THE WHEEL OF TIME SAND MANDALA: Visual Scripture of Tibetan Buddhism

Barry Bryant

HarperSanFrancisco: San Francisco, 1993.

256 pp., $35.00 (hardback).

Deborah Sommer

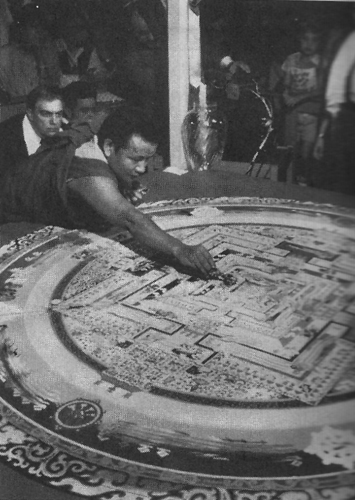

TIBETAN SAND MANDALAS from the roof of the world have weathered the descent into the American spiritual consciousness with remarkable aplomb. In their homeland, they were shielded from both profane admiration and the vicissitudes of temporal existenceeach one was purposefully dismantled at the end of its brieflife span of a few days or weeks. Their karmic fate took a new turn, however, as the esoterica of Tibet were reborn in the lower climes of the Western Hemisphere, where they encountered the exoteric media of the modern age. Publicly exhibited in museums and galleries on both coasts, relentlessly photographed and videotaped, and astutely marketed as posters, note cards, calendars, and book totes, these pliant expressions of pristine consciousness have over the past decade survived gross transmutations of shape and form with their voidness gracefully intact. Reincarnation in America’s own special brand of samsaric existence has not been without its highs and lows, as the art of the mandala has survived three-dimensional vertical expansion by computer-imaging systems and suffered horizontal demolition by the flailing body of a deranged Californian observer who experienced the mandala as the product of a death cult.

As these visual images have accommodated themselves so willingly to translation into various Western media, one might suppose they would have generated a substantial literature as well. Yet the relationship between image and word is a delicate one: viewing a mandala is one thing; describing it is quite another; and explaining it in its historical, philosophical, and ritual context is something else again. Barry Bryant’sThe Wheel of Time Sand Mandala: Visual Scripture of Tibetan Buddhism is one of the few books accessible to a general readership that addresses all of these issues. His work, compiled in consultation with the monks of Namgyal Monastery, who are specialists in the art of mandalas, offers a detailed written explanation of the visual “text” of one particular type of mandala, the Kalachakra mandala, and places it within the larger perspective of the Tibetan religious system.

The term Kalachakra, which literally means “Wheel of Time,” ostensibly denotes the name of a Tibetan tantric deity but actually connotes a larger realm of meaning created within the ritual drama choreographed by the artists of the Namgyal Monastery. In describing the Kalachakra mandala, which is only one aspect of that ritual, Bryant provides a step-by-step description of that choreography and explains how art is used in the Kalachakra rite of initiation. He offers chapters on the historical and philosophical background of the Kalachakra path and describes its transformation within the American context. He also provides a brief, general introduction to Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and devotes one entire chapter to the life of the Buddha. Academics may quibble that the author seems to take certain traditional myths at face value, yet he suggests that he is well aware of the myths’ historical contexts, and allows them to reveal the teachings in their respective idioms.

At first glance a narrowly defined description of an arcane ritual system, the Wheel of Time is actually a self-contained layperson’s introduction to the entire Tibetan Buddhist tradition that takes as its starting point the visual window offered by the Kalachakra mandala. Used in conjunction with several videos now available on Tibetan mandalas, The Wheel of Time presents a useful addition to courses on Buddhism, Asian art, or sacred art. Bryant’s text neatly supplements Sheri Brenner’s video Sand Painting: Sacred Art of Tibetan Buddhism, for example, which records the actual construction of a Kalachakra sand mandala. Traditional mandalas have gone high-tech in Pema Losang Chogyen’s Exploring the Mandala,which replicates meditational techniques as it transforms a two-dimensional mandala into a multistory palace with the assistance of animated computer graphics. The Wheel of Time Sand Mandala itself ably combines both word and image, as it is illustrated with more than 150 color and black-and-white photos and drawings. Books such as this are further evidence that the times have passed in which Western enthusiasts of Asian philosophy and religion have had to labor blind, as it were, poring over words and syllables while being denied the spiritual vision communicated by art and ritual.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.