The workplace presents us with some tough challenges that require both professional skill and spiritual wisdom. Giving difficult feedback to a colleague, confronting an offensive boss, motivating a disillusioned coworker, losing a job, exposing a fraud or a petty office theft—such challenges are real and unavoidable aspects of our jobs. Managing such difficulties can make us feel anxious or disillusioned and, at times even arrogant, inadequate, or fearful.

But navigating such workplace difficulties need not be distressing. In fact, managing conflicts skillfully can be a powerful opportunity for personal and professional growth. What I’ve found particularly useful is a traditional Buddhist way of working with conflict: the Mahakala method.

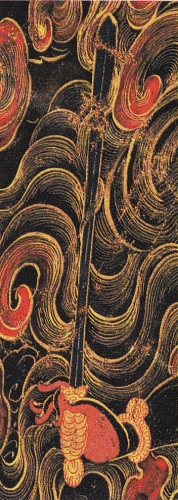

Carrying a weapon in each of his four arms, the Tibetan deity Mahakala strikes a threatening pose. But Mahakala is actually a protector deity, and meditators have long relied on his powers to help them through difficulties of all kinds in their daily lives. He represents our natural ability to promote what is sane and decent and to eliminate what is unreasonable and harmful. His weapons—a medicine-filled skull cup, a hooked knife, a sword, and a trident—represent four inner resources, traditionally called the “four actions,” for skillfully working with conflict by pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and destroying.

Being impulsive or arrogant about what is right and wrong, especially during a conflict, can be disastrous. We may think we’re doing what is best for everyone, but often we are only demonstrating our own inflexibility and aggression. Mahakala’s fierce pose reminds us to be alert and mindful—to manage conflicts precisely, and to act with sanity and decency. Here are the four principles that underlie the Mahakala method:

1. Pacifying

Pacifying, represented by the skull cup filled with a calming medicine with magical properties, is our ability to work with conflict peacefully. Often we view business conflicts as confrontations. We tense up, wanting to prove our point or possibly show our coworkers how clever or tough we are. Sometimes we may try to escape the discomfort (and avoid blame) by resorting to excuses or white lies.

Mahakala’s pacifying weapon is our ability to drop this struggle altogether. Pacifying starts with acknowledging that our defensiveness is an unnecessary psychological weight that is getting in the way of working with the problem. Rather than focus on winning or losing, we can permit our defensive energy to transform into curiosity about the conflict itself. What is actually at stake here? What does the other person really want to say, to see happen? Why is the other person so upset, and what would eliminate this distress? Listening, asking questions, appreciating the other’s point of view, expressing gratitude, and seeking clarification are all pacifying activities.

We are all familiar with the coworker who uses all the milk in the office refrigerator but never seems to have the time to replace it. Rather than quietly fuming or scolding our colleague, we can defuse the situation. The Mahakala method suggests that we simply ask: “I am going down to buy some milk for the refrigerator; is there anything I can get for you?” By expressing an open curiosity and generous spirit, we also model for our colleagues the type of behavior we would prefer them to adopt.

2. Enriching

Enriching, represented by Mahakala’s hooked knife, which transforms raw material into nourishment, is our ability to support and encourage others—even our adversaries. Typically, we protect our own territory in a confrontation, preserving our resources, voicing our opinions, achieving our objectives. When we enrich a conflict, we recognize that we need not limit ourselves to such a narrow view. Providing perspective, seeking options, promoting win/win solutions, offering assistance, revealing commonalities, making concessions, telling stories that clarify a point, building alliances – all these are enriching activities. Once we’ve employed the first action of pacifying conflict with gentle curiosity, we can promote a sane resolution by inspiring others to feel empowered and supported.

I recall an IT project manager, Mark, from my time on Wall Street. Mark had moved up the ranks quickly, becoming the darling of the capital-market traders. He had an uncanny ability to work with the most complex real-time systems. Whether it was launching new fund products or indexes, upgrading finicky customized software, or just getting the network back up and running, Mark was recognized by senior management as the go-to guy. Needless to say, many of his colleagues grew resentful of Mark, seeing him as hogging the spotlight and out for himself.

What so impressed me about Mark, however, was not his technical skill, but his ability to enrich his colleagues despite their criticisms of him. At weekly IT meetings, Mark always made a point to thank those who had done the hands-on work. Often he would volunteer his own personal time to help a fellow project manager with a difficult problem. And he always had one or two interns on his team, teaching them and involving them in the complex work of keeping the trading desks up and running. Mark understood that technical brilliance was only part of being successful, and that it was in enriching others—encouraging their involvement, building alliances, and offering assistance—that he could find satisfaction and manage conflicts skillfully, disarming jealousy and competitiveness and enlisting support and mutual respect.

3. Magnetizing

Magnetizing, represented by Mahakala’s sword, which focuses attention, is our ability to attract resources during conflicts. Since we are willing to relinquish some of our territory when we enrich the situation, we can now invite others to make concessions, seek alternatives, or trade resources. By its very nature, conflict resolution requires compromise. By modeling our own resourcefulness first, we can then invite others to offer suggestions and share responsibility.

During the ’90s, profit margins and sales in the home movie-rental business were shrinking rapidly, and no amount of marketing seemed able to stem the tide—until a media executive made a truly magnetizing gesture. The executive discovered that customers hadn’t deserted the video-rental stores at all. In fact, the stores were packed with customers but they were leaving without renting films, because the films they wanted were unavailable. The executive had learned that customers tended to rent films within twenty-one days of their release on videocassette. The challenge, therefore, was to provide plenty of copies of “new release” films during that critical period.

The executive made a bold and magnetizing proposal to all major movie studios: They should provide rental stores unlimited cassettes of “new release” films for free. This would ensure that no customer would leave stores empty-handed, and sales and profits would soar for both the video store and the studio, which would share in the rental income. At first such a proposal seemed preposterous: Studios made money by selling videos, not by giving them away. But by inviting the studios to provide unlimited numbers of cassettes, the executive was magnetizing much-needed resources in a difficult situation. Rather than becoming hypnotized by the circumstances or defensive about industry criticism, the executive first pacified by observing closely what the customer wanted, and then magnetized by making an imaginative proposal. In the end, all concerned came out the better: The studios realized improved video income, the stores returned to profitability, and the customers got the films they wanted when they wanted them.

Of course, magnetizing need not be just corporate strategy. The supervisor who inspires employees to work late, offering an extra day off; the police officer who convinces kids to say no to drug dealers, letting them play late-night basketball; even leaving the extra penny at the cashier counter in order to borrow one later – these are all examples of magnetizing.

4. Destroying

The fourth action of the Mahakala is destroying, represented by the trident, whose three prongs destroy the three poisons of anger, greed, and delusion with one stroke. Because we have the patience and wisdom first to pacify, enrich, and magnetize, we establish the foundation for being firm and forceful, when and if necessary. Destroying is our ability to say no skillfully and precisely: to walk away from a bad business deal, openly disagree with another’s opinion, terminate a floundering project, confront a fraud, or close a struggling company. Destroying is our ability to take a stand—firmly and directly.

Often, when we feel defensive or mistreated during a conflict, we tend to misuse our ability to destroy. Angry words, dismissive attitudes, abrupt and harsh decisions all arise out of a desire to overcome the conflict rather than work with it mindfully. The Mahakala method suggests that we listen first, support others, and seek compromise before we say no—before we say “you’re fired” or “the contract is canceled.”

Unfortunately, destroying without listening, compromising, or offering helpful solutions has become an accepted and at times admired reflex among business leaders. Take, for example, the infamous “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap – the CEO who posed as Rambo on the cover of USA Today and titled his 1996 best-seller Mean Business. Notorious for his arrogance, tantrums, and short attention span, Chainsaw Al was admired on Wall Street in the ’90s because of his ability to ruthlessly “save” businesses. As a CEO, he showed no loyalty to workers or suppliers, no responsibility to the community, and no generosity to those less fortunate. He championed efficiency and brutality, and followed no principle other than short-term profits and cash for himself. There was no room for pacifying, enriching, or magnetizing for Chainsaw Al, just the harsh dismissiveness of mean business. Unfortunately, arrogantly chainsawing through workplace difficulties only creates confusion and suffering. The Mahakala method warns us against taking such a sloppy and impulsive approach to resolving conflict. We now know that Chainsaw Al drove firms like Sunbeam and Scott Paper into the ground by setting unachievable goals, inflating stock prices, and ultimately misstating the financials. His style of mean business created nothing but confusion: dozens of lawsuits, criminal investigations, and thousands of unemployed.

Being firm and direct when making tough decisions need not be so sloppy and degrading. Because we are willing to listen and compromise, because we are willing to consider options and appreciate others, we can confidently turn down a job offer, challenge a colleague’s rude remarks, or simply say, “The price is just too high.”

The Four Actions of the Mahakala method teach us that if our state of mind is not threatened by workplace conflicts, we can take a fresh look at confrontations and be generous in spirit and intention. We can afford to drop our defensiveness and listen to our colleagues; we can afford to be imaginative and open. If we slow down and drop our resistance to work’s unpleasantness, we discover that we are resourceful enough to be daring, free from fear and arrogance. Such confidence enables us to know instinctively which situations need to be confronted, which should be nourished, and which can be disregarded. Mahakala reminds us to sharpen up during times of conflict, to be mindful and pay attention. With such alertness we can in fact preserve the sanity of our workplace even during extreme discord. We need not fight the energy of conflict. We can practice the four actions of the Mahakala method and embrace our jobs precisely and authentically.