had abjured my own. “No,” Sartre said to me. “You were beaten by technique: and that was fatal.” Indeed it was. One is caught up in the wheels and dragged along, powerless in the face of specialists’ diagnoses, their forecasts, their decisions. The patient becomes their property: get him away from them if you can! There were only two things to choose between on that Wednesday—operating or euthanasia. Maman, vigorously resuscitated, and having a strong heart, would have stood out against the intestinal stoppage for a long while and she would have lived through hell, for the doctors would have refused euthanasia. I ought to have been there at six in the morning. But even so, would I have dared to say to N., “Let her go”? That was what I was suggesting when I begged, “Do not torment her,” and he had snubbed me with all the arrogance of a man who is certain of his duty. They would have said to me, “You may be depriving her of several years of life.” And I was forced to yield.

These arguments did not bring me peace. The future horrified me. When I was fifteen my uncle Maurice died of cancer of the stomach. I was told that for days on end he shrieked, “Finish me off. Give me my revolver. Have pity on me.” Would Dr. P. keep his promise: “She shall not suffer”? A race had begun between death and torture. I asked myself how one manages to go on living when someone you love has called out to you, “Have pity on me” in vain.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.