On the day of my ordination, I arrive at Wat Phra Singh, the Royal Temple of northern Thailand, slightly hungover, fighting a losing battle with my clothes. I am draped in yards of heavy white cotton that indicate little intention of adapting to Western body movement. How do I stand? I wonder. Where do I put my hands? What if the entire outfit falls to the ground, leaving me naked before the crowd?

I have little idea what being a maechi, a Buddhist nun, entails. I just know that I must do it. I’ve known since the first moment I saw Wat Thamtong, the Temple of Golden Caves, one afternoon a few weeks ago. My professor and sponsor Ajahn Boon and I had stumbled out of the mountain pass and into the long, narrow grounds with their rushing streams and ivory butterflies. As I stood panting, I knew that this was where I would live.

* * *

This is just a research strategy, I try to reassure myself. For the past few months in the University of Wisconsin’s College Year in Thailand program, I’d read the sparse literature available about maechi, planning a groundbreaking fieldwork project on the identities and self-images of Thai maechi. I’d withstood the barrage of prejudice against the wisdom of female ordination.

I had visited famous wats and interviewed residents. When Ajahn Boon suggested that true anthropological study required undercover work, I leapt. Asking myself “Why not?” I had willingly chosen this white, unfriendly disguise.

My decision to ordain seemed to have taken on a momentum of its own. After studying and attending so many lavish monks’ ordinations, I admit I’d become a little resentful on behalf of the maechi. A small boy becomes a novice, and the entire village rejoices. Women, on the other hand, are supposedly weak, worldly creatures, unfit for spiritual endeavor, their ordination a condemnation of the family system. No party for us.

But Ajahn Boon did something amazing. Using his status as a former abbot and my ambiguous status as an outsider, he’d arranged for a full, formal ordination ceremony to be conducted by the abbot of Wat Phra Singh, after which I would reside at Wat Thamtong. Ajahn Boon wanted to use this as an opportunity to raise the visibility of women in Thai Buddhism. No ritual for women had ever been held at the Royal Temple. Suddenly, I was a vehicle for advancing a social agenda! Of course, I had hoped that my body of work would serve this purpose, but I hadn’t expected that my actual physical body would. I am most certainly the first Black, female, Thai-speaking, sarong-wearing, wat-going foreigner, or farang.

* * *

All December, a month prior to my ordination, Ajahn Boon took me to as many different ceremonies and wats as possible, so that I could decide whether I wanted to ordain.

One afternoon, at the invitation of Maechi Roongduan, a charismatic, college-educated nun I had met the previous week, we took a bus to Wat Thamtong, rumored to be one of the most welcoming residences for women.

A profusion of vegetable gardens and flowers turning their faces to the east signaled the wat entrance. We found ourselves in a cool garden surrounded by bamboo and pastel cages of songbirds. As we crossed a tiny footbridge,

I felt I was entering an ancient Japanese woodcarving.

To our right, across another bridge, the monks’ side of the stream exploded with color and activity: Bare-armed, they bustled about in the bright sunlight, hitching up their saffron robes as they churned the packed earth with brooms or hoisted buckets of water up from the rushing stream.

In sharp contrast, the maechi quarters directly before us were shielded from the sun. Lush, tangled greenery dominated the landscape; pale butterflies the size of two human hands flitted in and out. Silent women swathed in white drifted slowly through the shade. Others sat meditating in open-air pavilions. At the end of the rows of guti, private meditation huts, I glimpsed the entrance to the forest.

As if by magic, Maechi Roongduan appeared on the walkway, moving so smoothly she appeared to be gliding, her smile like the moon emerging from behind a nighttime cloud.

“So you came!”

We beamed.

She led us to the red-roofed, open-air sala, or gazebo, and we sat together drinking cool water. “What do you think of my wat?” she asked, and we soon learned that it was indeed her wat. She was the head maechi.

I glanced at Ajahn Boon to gauge his response. Maechi Roongduan couldn’t be more than thirty. The idea of this young woman with perfect posture heading up a famed wat in hierarchical Thailand was amazing.

I wondered how she negotiated governing women who were older (as most maechi were bound to be) and therefore socially superior.

Ajahn Boon was full of his usual questions about wat organization, and she offered to explain “the special rules.” “We eat a single meal a day, rather than the standard two,” she began, as I gazed out at the reds and golds of the monks’ quarters.

For the first time in months, I felt at peace. Real peace, not the momentary peace of having escaped my troubles in the States, disappearing into this farang life of exotic diversions and constant movement. True,

I loved nursing a salty limeade over a book in a Thai coffee shop where no one knew me. I loved hearing the tones of Thai trip and soar over my tongue. I loved showering from a barrel of cold rainwater before dinner.

But I worried about the inevitable return home. Thailand wasn’t real. I had nightmares about returning to college, where once more I would be pulled between my black and white worlds, my African and European heritage, my Western welfare upbringing and my affluent East Coast life.

Now all my fear melted away in the dreaming shade of this temple, this territory as split as my own identity, this yin and yang of landscape. There was just me, and this green and gold place. So this was peace. Perhaps Wat Thamtong possessed whatever it would take to heal what ailed me. Perhaps this place was real. All of a sudden I was clear, ready.

I turned to Maechi Roongduan and Ajahn Boon, unable to stop myself from interrupting their conversation. “I’ve finally decided,” I blurted out, not even knowing if my plan were possible. “I want to ordain. Here.”

* * *

On my ordination day, the crowd is a mixture of Westerners and Thais: my five fellow students—Jim, Angel, Eric, Francis, and Scott; faculty and staff, students and travelers we have befriended; Thai host families.

When I appear, the knot of people rushes forward. “Your hair!” comes the cry from those who missed the head-shaving ceremony last night. After my host mother made the “first cut,” ensuring that the merit of my actions will accrue to her and my host father, a professional barber shaved the rest, the first step in indicating the death of my lay life and the rebirth of my new. “Look at your robes!” They surround me, pelting eager questions. I smile, feeling too goofy to merit all the attention.

Grateful that today is a day for ceremony, for strict attention to the intricacies of Thai ritual, I place my palms together in a steeple and bring them to my face while bowing. The gesture, known as wai, indicates both greetings and thanks. As the head is sacred and the feet profane, the higher up the hands touch the face, the greater the respect shown. Fingertips touching the bridge of my nose, I thank each elder for coming.

At the end of the line stands a professor notorious for his glowering disapproval of Westerners. Though we issued an open invitation to the entire Social Sciences Faculty, our host department, I’m so surprised to see him that I stop short for a heartbeat and let my hands drop. True to form, he glares as I approach and thrusts out a fist as if to ward me off. I falter, feeling my sarong slip. Why has he come?

It takes me another heartbeat to see the bag dangling from his extended fist, even longer to realize that he is offering a gift. The sarong unfurls itself a bit more. At the back of my mind I remember something in one of my Buddhist texts exhorting postulants not to be concerned with matters of food and shelter, but to accept such offerings with the equanimity of one who could just as easily go without. I manage to wai and touch the bag, indicating my acceptance. I am not supposed to be toting around merchandise and so fight the urge to look inside.

Moving as deftly as a Thai, Jim glides up behind me, slides the gift out of the professor’s grasp. Acting on my behalf, he offers the bag around. The other guests peek inside, ooh and aahtheir approval.

I look up to see Ajahn Boon standing near the temple stairs with the abbot. He gives a quiet nod.

* * *

The night before my ordination, after my head-shaving ceremony, we had had a real American night, gorging on chocolate chip cookies, smoking, watching the Jiffy Pop from my Christmas care package rise, rewinding An American Werewolf in London and playing it back not once but twice. Everyone, including me, kept forgetting I was bald and then remembering, gently fingering my head.

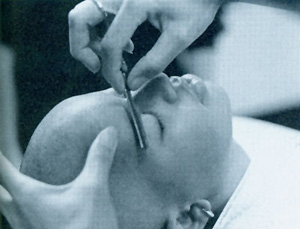

I know all this, but the last thing I remember clearly was holding my breath while the barber, unusually silent and serious, cleaned the stubble off my head with a glittering, old-fashioned hand razor, the kind you sharpen with a strop. He then laid me down on a vinyl table, cradling my head softly in the curve of his palm. With a delicate thumb pressing against my temple, he scraped away my eyebrows with the razor, like a caress. I remember sitting up and gazing shyly in the mirror. The person peering back was finally unlike my previous self, almost as calm and sleepy-looking as a maechi.

* * *

Ajahn Boon signals the twenty-six people who have come to witness my ordination that we are about to begin. He then beckons me to come greet the abbot. I wai, hands high on my forehead, and thank him for agreeing to honor me with this unprecedented ordination.

At the doorway to the temple, we take off our shoes and kneel, entering the cool, dim interior on our knees. I bite my lip and shuffle forward, the stone floor cold and hard through the slippery sarong. Behind me, I can hear laces untying, Velcro tearing, the slap of sandals falling to the ground.

By now my heart has clawed its way out of my ribcage and into my throat, where it quivers fitfully, planning escape. We pay silent obeisance to the Buddha, foreheads touching the bare stone floor three times. With an expert flick of his saffron robes, the abbot shifts around so that the 1,500-year-old Buddha statue hovers behind him. I kneel facing their combined authority, hands in front of me, palms together.

My host mother kneels to my right, Ajahn Boon to my left. The guests crowd inside the door, forming a half circle behind us. My host mother passes me a footed brass tray with three sticks of incense and three fresh-cut flowers.

Bowing to the abbot, I place the tray before him. He touches the offering, accepting it, and asks the ritual question: “Maa tommai?” Why have you come?

I reply in Thai: “I have come to request ordination as maechi.”

He asks: “Who will sponsor this individual?”

Ajahn Boon gives the ritual response: “I am the one.”

The abbot nods, pronouncing to the assembled company, “This is a good thing.”

Three days before my ordination ceremony, Jim asked me why I’m ordaining. Now that it’s down to the wire, why have I decided to go through with it?

I didn’t know. At first, while planning in the abstract, I thought becoming a maechi would be “different.” A cocktail party starter. An experience that would benefit both me (developing discipline and peace) and my field research (if I presume to be able to explain the lives of those I study). Something to look back on. Something to make me brave.

I’d been toying with the idea ever since Ajahn Boon said that I couldn’t write about something I hadn’t experienced. Of course, I could never be a Thai woman, but how could I even hope to render the interior life of maechi on the page if I didn’t have a language for it?

I agreed because it’s a strange place to stand—the Black woman anthropologist. I didn’t want to be a detached scientist reducing Asian women to objects of study; I wanted to utilize my ability to enter cultures, my own multicultural perspective to understand, translate, bridge. Participate.

* * *

The abbot leads me in a triple recitation of the Threefold Refuge:

Buddham saranam gacchami.

(I go to the Buddha for refuge.)

Dhammam saranam gacchami.

(I go to the Dhamma for refuge.)

Sangham saranam gacchami.

(I go to the Sangha for refuge.)

I am then instructed to pay homage to the Buddha three times:

Namo tassa Bhagavato Arahato

Sammasambuddhassa!

(Praise to the Blessed one, the Noble one,

the Perfectly Enlightened one!)

Finally, I take the Ten Precepts (sila), or rules of training, for novices and maechi. Some women now take these vows in Thai, but it has been a point of pride with me to memorize the traditional Pali. Though I know the ceremony by heart, my voice trembles so much that I can hardly speak. The steeple of my hands bobs frantically up and down. I hadn’t expected this nervousness. Several times my host mother has to prompt me as I declare my intention to undertake the rules of training:

(1) To refrain from killing any living creature

(2) To refrain from stealing

(3) To refrain from contact with men

(4) To refrain from lying and false speech

(5) To refrain from consuming intoxicants which cloud the senses

(6) To refrain from consuming food at inappropriate times

(7) To refrain from using scent and makeup

(8) To refrain from singing, dancing and watching entertainment

(9) To refrain from sleeping on soft or high surfaces

(10) To refrain from touching money

When the ceremony is translated into Thai, several people murmur surprise. The last precept, optional in modern times, is regarded by many as being unnecessarily difficult for women, given their lack of social support. Again, a point of pride: I am the first woman to be ordained in Wat Phra Singh; I intend to do it right.

After accepting my vows, the abbot switches into Thai and begins to advise me on monastic life. He points out that the precepts are called “rules of training,” indicating that they are guideposts in an ongoing practice rather than hard and fast vows. Unlike Christian vows, which are concerned with sin, the purpose of Buddhist precepts is to clear the mind for contemplative practice. It is perhaps the same logic that allows me to think of myself as a visitor to Buddhism—I will keep sila, just as any good houseguest adheres to the rules, but still be me, untouched, on the inside.

The abbot continues. Besides the Ten Precepts, countless other strictures govern maechi posture, attire, deportment, communal living, and social interaction. This personal attention, in addition to the standard ordination script, is an honor. My senses, however, are shutting down on me. I have no idea what the abbot says.

As soon as I emerge, squinting, out of the dim temple and into the overwhelming brightness of day, I know that everything has changed. It’s not simply that the heat of midday has arrived in our absence, nor that my legs fell asleep during the ceremony and I can no longer feel them. It’s more. I expected what little change there would be to develop gradually, through monastic living, over time. I didn’t expect to feel so instantly changed inside. I stare at the brass tray in my hands, and it’s as if I’m watching myself from a great distance, as if I have left my body and float suspended above it.

“Put these on.” My host mother crouches at my feet, a pair of new sandals in her hands. “You’re no longer human,” she explains, though I have never heard anyone say this of maechi, only of monks. “You can’t wear your old shoes.”

I hover above the cool stone, unable to tell if I’m walking or standing. I blink repeatedly, frightened at the sight of a Thai elder kneeling before me, her hands near my profane feet. Despite the commonly held views about maechi, being one suddenly means something. This single moment, the flutter of her pale fingers near my dark toes, indicates just how far things have moved in thirty minutes.

I glance at Scott, Eric, Jim, Francis, and Angel. Their faces shimmer like the horizon in heat, distorted and distant. From their odd, nervous glances, I realize that in their eyes I, too, have become a stranger, something foreign. I look away.

I don’t know whether to smile or stand stern and detached like the abbot. I feel suspended somewhere between laypeople and the ordained. I will soon learn that this is indeed the reality of all maechi. Women in white who do not speak. Neither inside nor outside of society, they are no longer ordinary women engaged in life. However, they will never be considered the holy creatures monks are. I feel alone and yet part of them. Simply uneasy, with one new sandal, and one old. ▼