Jeff Bridges enters the living room of his hotel suite carrying a dark blue Shambhala paperback by Chögyam Trungpa entitled Training the Mind and Cultivating Loving-kindness. “One reason I’m anxious—because I have some anxiety about this interview, like you do,” he says, as he arranges his long body on the couch, “is that I wish I could be more facile with these things that I find so interesting and care about and want to express to people.” He opens the book. “This will be a challenge for me,” he says. “But I’ll attempt it.”

Bridges is 61. Solidly built, he reminds me of an Andalusian carriage horse in late prime, trustworthy and sensitive. He is wearing jeans, clogs, a chambray shirt, and the Rolex Submariner watch that his late father, Lloyd Bridges, wore on the television series Sea Hunt. Were it not for his lightly mussed hair and that expensive watch, he could be a motorcycle mechanic.

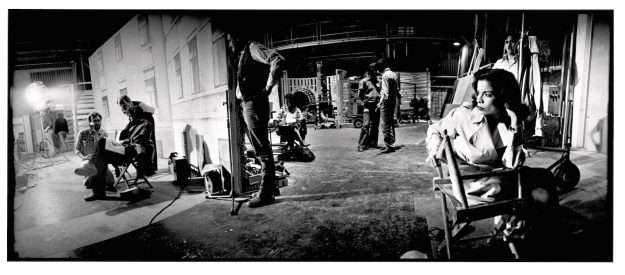

We’re talking in Austin, Texas, where he’s filming a violent, darkly comic version of the Western True Grit—the first “period Oater” (as Variety put it) to be directed by the filmmakers Ethan and Joel Coen. In it, Bridges plays Rooster Cogburn, an aging U.S. Marshal who has, not surprisingly, a drinking problem. Like the washed-up country singer of Crazy Heart, the self-betraying lounge pianist of The Fabulous Baker Boys, and the reluctant ex-convict father of American Heart, Cogburn is one of a string of beautiful losers Bridges has portrayed teetering on the brink of some sort of redemption. His acting is so naturalistic and seemingly effortless, in fact, that you can forget that it’s acting.

But anyone who mistakes Bridges for the beatific, potsmoking, Zenlike Dude of The Big Lebowski misses much of what quickens beneath the surface. He was born in 1949 in Los Angeles into an unusually stable movie family, to a loving mother made panicky by the recent loss of an earlier son to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Anxious enough to stutter as a child, he still struggles with what his mother, Dorothy (who also practiced meditation seriously before her death last year), called abulia: difficulty committing to a path of action. He’s been married for 33 years, has acted in 66 films, and helps fund the End Hunger Network of Los Angeles, dedicated to ending the hunger suffered by 16.7 million American children. On its website, he is quoted as saying, “If we discovered that another country was doing this to our children, we would declare war.”

In his hotel bedroom are his meditation bell (a travel-sized gong timer) and a stack of Buddhist books, including Thich Nhat Hanh’s Walking Meditation and three by Pema Chödrön. Most days, before heading out to the film set he meditates for half an hour: following his breath, noticing his thoughts, sitting in a chair with his spine straight and his hands resting lightly on his knees.

Right now he’s intently focused on the blue paperback he holds in his hand: Trungpa’s interpretation of the lojong [mindtraining] teachings—59 slogans distilled by the 12th-century Tibetan master Geshe Chekawa from the writings of Atisha, a 10th-century Indian Buddhist teacher. They are pithy guideposts along the Mahayana path: “Transform all mishaps into the path of Bodhi,” “Regard all dharmas as dreams,” “Be grateful to everyone,” “Don’t seek others’ pain as the limbs of your own happiness,” and “Always maintain a joyful mind.” Throughout our interview he keeps threading back to these slogans, some simple and others arcane. “The basic idea,” he says, as he opens Trungpa’s book, “is that the things that come up, that we’ve labeled negatively—those are real opportunities and gifts for us to wake up.”

Turning pages, Bridges begins, “I just saw the word joy, and I see it’s underlined twice, and I got a star beside it, so let me read this aloud and see if it’s interesting. “As you are dozing off, think of strong determination, that as soon as you wake up in the morning you are going to maintain your practice with continual exertion, which means joy.” We were talking earlier about anxiety, excitement. That’s an exertion of sorts. But you can have that same exertion, but have this joyful attitude. Like I can study my lines for the day because I’m anxious about it, or I can just have fun studying lines. This word joy—another one of the slogans is “Approach all situations with a joyful mind”—I find in my practice joy is a big part of it. My parents were very joyful people. Whenever my father came onto a set to play a part, you got the sense that he really enjoyed being there, and this was going to be a good time. And everyone was just—[raises his arms] raised! When you relax like that, you’re not trying to force your thing onto the thing. You’re just diggin’ it. My mother was the same way. That’s what I aspire to.”

So there’s joy on the one hand—and you mentioned negative things, as an opportunity to wake up. Is this playing out in your acting in True Grit? [Long pause.] It’s difficult to talk about the work, because it’s like a magician talking about how the trick is done.

How about your character, then, the drunken, overweight U.S. Marshal who teams up with a 14-year-old girl to track down her father’s killer? I don’t know if it has anything to do with the lojong thing, but most things do, in a weird way. A bunch of things are popping in my mind. [Pause.] “True grit” means that you’re courageous. The habitual tendency when things get tough is that we protect ourselves, we get hard, we get rigid—[makes a chopping gesture]—Bapbapbapbap. But with this lojong idea, it’s completely topsy-turvy. When we want to get hard and stiff and adamant, that’s the time to soften and see how we might play or dance with the situation. Then everything is workable. In True Grit, my character—all the characters— are that way.

As an actor, fear comes up because I want to do a good job, an enlightened piece of work. You get attached to that, you overwork it, you overthink it. Then you come to the set, and people aren’t saying the lines as you imagined. It’s raining, and its supposed to be sunny. You thought you were invited to a cha-cha party, you’ve learned the steps, and they’re dancing the Viennese waltz! You can spend a lot of energy being upset, or you can get with the program—it’s that right effort thing—get the beauty of the way it is. Even before I was aware of lojong, this was something I applied to my life anyway.

Do you think of yourself as a Buddhist? A Buddhistly bent guy sounds kind of right. I haven’t taken the refuge vows.

Why not? I’m quite a lazy fellow.

You’ve been in 66 movies. You paint, you take professional-quality photographs, you use the power of celebrity to end hunger. You’re still married, and you play guitar and singwell enough to carry a CD of songs from Crazy Heart. I wonder if you’re selling yourself short. One of the lojong slogans comes to mind: “Of the two witnesses, hold to the principal one.”

Huh? Always hold true to your own perception. Your own self is your main teacher. I have a lot of different feelings about my laziness. Sometimes I enjoy it, kind of like the Dude.

Does it irritate you when people confuse you with the Dude? Oh God no. There’s a lot of stuff where we don’t match up and a lot where we do. I admire the Dude. He’s very true to himself, whereas I can get my hair shirt on and beat myself with my whips and say, Why can’t you take more interest in others?

You’ve been meditating for ten years, and you’re close friends with Lama Dawa Tarchin Phillips, a Kagyü teacher in Santa Barbara, and with Roshi Bernie Glassman, with whom you share an interest in alleviating hunger. But I still don’t get how you got started with Buddhism. There’s not really a hard edge to it. I’m just curious about all kinds of spirituality. Bernie’s given me some tips on meditation—he’s like a spiritual friend. I don’t have a formal teacher. Everybody I come in contact with is my teacher. Other actors are certainly my teachers. One of the cool things about acting is to realize how accessible love is. You can invest a person, another actor, as your love. I’m familiar with that feeling—I have this tight, strong relationship with my own wife. One of the reasons I’ve been married so long is that she has encouraged my art and my intimacy with other people. It’s important it’s not sexual—that can throw a wrench into the works. But when you get two people [on a set] opening their hearts to each other, that feeling of compassion and understanding is really accessible and quite deep. And the flip side is also true, of fear.

In the 1980s, I was a kind of a guinea pig for John Lilly, who invented the isolation tank. You sit in this tank of water at 98.6 degrees, you have no sensory input, and your mind produces all this output. It started very softly. Oh, this is kind of interesting [Takes on a California New Age singsong voice] and John seemed like a nice guy. And then, He was wearing a weird jumpsuit. Did he have…breasts? I let my mind run on that. Fear came—whoosh!—roaring into my body.

That’s the idea of shenpa [attachment or craving]: running, running and pretty soon that fear is hard as rock! That’s the kind of thing you do in acting, consciously, all the time. Now, where were we?

The isolation tank. Oh, yeah. I went, Wait a minute! That’s my mind! Instead of jumping out I made a little adjustment. I noticed I could breathe in and out slowly and observe my breath and not be in control of it. It was my first experience with meditation, although I didn’t call it that.

I have a lot of Christian input, too. You’ve got to read this guy [Nikos] Kazantzakis [author of The Last Temptation of Christ]. His whole thing was that Christ was just like us. And God was like an eagle with talons, coming into his head [Picks up his own hair], trying to pull him off the ground. Just like I have so much resistance to this Buddhist stuff. I’m attracted, but I’m a human being, I’m attached to myself, and I kind of dig it. You know?

Oh, yeah. This hunger thing, for instance. I mean, it’s not like it’s…

Not like it’s fun? Well, it can be fun. It’s a mindset. Werner [Erhard, founder of est training and one of the founders of the Hunger Project] said, “Here we have this condition that doesn’t have to be that way. We can end it.” I said to myself, Yeah, that seems right. And I noticed I had a resistance [to committing to do something], because I wanted to do other things with my time besides help people. So I said, Well, maybe let both of those things exist at the same time.

It’s like this. Preparing for a role, sometimes I’ll have to get in shape fast, lose a lot of weight. But I don’t want to work out so hard the first couple of days that I’m sore and I don’t like it. I thought I would apply the same thing to this hunger work. I would go toward the light, so to speak, but if it got too bright and too intense, ’cause basically what it’s asking you is Be Jesus, be Buddha—Give. And I’m not there. I’m not light yet. [Changes to another, higher voice.] So just because you’re not there yet, are you not going to do it?[Cocks his head.] So I go toward the light, and if my selfishness comes up too much I’ll stop for a second. And then I’ll take little baby steps toward it. I like to experiment with myself, to go against habitual self-gratification. And then you try it and you say [high voice], Oh, hey, I kind of got off when I did that. That kind of felt good! It’s like taking a shit. Sometimes it’s best to just pick up a magazine and get in there and sit, rather than Aaaaargh [mock straining]. It’ll kink up that way. Or when I’m doing yoga, I’ll go Put your head on your knees, you son of a bitch, come on, oh you can’t do it, oh you’re—

Uh-huh. Instead of just being gentle, kind. [Breathes out.] Aaaah. That grandmotherly attitude. Show up. Bear witness. And then the lovingkindness comes naturally.

Did anything change when you first started to formally meditate? I did. And my wife noticed, too. Just kind of a calmness, not so stressed out. And I’m wondering if this lojong theme, which I’m kind of getting into now, has really been going on all my life. That the very things you avoid, those are the blessings. It might even be a thread in the characters I’ve played. One in particular comes to mind, American Heart. I don’t know if you saw that.

It broke my heart. The 1992 film you starred in and helped produce—inspired by Martin Bell’s documentary Streetwise and Mary Ellen Mark’s photographs of homeless Seattle kids. In the [Bell] documentary, a kid visits his dad in prison. The way he expresses love for his kid is to say, in so many words, “Don’t end up like me.” Well, that kid ended up hanging himself in a bathroom. There’s a scene of his father getting out of prison and looking at his kid in the casket and putting a Coke can to his [son’s] lips. I thought, What if that guy got out of prison and had to work with his kid? So you remember the scene in American Heart, where [my character] just gets out of prison, he’s in the bus station bathroom trying to get on his clothes, and here comes his kid. And he’s like, Oh, shit. Just what I need, I can’t deal with you. I’ll be lucky if I can survive myself. And it turns out that his kid was a blessing, the key to his life. The thing he was avoiding—you can apply this to the hunger thing we were talking about.

It occurs to me that making a movie is like making a Tibetan mandala of colored sand—you create a whole world on set, and then someone yells “Cut!” and the whole illusory world disappears. Movies are a wonderful spiritual playground. The film you actually make is like a beautiful snakeskin that you find on the ground and make a hatband out of. But the making of the movie is the snake itself. That is what I take with me. That includes hanging out with the other actors in the trailer after work, and getting into this position where you’ve empowered another actor to have a power over you, to affect you. That’s a spiritual place to be.

Crazy Heart, for instance, is a gorgeous snakeskin. But the snake of the thing was playing all of that wonderful music by Steven [Bruton] and T Bone [Burnett.] And the director, Scott [Cooper], did it in 24 days! The atmosphere he created—so open, so fresh and joyful. It was really a blessing in my life. That’s what you gamble for, and most of the time the movie falls short. And sometimes those high hopes are transcended, and it’s beyond what everyone thought it could be.

Making a movie is just a wonderful analogy for how the world might look. A movie’s like a child—if all the parents are doing their job, the movie is going to come out beautiful. That’s one of the ways that the world might be realized, working together. One of the reasons we decided to focus on children at the End Hunger Network is that the condition of the health of our children is a wonderful compass for how our society is functioning. Even as a little kid, I thought, Why can’t we get together and make it a groovy trip for everyone? There’s that concern with the self, the tightening, which seems to be preventing that.

Does being famous make it difficult for you to be in a sangha? I think of the sangha as a very soft, open thing. I’ve got people I’ve practiced with in a deep way for many years, like my wife, and my dear friends. Right now you’re in my sangha. We’ve touched in that way. Everyone I meet is in my sangha. I don’t know if that’s the proper definition, but that’s the way I’m going to hold it in my mind.

Final words for us? My mom used to say it to me, and my wife says it now. There’s even a slogan that says it! “Approach all situations with a joyful mind.” When I head out the door to go to work, my wife always says to me [Voice affectionate, up half an octave], “Now, remember! Have fun!”