River-Horse: The Logbook of a Boat Across America

William Least Heat-Moon

Penguin, 2001

506 pp., $14 paper

A River Sutra

Gita Mehta

Vintage, 1994

291 pp., $14.95 paper

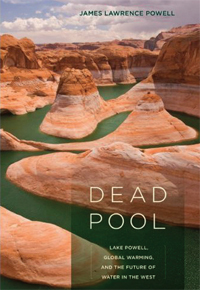

Dead Pool: Lake Powell, Global Warming, and the Future of Water in the West

James Lawrence Powell

University of California Press, 2008

304 pp., $27.50 cloth

A book, a boat; I am still grasping its scope, a journey in the mid-1990s from New York City five thousand miles to the Pacific—inland. A voyage through the land—it sounds metaphorical but is endlessly particular, this month-by-month navigating of unpredictable waterways in a twenty-two-by-eight-foot cross between a lobster dory and an old-fashioned harbor tug, its Osage name Nikawa, which is “River-Horse” in English, given by its Native American designer, skipper, compendious thinker, and writer, William Least Heat-Moon. Recommended by a fellow novelist who knew I was writing, this time, a nonfiction book about water, “River-Horse” came into my life when I was in the middle of reading other books (such as the two listed above, a novel about a sacred Indian river and a scientist’s account of the future of the great American desert). What is it to read several books at a time? I felt a curious permission, hearing about all those books in Nikawa’s forward cabin for which the skipper finds time while fixing battered propellers, reading treacherous currents and shallows, dodging flood-borne debris, even uprooted trees coming at you like land adrift. To say nothing of chances, week after week, that you and your variable one- or two-man crew won’t make it and will have to give up. Yet this northern coast-to-coast route, crucially including the Missouri, constantly reminds us of other closer, companionable and mysterious coasts of riverbank people, their 24/7 lives a continent of voices to stop and share experience with.

A book, a boat; I am still grasping its scope, a journey in the mid-1990s from New York City five thousand miles to the Pacific—inland. A voyage through the land—it sounds metaphorical but is endlessly particular, this month-by-month navigating of unpredictable waterways in a twenty-two-by-eight-foot cross between a lobster dory and an old-fashioned harbor tug, its Osage name Nikawa, which is “River-Horse” in English, given by its Native American designer, skipper, compendious thinker, and writer, William Least Heat-Moon. Recommended by a fellow novelist who knew I was writing, this time, a nonfiction book about water, “River-Horse” came into my life when I was in the middle of reading other books (such as the two listed above, a novel about a sacred Indian river and a scientist’s account of the future of the great American desert). What is it to read several books at a time? I felt a curious permission, hearing about all those books in Nikawa’s forward cabin for which the skipper finds time while fixing battered propellers, reading treacherous currents and shallows, dodging flood-borne debris, even uprooted trees coming at you like land adrift. To say nothing of chances, week after week, that you and your variable one- or two-man crew won’t make it and will have to give up. Yet this northern coast-to-coast route, crucially including the Missouri, constantly reminds us of other closer, companionable and mysterious coasts of riverbank people, their 24/7 lives a continent of voices to stop and share experience with.

Rivers, as Pascal says, are moving roads that take you where you want to go (which means you are willing to be taken). This book reminds me I might not want to rush through it, but stay with it for weeks, rereading, meditating on its passages which will be a little different the next time. Like the maps that are for Heat-Moon “holy writ,” his karmic space holds much of our own experience that comes to mind like threads that hold us together. Even as the world comes to you sometimes when you would turn away from it: one meaning, in fact, of Gita Mehta’s “A River Sutra,” where a retired civil servant, now custodian of a remote “rest house” on the banks of the Narmada, finds lives of others finding him, stories neighboring or inspired by an ancient river, stories within stories like an extended family. Parents seeking lost children, a daughter learning music from a difficult and famous father who calls a raga a riverbed, its grace notes the water, while elsewhere we are the “water washing over stone.” Ascetic ordeals, river minstrels, a descant or debate all through this novel asks if this river that reputedly contains four hundred billion sacred places is woman, god, medicine, window, holy release from the birth and death cycle, an ecology of the interdependence of all life—or, as one character, a secular archaeologist, sees it, “the individual experiences of those who have lived here.”

Time narrows choices to emergencies and if water’s various imaginings drew me into it, so did the exact analysis that is another form of story and as intense and attentive to event as any breathless page-turner. Such is James Lawrence Powell’s “Dead Pool,” about the mismanagement of the Colorado River and Lake Powell, flood and drought, dams and silt, oncoming disaster. Ultimately it was lack of imagination in meeting successive emergencies decade after decade, and a politics weirdly not only of greed, that helps me ask how all our individual experiences may find a communal intelligence of survival. Asks also, survival of what?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.