That meditation is a moral practice, not just a psychic one, was not immediately clear to me when I began to sit. I understood intellectually, but not intuitively, that Buddhist psychology defines an intimate relationship between our treatment of others and the unfolding of mindfulness. Only recently on a retreat did I begin actually to experience the relationship between metta (lovingkindness) and the varied states of meditative concentration, to experience the impact of one’s wishes for others on the actual meditative states of mind. Then I began to grasp that the act of meditation, far from being a purely psychic exercise, actually draws moral practice and unfolding insight into a continuum.

From there to a political commitment is not a stretch. It’s significant to me that my dharma teachers first went to India in the early ’70s, part of the same leap of countercultural radicalism that continues to provide liberations of gender, education, sexuality, and spirituality even now. This, alone, ties politics and American Buddhism intimately together. Some time ago my work led me to interview a person who, throughout the ’70s, had participated in the Weather Underground’s bombings of political targets across America. What, I asked, is the difference between your leftist radical violence and that of, say, the right-wing violence of the Oklahoma bomber? My interviewee answered: “We were motivated by love; he by hate.” Perhaps that explains why hundreds died senselessly in Oklahoma while the Weather Underground made every effort to avoid harming people in their bombings.

The answer illustrated for me how a Buddhist morality, focusing on motivation, explains politics in a way that cuts through ideology and party loyalty. Regardless of party, regardless even of the particular solutions they propose, it is possible to identify those politicians motivated by compassion, by a real desire to relieve the pain of individual humans – and to distinguish them from those motivated by ideology and self-interest.

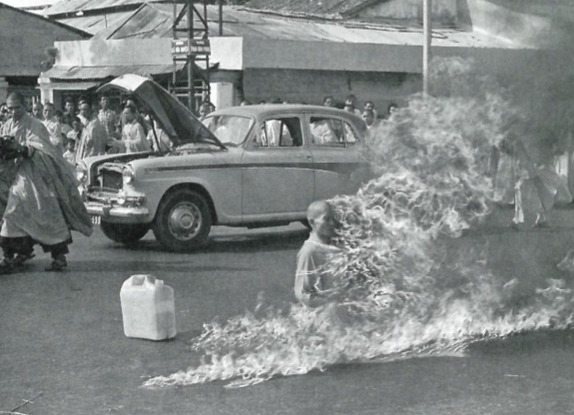

And there are, in politics, real heroes, among whom one can count many who incarnate the nexus of Buddhism and politics. From the beautiful Vietnamese monks who immolated themselves to protest the American intervention in Vietnam, to Aung San Suu Kyi, who learned to meditate while under house arrest for her challenge to Burmese authoritarianism, to the work of the Dalai Lama on behalf of the exiled Tibetan community, there are minds committed to both awareness and political action.

When we vote in even the compromised approximation of democracy that we enjoy in America, I think we recapitulate the entire progress of human civilization from slavery toward freedom. This can’t blind us to the injustices suffered by those Noam Chomsky calls the “restless many,” lost among the “prosperous few.” But to be both American and Buddhist means appreciating a great American myth: the old story of the farmer and his wife who, on election day, get into their cart and drive their horse fifty miles to the nearest town, an all-day trip, to vote. Arriving, the farmer votes Democratic, the wife Republican, and they start off on the long trek home again. Yes, they’ve accomplished nothing, each vote canceling out the other. And yet, in exercising an act of such fundamental idealism, I believe that they embody a deeply Buddhist notion: faith in the possibility of freedom.