I was standing in the back corner of the well-appointed front room of the San Francisco Zen Center Guest House. My pants were down around my ankles, and I was davening—rocking back and forth in the rhythmic movement that traditionally accompanies Jewish prayer—as I recited from the copy of Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint that I held open before me. In the center of the spacious room, near the high bay windows that look out from the renovated Victorian’s second floor, four tall, fair-skinned Zen Center priests in golden robes stood, erect and dignified, conferring intently in hushed voices. Noticing my presence, they turned, and each fixed a stern gaze upon me. I felt that I should stop, but I couldn’t. In fact, flushed with self-consciousness, my davening became more rapid and my chanting louder, until, frantic, my voice was no longer recognizable as my own.

That was when I awoke. It was nearly pitch black, and I was in a strange bed. I couldn’t recall where I was. The scent of the sandalwood soap on the nightstand and the brushing of the branches against the windows were the first clues, and in a minute it came together. I was in the same guest house I had been dreaming about, though in a different room. It was the second day of the Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh’s first teaching tour of American dharma centers, a tour that I had spent much of the previous year organizing and on which I was now, in the spring of 1983, accompanying him as his assistant. I sat up in bed, clammy with sweat, and to the surrounding darkness, the chilly San Francisco night, and to myself, I for some reason muttered, “I’m Jewish.”

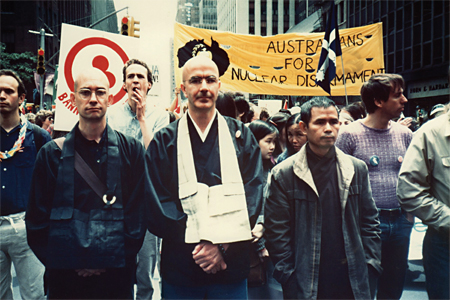

This was obviously an odd thing to say, and I’m still not really sure why I said it, but it had the calming effect of bringing me back to myself. I certainly needed that kind of help on that particular night. Although I was at San Francisco Zen Center, I was in extremis. The previous June, at an interfaith conference on nuclear disarmament in New York City, the Zen Center’s abbot, Richard Baker Roshi, had met Thich Nhat Hanh and invited him to come from his home in France to San Francisco to be a guest teacher at Zen Center. I had attended the conference as well, and at its conclusion, I was introduced to Nhat Hanh, or as I learned to call him, Thay, an affectionate Vietnamese Buddhist term for a respected teacher. I spent a good part of the next week with Thay Nhat Hanh, and after we had spent several days together he told me of Baker Roshi’s invitation, which he was all but certain he would accept. Then he said that he wanted me to organize the visit.

This last thing really threw me for a loop. Up until then, I had thought he was, more than anything, just thinking aloud, with me as a sounding board. Talking with him that way was pretty terrific, actually. Thich Nhat Hanh was, is, an extraordinary man: an eminent Buddhist teacher, a figure of considerable stature in Vietnamese literature, and a man renowned internationally for his work for peace and social justice. He was fascinating, congenial, challenging, funny, and unpredictable, and everything had been going so well until he brought up this business about organizing his visit to San Francisco Zen Center. I just didn’t know what to make of that.

As Thay knew well, I was a student of Taizan Maezumi Roshi at the Zen Center of Los Angeles. I told Thay that, since Baker Roshi had invited him, it would be highly irregular for me, as someone from ZCLA, to have anything to do with organizing the visit. Thay assured me that there would be no problem, but I was not very assured. When I pointed out that Baker Roshi would likely not understand the reasons for my involvement— and why would he, since I didn’t understand them myself?— and might therefore find it intrusive, Thay simply said that I just needed to explain that this is what he, Thay, wanted, and then everything would be fine. I voiced my doubts, but Thay insisted. Either he didn’t get it or he didn’t care. Or maybe he did. I had no idea.

I thought perhaps Thay was asking me to plan things because I was outside the S.F. Zen Center orbit and he wanted the trip to include visits to other Buddhist groups. Or maybe it was because I was an organizer of the then-nascent Buddhist Peace Fellowship (BPF) and he hoped to reach out to Buddhist social activists. I asked him about these reasons, and he was amenable to pursuing both directions, but it was in a casual “If you think that’s best, then go ahead” kind of way. So that’s what I did: I went ahead.

After the disarmament conference, word of Thich Nhat Hanh’s upcoming visit spread quickly, and I was back at the Zen Center of Los Angeles only a short time before I began to receive calls and letters from around the country asking for, and occasionally demanding, a place in the itinerary. Within a few months, Thay’s two-week visit to San Francisco Zen Center had turned into a six-week cross-country teaching tour, with additional stops in Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Rochester, upstate New York, and New York City. I arranged for BPF to sponsor the trip, which in the short run gave me some organizational cover and in the long run would provide a structure for those interested in Buddhist activism to connect with each other. It was a monster to plan, taking up my nights and weekends for the better part of eight months. But it was marvelous.

Things at the Zen Center of L.A., however, had not been going particularly well for me, though I prefer to think this was not related to my involvement with Thich Nhat Hanh. For well more than a year, I had been bumping heads with several in the center’s leadership, and a few days before I was to leave to meet up with Thay in San Francisco at the start of the trip, I was summarily fired from the ZCLA staff. I hadn’t a clue what I would do when I got back. Or if I would go back. Or what.

So with the tour I’d been responsible for organizing about to begin, and the course of my life after it ended now up in the air, I was feeling a bit, you know, out of sorts.

The day after my dream, a documentary film crew was scheduled to come to the San Francisco Zen Center Guest House to film a discussion between Daniel Ellsberg and Thich Nhat Hanh. Joanna Macy, who was then just coming into her own as a voice for Buddhist activism, and her husband, Fran, a leader in the citizen diplomacy movement, were also to participate, but it was inevitable that the focus was going to be on Ellsberg and Nhat Hanh. Ellsberg, who had famously and courageously leaked the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War, epitomized the Western ideal of the political actor as a man of conscience. Thich Nhat Hanh helped pioneer— indeed, in the West his name was virtually synonymous with— the emergence of engaged Buddhism. How could one pass up an opportunity for such a meeting of the ways?

At least that’s what I thought when the idea was pitched to me about two months earlier by a documentary filmmaker. It sounded great, and even though Thay had been clear that his main interest for the visit was in teaching the dharma to committed students, I thought the idea worth running past him. In his letter back to me, Thay agreed to the proposal, though he betrayed no discernable enthusiasm.

I called the filmmaker and told him I had gotten Thay’s approval but that I now had to make sure it was okay with the people at San Francisco Zen Center. I also asked for and received his assurance that things would be kept simple and in every way not an imposition on Zen Center’s hospitality.

Taking this proposal to Zen Center was a delicate matter. The previous September, three months after the disarmament conference, I had flown up to San Francisco to meet with Baker Roshi about Thay’s visit. Early in our meeting, I said that I recognized the awkwardness of the situation and that during the San Francisco part of the trip I would, with a couple of specific exceptions indicated in a letter Thay had sent me, just try to stay out of the way. Baker Roshi accepted this, and while his displeasure with my involvement was palpable, we had come to what seemed a fair working agreement: while Thay was a guest of San Franciso Zen Center, the planning of his activities would be up to Baker Roshi. Now, in proposing this filmed discussion, I was breaking the agreement, kind of. Technically I had exceeded no boundary, but I was the one shuffling things along.

I ran the proposal up the Zen Center ladder, and word came down to proceed. As the day of Thay’s arrival drew near, new wrinkles began to appear in the plan for the filming. One camera would not be enough—would a second one be okay? More lighting would be necessary. A second assistant, and then one more than that, would be needed. The crew would need more time to set up. Each time I passed on a new request, I felt my ineffectualness once again confirmed. By the day of the filming, the whole thing had snowballed to comprise a six-hour block of time, a four-person crew, Zen Center support staff to help with the overloaded electrical circuits and other problems that had arisen and were bound to arise, and so forth. I had said that I did not want to be intrusive or disruptive, but I had succeeded in being both. I had fallen for the promise, and the thrill, of being part of a big event, and it had gotten the better of me. Still, while I might have screwed up, the event itself might, I hoped, set things aright.

That the anxious imagery of my dream had assumed a specifically Jewish caste was, I knew, connected to a contrast in how I perceived San Francisco Zen Center and the Zen Center of Los Angeles. I was not alone in this— others at ZCLA and even some visitors from other Buddhist groups had made mention of the same thing: San Francisco Zen Center had about it a very gentile feeling, and ZCLA was, in a word, very Jewish. I am not here talking about demographics— there were a lot of Jews at both places, as there were at most of the meditation-oriented Buddhist communities. Nor am I speaking in a religious sense, as few Jews at ZCLA were observant, and I imagine the same was true at SFZC. I am referring to something similar to what Lenny Bruce was getting at in his famous routine “Jewish and goyish.”

“If you live in New York or any other big city, you are Jewish. It doesn’t matter if you are Catholic. If you live in New York, you are Jewish. If you live in Butte, Montana, you are going to be goyish, even if you are Jewish.”

According to Lenny, Count Basie was Jewish, although he wasn’t, and Eddie Cantor was goyish, even though he was a Jew. Lime soda is goyish; black cherry soda is Jewish. And so it goes.

Jewish, in this sense, is not a matter of membership in a particular group but a placement in a string of binary oppositions plucked from an amorphous cluster of associations. But whereas Lenny’s binaries reflect his own Jewish partisanship, I mean nothing of the sort. It’s just that something about SFZC made me feel less like I’d come there from another Zen center than like I’d been driven up from Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn in a cheap suit, carrying a suitcase full of fabric samples and deposited in some Episcopal enclave in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Back then at least, the atmosphere at San Francisco Zen Center was far more contained than that at ZCLA. Practice was more formal, people were more reserved, and they were far more proficient in the elaborate protocols of Zen practice. ZCLA, on the other hand, was embarrassingly sentimental, maddeningly argumentative, and we seemed never to meet an idea so harebrained as to not be worth pursuing. Just like my family.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s talk in June 1982, on the third and final day of the Reverence for Life Conference in New York City, was something remarkable. Even while he was still being introduced, Thay began walking, at a snail’s pace—which I soon learned was his normal cruising speed—up to the speaker’s podium. Rather than stand behind the podium, however, he stopped in front and spoke from there. He spoke gently, in lyrical cadences, yet there was steel in his words. There was a similar pairing in the commanding presence he projected— light as a feather yet solid as rock. Within minutes the audience was transfixed.

He expressed himself in delicately accented, down-to-earth language, only occasionally citing explicitly Buddhist sources. He used stories and personal anecdotes to illustrate his points, he casually posed brief contemplations, and he read several of his own poems to stunning effect. At the heart of his talk, however, was a well-known passage from the Pali canon:

When this is, that is.

This arising, that arises.

When this is not, that is not.

This ceasing, that ceases.

This is the most succinct formulation of the Buddhist teaching of paticcasamuppada, or dependent origination, one of Buddhism’s core ideas. Starting with this most simple of expressions—When this is, that is—Thay explicated dependent origination as a vision of radical interdependence, or what he called “interbeing,” in which all beings support and are in turn supported by all other beings. This elaboration of paticcasamuppada encompassed the foundation, the practice, and the fulfillment of spiritual life.

In the film Shakespeare in Love, there is a crucial moment immediately following the conclusion of the debut of Romeo and Juliet, the play set within the movie. After the final words are spoken, the audience, held in the thrall of a play that has shown “the very nature and truth of love,” is struck silent for a second or two before erupting into applause. That’s how I remember the brief, spellbound silence immediately following Thay’s talk. It was a cinematic moment. He had, one might say, shown the nature and truth of interdependence.

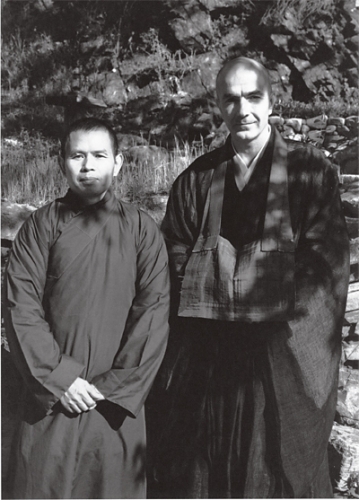

During the conference, I had struck up a friendship with two of Thich Nhat Hanh’s disciples, his longtime co-worker Cao Ngoc Phuong (who now is known by her monastic name, Sister Chan Khong) and his niece Nguyen Anh-Huong. Shortly after Thay’s talk, they told me he had asked to meet me that night, after the closing ceremony. They didn’t say why, and I, glad for the opportunity, didn’t ask.

After the conference’s closing ceremony, Sister Phuong led me through the crowd milling about on the granite steps outside the church where the conference had convened. When we found Thay, he and I greeted each other with short bows. Then he reached out as though to shake my hand, but instead he simply held it and peered up at me. He had warm brown eyes and finely articulated features. I held his gaze and waited, uncomfortably, for him to say something, which he did not. After maybe five or six seconds—real seconds, not writers’ ones—he tucked my hand under his arm, turned, and began walking down Park Avenue. We walked slowly and silently, and it took me an embarrassingly long time to figure out—Oh, I get it!—that I was supposed to be doing walking meditation. Sister Phuong and Sister Anh-Huong preceded us, at a similar pace, by about ten yards. At some point, Thay informed me that we were going back to the apartment at which they were staying to talk and have tea. Their guest digs were not that far away, but it took us forever to get there.

The apartment was huge and expensively furnished and obviously had been lent to the conference organizers by someone extremely wealthy. Everyone disappeared for a few minutes while I tried not to get lost as I explored the vast reaches of the living room. Soon Thay returned and seated himself crosslegged on a long green sofa. Sister Phuong brought tea, and then she and Sister Anh-Huong said goodnight. From his perch on the sofa, Thay patted the cushion right beside him, indicating for me to sit. It was close quarters. Then, without preamble, he locked me in his sights and asked, “Are you happy?”

This was definitely not small talk. In fact, it didn’t exactly fit any category of talk I was familiar with. It had some of the flavor of a Zen master’s demand to “Show me your original face,” but it was also quite different. Nor was it the same as talking with a friend, being interviewed for a job, working with a therapist, or being interrogated by the Special Branch, though it had elements of each of these. Still, for some reason I felt I had a sense of the spirit of the question, and so I gave my best answer.

“Yes,” I said, my usual chattiness in abeyance for the moment.

Thay seemed to chew on that for a few seconds. So did I. Then I explained a bit more, but not much, and Thay took it in without comment. He then asked, “Have you ever thought about suicide?” I told him I had, when I was nineteen and had sunk into deep melancholia. Again he simply heard me out, then asked another question. This is how things went for the next hour or two. Thay would ask a question (“What’s the most important thing for two people in love?” “What do you like to do for fun?”), and I would answer as best I could. Occasionally he would remark briefly on what I’d said, but usually he’d just listen.

I was, of course, aware of how weird the whole thing was, but I sensed nothing threatening about it. The very strangeness of the exchange made it all the more intriguing. And there was this: in some way I couldn’t really pin down and despite appearances, I felt that the communication was mutual, that it emerged from a shared, unspoken recognition of an underlying affinity.

Eventually, Thay seemed satisfied that he had learned what he needed to know, or maybe he just ran out of questions. In any case, he asked me if there was anything else I wanted to say. I felt obliged to come clean about a perplexing personal trait that I had long struggled with and that had caused more than a little trouble in my life as a Buddhist.

“I should tell you,” I said, “that I can be very stubborn.”

“Stubborn is good,” he said. Then he stood up, stretched, and said, “OK, the interrogation is over.” We both laughed at that.

It was very late, and as I readied myself to leave, Thay said he would like me to come upstate with the three of them for a few days. I figured they needed a driver, and I was happy to help out. Then he said, “If we are going to work together, there has to be more to it than just that you have something I want and I have something you want.” This seemed a reasonable, albeit peculiarly abstract, proposition, and I nodded my agreement. It was while we were upstate that he asked me to plan his visit to the States the following year.

About an hour before the discussion with Daniel Ellsberg and the Macys was to start, Thay asked me if I could suggest something they might talk about, and after giving it some thought, I said I could. In the mid-1970s, when tens of thousands of Vietnamese began fleeing their country by sea, many of those in the U.S. who had once worked together in the antiwar movement became bitterly divided over how to respond to these “boat people.” Some viewed them as mere economic refugees who were seeking new opportunity or attempting to regain the privilege they had enjoyed under U.S. patronage. Others considered them political refugees who were escaping the programs—forced labor zones, re-education camps, mass imprisonment and torture—of an oppressive regime. Many boat people drowned or starved in overcrowded and unseaworthy vessels; many were preyed upon mercilessly by pirates. Eventually they numbered in the hundreds of thousands, and most of them languished in refugee camps.

Some of Thay’s former allies in the American and international peace movements had criticized his actions on behalf of the boat people as politically naive, questionable in motive, and worse. It was an ugly episode for a lot of people, and a bitter one for Thay and Sister Phuong.

Some months earlier, I’d heard Daniel Ellsberg speak about issues in the aftermath of the war. Thay and Ellsberg seemed to be in fundamental agreement about the boat people, yet they had arrived at their conclusions in very different ways, and I felt this could make for a fruitful discussion. I thought that by addressing this specific issue, they might bring greater understanding to some of the perennial problems that crop up when political concerns collide with moral ones, and in the process perhaps they might heal old wounds that in some quarters still festered. Thay thought it a good idea, and to tell the truth, I was pretty pleased with myself for coming up with it.

The discussion was being filmed in the front room of the Zen Center Guest House—the very room I’d dreamed about the night before. The room was packed with film equipment, electrical wires, and maybe thirty people, who filled in every inch of space that was left. In the center of the room, Daniel Ellsberg sat stage right, the Macys were in the middle, and Thich Nhat Hanh completed the arc. Thay got the ball rolling.

“I want to ask Daniel Ellsberg: Why does the American peace movement have no compassion?” That’s what he said. He might have said it a little differently; he might have said a little more; but that was pretty much the crux of it.

My guess is that no one there, except me and maybe Ellsberg, knew what this was about. But everyone recognized the peculiar note that had been struck. I just cringed: Oh no. Oh no. This is not what I meant. This is not what I meant at all. A knot began to form in the pit of my stomach.

I hoped that Ellsberg would find a way past this. Not that it would be easy. He had just been blindsided, targeted unfairly with one of those questions one can’t possibly answer because the premise itself is so askew. But if anyone knew how to think on his feet, it was Daniel Ellsberg. Maybe he could set this thing aright.

What happened next, however, couldn’t have been worse: Ellsberg took Thay’s question personally and responded defensively. He answered the unfortunate challenge with a few of his own, in particular, he challenged Thay’s passing judgment on who was and who was not compassionate. From there, the nastiness and absurdity just accelerated. Here they were, two great and good men, arguing like kids on the playground, about compassion—who had it, who had the right to talk about it, who really understood what it was. It was their pain talking, and neither seemed able to see it or admit it or get a handle on it.

Every so often, Fran or Joanna would jump in to try to change the subject, but Ellsberg and Thay weren’t about to fall for that. They were Ali and Frazier, LaMotta and Robinson, just waiting between rounds for the bell so they could get back to pummeling each other. There was no stopping them; they were going to go the distance.

Finally, and mercifully, it was over, and there followed another cinematic moment, but one very different from what had followed Thay’s talk at Reverence for Life. This was like the audience response to the performance of the jaw-droppingly awful musical number “Springtime for Hitler” (“We’re marching to a faster pace/Look out, here comes the master race!”) in the play within Mel Brooks’s movie The Producers: stunned silence and disbelief.

Soon people began slowly to file out of the room, but in a kind of daze, much like they were walking away from a pileup on the interstate. Joanna approached me and in a shaky voice asked, “What about paticcasamuppada?” It’s not often one gets to be part of an unqualified and incomprehensible debacle.

Needless to say, I was feeling just horrible about my role in the whole thing. I had pushed the event through, and I had suggested the starting topic, and while it was true that I had no control over the turn the discussion had taken, there was no getting away from the fact that my judgment had been just abysmal. But oddly enough, I also felt a sense of relief. For while that part of myself represented by those upright Buddhist priests was glaring down at me more harshly than ever, that davening Jew had hitched up his pants and stepped out of his corner and was ready for action. One must, after all, move ahead from where one is, not where one would like to be.

Everybody, even the best of us, will sometimes behave ingloriously, and to think otherwise is to be hemmed in by vanity. As sad sinners wandering through samsara, one of the few things we can count on is that we are on occasion going to screw up miserably. For those of us who are exceptionally reliable in this regard, it is nothing less than a saving grace, is it not, that in our guise as bodhisattvas, falling down on the job is the biggest part of the job, and sometimes, somehow, failure, if allowed to do its work, can actually be surprisingly emancipatory. It can even help make us whole. We have to try to be better—wiser, kinder, more generous—people, but mostly there’s no getting away from our embarrassing, maddening, harebrained selves. There’s a joke that is a good reminder of that.

One day, in the middle of service, the rabbi calls out, “Oh Lord, I’m nothing, nothing. I’m nothing.” As the rabbi continues, the cantor joins in: “I’m nothing, oh Lord, nothing.” In the back of the synagogue, the shamus—something like a temple janitor—broom in hand, is so inspired by this display of humility before the Almighty that he too joins in: “I’m nuttin’, Lord, I’m nuttin’.” The rabbi looks up and eyes the shamus disapprovingly. He then turns to the cantor and says, “So look who says he’s nothing.”

While it’s true that spiritual aspiration is an inestimable good, sometimes there’s nothing better for the soul than falling flat on your face. You have to work with what you’ve got, and what you’ve got is who you are, and there’s no way around that.