I knowed I was in for a heap of sivilizing soon as I got back to St. Petersburg. But this time around it warn’t like no sivilizing I’d ever heard tell of before. First off, they had me go back and stay with the Widow Douglas, as she was all so lonesome ever since her sister, Miss Watson, passed away. Soon as I set foot in the house, though, I knowed something was up. She had that look in her eye that meant one of two things: either she was trying to pass a gallstone something fierce, or she had got religion of a sudden. Knowing her, I figured it was religion, so I laid low and minded my table manners good, so she wouldn’t take her religion out on me. But one day I said something mean about one of the neighbors, and so she heaved a big sigh and said, “You know, Huckleberry, the Good Book tells us that you should love thy neighbor as thy self, and my gooroo told me that that’s because thy neighbor is thyself, so every time you say something hurtful about your neighbor, you’re hurting yourself, too.”

This was the first time I had heard any such stuff, so I asked her what her gooroo was.

Well, I shouldn’t a opened my mouth, ’cause she set full steam to a bodacious sermon about what a fine Christian man her gooroo was, and how he brung the true religion back from Asia, and how we was all inner connected like, so that if we was to feed someone else, we’d get full, too, and if we was to steal our neighbor’s money, we’d be stealing from ourself. I let her go on, ’cause like I said, sudden religion is like a gallstone, and you just gotta letit pass.

Still, it began to weigh on me when she commenced in on me everyday, saying that—since we was all inner connected—I had to be responsible for the whole human race. I have hard enough a time trying to be responsible for what I do! But she kept after me like this till I couldn’t take no more, so finally I up and said, “If I gotta be responsible for them, who’s they gonna be responsible for? And if we’s all inner connected, how come when I put food in my stomach it doesn’t all spread out and connect to theirs? How come it has to go into their stomachs first ’fore it comes back to mine? It don’t seem fair. And if we’s all the same self, how come you let your slaves wait on you all the time? Why don’t you wait on them some, too?”

The minute I said that, I knowed I’d gone too far. The old widow she just busted out sobbing about what a mean boy I was, and how could I say anything so ungrateful to her after all she had done for me? I knew she was right, it was an awful low-down mean thing to say, so I tried to make up. “I’m sorry, ma’am. Sometimes I don’t know what gets into me. I’ll do anything to make it up to you.” But still it was kind a heavy in the house for a couple a days.

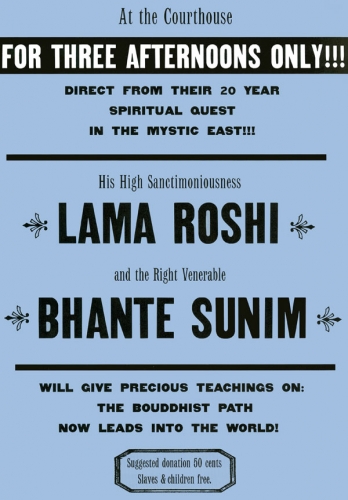

Then the widow got word that her gooroo was coming back to town to give a three-day teaching, so she lightened up considerable and got to humming to herself like an angel half-full of cream pie. By and by she said to me that if I really did want to make up for the mean thing I’d said, I’d go and listen to the teaching along with her. Lawsy, warn’t I in a fix? I started seeing bills for the gooroo posted around town a few days before his arrival. His name was Lama Roshi, and the bill went like this:

I asked Tom Sawyer to go along with me, since I didn’t think nobody in town but me and the Widow Douglas was going to show up at the teachings. But was I ever wrong! The courthouse was packed. And I’m lucky it was, ’cause otherwise Lama Roshi would a spotted me in the back row. I say I was lucky ’cause Lama Roshi warn’t nobody else but that old rapscallion, the king, only this time he had his head shaved and sat himself up in a high seat all wrapped up in this big black robe looking holy and fearsome as ol’ Moses himself.

Well, when the crowd settled in, he started out chanting low and mournful and would a raised the spirits out of the cemetery if it’d been midnight. It gave me the fantods just to hear it. Then he made an announcement that Bhante Sunim had some pressing ’gagements back East and so warn’t able to attend this special teaching but sent his personal blessings to everybody there. It didn’t take too much hard thinking to figure out that Bhante Sunim was the duke, and that he’d got himself into some trouble down river and so couldn’t show his face till it had all blowed over.

At any rate, the king started talking about all the many years he’d wandered around Asia seeking true religion and sitting in Zen monasteries where all the monks sat in a row with their legs tied up in knots, except for the chief monk who walked up and down with a big stick he’d use to whack you upside the head without no warnin’; then gettin’ sealed into a cave for months and months in the frozen Himalayas without no food or water, so’s you had to depend on angels to feed you and keep you warm and so on. I knew it was all a passel of lies, ’cause I had seen the duke and the king tarred and feathered down south just a few months before, but my souls, it sure did make a fine tale!

Then the king started giving the teachings he had learnt on his quest, and my, did he ever spread himself out! And with such style! It was such a rattling good talk that even a perfessor couldn’t a understood a half of it! The only part I could catch was that there was two kinds of people in this world, Hyenayanists and Mohayanists. The Hyenayanists was a bunch of lowdown, good-for-nothing deadbeats only looking out for their own skin, while the Mohayanists was the finest, most up-standingest Christian folk you might ever hope to meet. The king he said that after all his years of suffering on the spiritual path, he realized that the Asians made it so hard ’cause they warn’t nothing but a bunch a heathens, and so had to have ’lightenment walloped into their heads. But we here in America—especially the good folks here in this fair town of St. Petersburg—had a head start on them on account of our fine, sivilized Christian upbringing, so all we needed was to hear his teachings for a few more sessions and we’d get ’lightened, too.

Well, you can imagine what a rousing reception everybody gave to a talk like that! The Widow Douglas she had tears in her eyes. Somebody said the Lama’s fine missionary work deserved more than just fifty cents a head, so they started passing the hat—only they called it the Donna basket—and took in upwards of another fifty dollars. At first the king refused to accept it, saying that it was his honored privilege to be teaching such good-hearted folks, but finally they pressed him enough so he couldn’t say no. Then somebody else up and asked where he was going to spend the night, and the king said he’d found himself an abandoned old shanty just outside of town that was perfect for a simple monk like him to meddle-tate in. Well, the Widow Douglas she pipes up, saying she wouldn’t see her gooroo sleeping out in a place like that when she had a guest bedroom just a-begging for his holy presence. So everybody volunteered to get the king’s bags from the shanty and fetch them up to the widow’s place.

The king he looked like he was in a spot when he heard that, but then he recovered enough to thank them kindly, saying he’d have to pack the bags himself ’cause he had all kinds of sacred texts that had to be wrapped up just right. Well, when I heard that, I would a bet a di’mond palace full of chewing gum that his “sacred texts” was his jug, and he didn’t want nobody to catch sight of it.

That evening, while the king was setting in the parlor with the widow, talking high and pious about inner connectedness, Tom come shimmying through my window, and we snuck into the guest bedroom. It warn’t too long before we found the jug stashed in the closet. While we was setting there a-figuring, we heard a noise coming up the stairway, so we shut ourselves into the closet with the jug and held our breath tight.

Well, it was the king himself coming into the room. He lit a lamp and started counting the money, all the while chuckling quiet like. It warn’t long, though, before there was a tap-tap-tap at the window, and then there was the sound of somebody dragging himself into the room, and then the voice of the duke.

“How’d we make out today, your Sanctimoniousness?”

“Fine. Jest fine, ven’rable sir,” the king said. “Just look at this-yer haul we got this afternoon! And this bein’ jest the first day! What a bunch of rubes!” The duke he sounded mighty happy himself, so the king said, “I say this calls for a little celebration, don’t you, Venerable? I’ll go get the jug.”

Tom and I knew that there warn’t no way the king wouldn’t see us if he was to open the closet door, so we did the only thing we could do. Even before the king got to the door, we opened it up from the inside and jumped out, staring him straight in the eye. The king went stark white, seeing as we had found him out, but the duke he was quicker’n a cat cornered in a pantry. “Well, I see you boys passed the test,” he said, with a sudden big smile on his face.

There was dead silence in the room, and then Tom asked, “What test?”

“Why, the test we set to see who were the smartest and bravest people in this town. We acted suspicious on purpose to see if there was anybody around here smart enough to have suspicions and want to check up on us. And only the bravest and quick-wittedest boys in the state of Missouri would have jumped out of the closet the way you did just now, ’stead of just cowering there. So it looks like you two are the only ones with head and heart enough to deserve a direct transmission of our secret teachings. But only on the condition that you swear the direst oath to secrecy. Are you boys man enough for that?”

Well, there warn’t nobody like Tom Sawyer who was such a corn-meal muffin for buttering up, especially when they was oaths and secrets involved. “What kind of oath?” he asked. So the king started reciting the oath, saying that we’d have to vow not to bad-mouth womenfolks and not snitch on our gooroos and not go consnortin’ with Hyenayanists or else we’d be willin’ to die the most horriblest death and have jackals tear our bodies into a million bits while we plunked down to the lowest hell to eat nothin’ but molten iron for aeons if we ever so much as thought of retractin’ our oath, to say nothin’ of what would happen if we actually disobeyed it, cross our hearts and hope to die three million different blood-curdlin’ deaths.

Tom and I agreed that it was a powerful fine oath, and it made a body tingle just to think about it. He was all for taking it right away, and I couldn’t think of no way to stall him, so even though I didn’t trust the king and duke no further than I could a tossed a dead cow, we both took the oath right then and there. I kept my fingers crossed on the sly, though, just in case, and I’m glad I did, or I wouldn’t a lived to write this stuff down.

Once we had swored our oath, the king sat us down and said, “All right, boys. The first secret Bouddhist teaching is that there ain’t no such thing as good ’n’ evil.”

“Wait a minute,” Tom said. “I got a book on Bouddhism out of the library this morning, and it said that the Bouddhist teaching was to do no evil, to develop skillfulness, and to clean out the mind.”

“That’s right, boy. That’s right. But that’s Asian Bouddhism. We’s talking about American Bouddhism. The principles is diffrent.”

“But the book said that that was the Dharma, and the Dharma is truth. Ain’t the truth the same everywheres?”

The king just put his left hand up in the air. “It all depends on your pint of view. Looky here. Which side of the room is my hand in?”

“The north side,” I answered.

“Now you hush up, Huckleberry. You don’t have ’nuff schoolin’ to know how to answer these-yer questions. You’s supposed to say it’s in the right side of the room.”

“All right,” I said. “It’s in the right side of the room.”

“But from my pint of view, it’s in the left side, see? See how much diffrence there is ’tween us when we look at things from diffrent sides of the room? Now them ther’ Asians, they’s on the diffrent side of the world. Why, when the sun’s going down here, it’s going up there. So the truth over there and the truth over here is bound to be two diffrent things.”

The duke started in then, saying that in Asia the truth was what some old monk told you, but over here the truth is what sells. “If people don’t buy it,” he said, “it ain’t true. That’s why we have democracy and a jury system. Over there in Asia, the students have to say what the teacher wants to hear, but here in America, the teacher has to say what the students want to hear.”

“Yep, the truth is whatever sells,” said the king. “And ain’t nothing sells like tellin’ people that what they’s already doin’ is jest fine. Why d’you think we keep tellin’ ’em that the Bouddha’s path, now that it’s come here to America, heads back into the world?”

“I—I don’t know,” Tom answered. “Does it mean they’re already just right like they are?”

“My, you do catch on fast, don’t you, boy?” said the king. “That’s jest percisely what it means. Fer do-gooder types like the old Widow Douglas, bless ’er soul, it means they kin keep runnin’ ’round tryin’ to be helpful and sens’tive to the feelin’s of others, and feel mighty righteous about it meantimes. As fer the rest of us, it means we kin jest go ahead and have ourselves a good time, ’cause the do-gooders will look after us, and there ain’t no world better’n this.”

“That’s the secret meaning of the teaching on skillfulness and cleanin’ out the mind,” the duke chimed in. “Evil ain’t evil if you do it up skillful enough. Just keep your mind in the present and don’t let it think about the past or future. You’ve got to clean out your mind till it’s no-mind. Then you don’t have to remember what you done in the past nor worry about the future, so there’s no remorse or contrition or sin.”

Then the king took a long breath. “Well, I reckon that’s ’nuff secret teachin’s fer you two younguns tonight. I bet your brains is jest spinnin’. Why don’t you jest head on down to bed, now? The duke and me, we need to get in some serious time on our skillful drinkin’ practice ’fore we hit the hay.”

So Tom and I said good night and went back to my room. When we got there, I asked him,

“Well, what do you think, Tom Sawyer?”

“What do you think, Huck Finn?”

I thought a spell and said, “What I think is that some things may be right and left, like the king says, but there’s a plenty a things that’re north and south. I don’t wanta have nothing to do with that king and his truck.”

But Tom he got a funny look in his eyes and said, “I don’t know, Huck. I think you’re missing something here. What the king says has got lots of possibilities.”

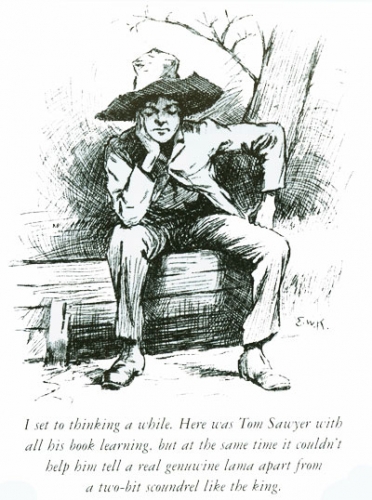

He started getting lost in his thoughts, and I didn’t feel too comfortable about what he had said, so we didn’t talk too much after that. By and by he said good night and slid out the window. I set to thinking a while. Here was Tom Sawyer with all his book learning, and you had to give a body credit for that, but at the same time it couldn’t help him tell a real genuwine lama apart from a two-bit scoundrel like the king. In fact, it even got in the way of him seeing that the king was up to no good. If that was the case, I reckoned, I didn’t want to have no more to do with book learning or these town people and their sivilizing. So don’t be surprised if you don’t see me ’round here no more. It means I’ve lit out for Injun territory. Maybe the folks out there will make more sense.

Yours truly, Huck Finn ▼