The thing that has helped me most in this lifetime, aside from being born, is meeting a lineage holder of great wisdom traditions. But the being born part is pretty essential, and to be born means entering a lineage also: the bloodline.

The math is astounding if you think about it. Every human being has two biological parents. And each of them also has two biological parents, and so on, preferably with no overlap. Four grandparents, 8 great-grandparents, 16 great-great-grandparents, and so on, so that soon we are looking at 524,288 great-grandparents to the 17th degree all leading up to the creation of you. And that’s just going back 475 years. It’s possible that some of those half million people do overlap when we get back to the tribal days of cousins marrying cousins. Tribal days aren’t too far back in my family; my Auntie Violet ran away from home when she was promised to her own uncle.

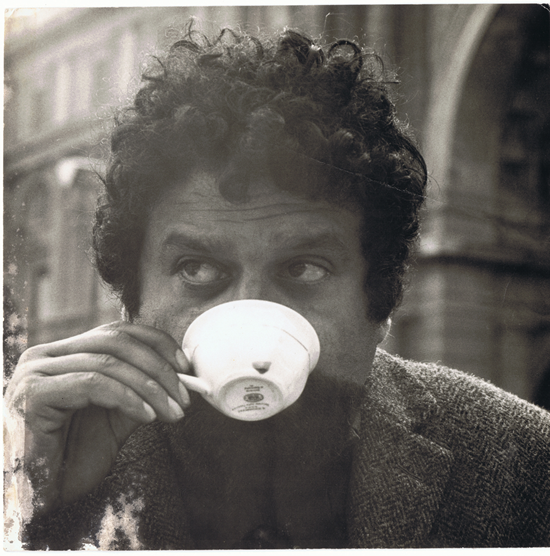

In my lineage, half of those people are from Europe (Basque and Welsh) and half are from the Middle East. My father was an Iraqi Jew—an abstract artist by trade, but also an artist in the kitchen. He was a famously good cook. People would drive for hours to sit at his table, usually fleeing in tears at the end of the night, but that’s another story.

I don’t know what the Jews of Mesopotamia ate for dinner, but the meals my dad whipped up (fiendishly, obsessively, impatiently, full of delight) had a genius to them. There was something about the way he used lemon and herbs that sent one back in time. His chicken soups, his daily batches of bread, the endless eggplant experiments. The house was always filled with amazing smells mixed with sawdust and turpentine.

After dinner he would make mud coffee (botz)—espresso ground chicory boiled in a pot of water with a few cardamom seeds and poured without a strainer into mismatched cups. It was delicious paired with his extraordinary baklava. Everything he served was as close to farm-to-table as he could make it. He would drive us to local farms in his beat-up purple Gremlin looking for someone to sell him eggs. We milked goats. He made yogurt and pickles. Our refrigerator was a 10-year-old’s personal nightmare. All I wanted was a bowl of Cocoa Puffs.

But now I can appreciate his efforts. This is my lineage. These flaky Middle Eastern delights, the hot and cool flavors, the hibiscus lemonade, the watermelon with feta. Also the fiery temper, the appreciation of beauty and nature, the hunger for philosophical truths. Those were his hand-me-downs.

My father died in 2010, and I never learned his kitchen secrets. My brothers, however, managed to recreate one of his most famous dishes: spinach pie. His beautiful baking sheets full of pastry were a much-loved feature at our table, especially when we had big parties.

This year, coming back to America, I finally slowed down enough to receive the transmission from my brothers.

Yehuda Ben-Yehuda’s Famous Spinach Pie

Prepare the filling:

2 packages chopped frozen spinach

3/4 pound of feta cheese

1 package frozen phyllo dough

Lemon, cracked pepper, and za’atar, if you have it, which you should

1 stick of butter

Olive oil

Optional

My older brother Raphael suggested cumin.

1 medium onion

Mint

Dill

Putting it together:

If you are going to use onions—which my little brother Yoseff insists on, and which most probably my father included since he liked onions so much that he would bite into them as if they were apples—mince and sauté them until light brown.

Fresh spinach is good, but frozen spinach works better. If you use fresh, boil it until it’s completely soft, chop it finely, and squeeze every last drop of water out. If frozen, defrost and squeeze until totally dry. Soggy = bad. The cheese counter will probably have some deceptively similar looking fetas, so be careful when choosing your cheese. They vary a great deal. Go for a medium salty variety: Bulgarian is unusually good and firm. Mash up the feta with the spinach, lemon, pepper, and za’atar and blend evenly. Za’atar is a traditional Middle Eastern savory spice blend made with sesame seeds and a number of herbs.

I wonder what the ancients did without Zabar’s or the frozen food delicacy section of the supermarket. I think you’d have to be pretty insane to make your own phyllo dough. So just buy one package of phyllo and let it thaw out overnight in the refrigerator. This is an important step, because the dough is delicate; you don’t want it to get dry or mushy. Most come in 12″ x 18″ packages, so your pan can be either that size or half that size. You can use scissors to cut the dough in half for a standard 9″ x 12″ pan. You don’t need a very deep pan; a cookie sheet with a half-inch lip is perfect.

Melt the butter with a tablespoon of oil. Using a paintbrush (a new one, although I am pretty sure my father sometimes just took one from his studio, cadmium red be damned), paint the bottom of your pan with a generous layer of butter. Separate the phyllo into two even piles. Cover one with waxed paper or a damp paper towel. Work fast so that it doesn’t dry out. Place one translucent piece of dough down, paint with butter, then add another layer. The more butter between the layers, the fluffier it will get, and the more fattening. Once half the dough is down, spread the spinach mixture evenly, then add the second set of phyllo layers on top. Sprinkle with sesame seeds or za’atar.

Make sure to cut the pie before placing it in the oven. We like diamond shapes, but square is good too. Bake at 350 degrees for 20–25 minutes or until the top is golden brown.

A pie this big will feed about ten people. You can easily freeze and reheat later.

Now it’s time for the new generation to innovate, so last winter, when we ran out of spinach we tried making one with kale and butternut squash instead, and it was delicious. We threw in a few toasted walnuts. But biting into the delicate original brings me home, sends me back in time, links me to that crazy man who made me.

My teacher was speaking to some of Trungpa Rinpoche’s students last summer, and he said that when Trungpa Rinpoche wrote in the colophon to The Rain of Wisdom “This little one was born as your great-grandson,” he was speaking to the great teachers Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa, Mila, and Gampopa. Rinpoche added, “Similarly, Trungpa Rinpoche’s students and the second generation of so-called dharma brats can be proud to claim that they are the great-great-great-grandsons or daughters of Tila, Naro, Marpa, and Mila and of the amazing, illustrious, and luminous lineage gurus. You cannot afford to forget their names.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.