Theravadin monks in Stockton, California, open their temple to the streetwise youth of the local Southeast Asian community, and offer a haven from gang-ruled neighborhoods. Now the monks stand accused of violating their monastic vows by engaging in worldly affairs.

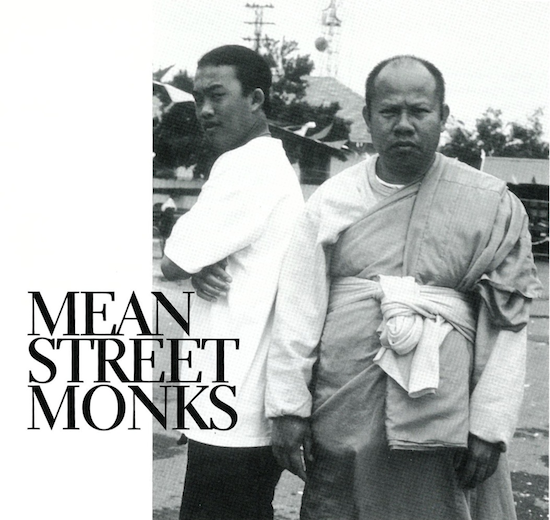

Abbot Sombun Athitano stands on the balcony of Wat Chansisamakidham and looks out over the parking lot. With his arms akimbo and his expression deeply serious, he resembles a mythic hero keeping a vigilant watch over his protectorate.

He is remarkably calm for a man accused of heresy. His confident stance and his unshakeable poise make it impossible to tell that he is the central figure in a controversy that has divided his temple’s constituency and threatens to destroy his life’s work. From his position on the balcony, he surveys his domain with tactical scrutiny. In the near distance, he sees downtown Stockton, one of northern California’s most notoriously blighted urban neighborhoods. Junkies roam South Hunter Street desperately seeking a fix, while drunken men and women lay unconscious on the sidewalks. Every window is behind bars, and every accessible vertical surface is marked with gang graffiti.

It’s hard to imagine why a Theravada monk from rural Thailand would establish a temple in a place like this. But as Abbot Sombun shifts his gaze to the foreground, he receives a vivid reminder of the purpose behind his mission.

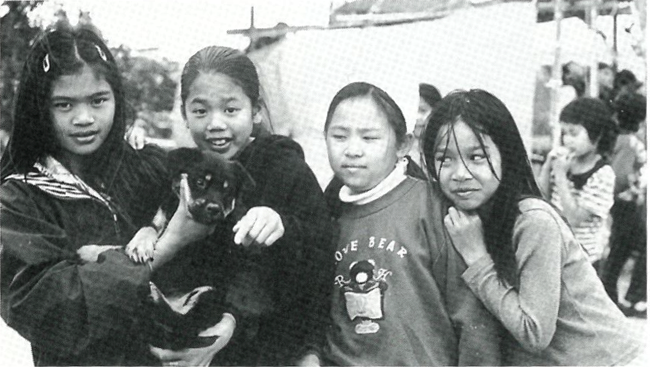

The temple parking lot is teeming with kids. The younger ones are playing in a sandpile, while a group of older girls blasts the sounds of a Laotian pop group through a portable stereo. They range in age from two years to late adolescence. Most are Laotian-American, though some are of Thai, Hmong, or Cambodian descent. They come to the temple to worship and play, but mostly they come for a much-needed refuge from the violence of the streets.

“We established this temple with the kids in mind,” explains Abbot Sombun. “There are all kinds of dangers in this neighborhood—guns, drugs, gangs. By keeping them off the streets, we’re keeping them from harm.”

But not everyone agrees with the abbot’s methods. On May 16, 1999, a group of protestors—all former members of the abbot’s constituency—stormed the temple and demanded a change of leadership. Abbot Sombun, they claimed, had become too familiar with the ways of the world. In his efforts to reach out to the children of his neighborhood, he and his fellow monks had violated the time-honored codes of monastic non-attachment. Monks should be ritual practitioners and models of quiet reflection, say the abbot’s accusers, not referees and guardians to a temple full of streetwise kids.

The Gangs

There are more Southeast Asian gangs per capita in Stockton than in any other city in the United States. They have names like Cambodian Mob Family, True Laos Crips, Eternal Wat Tribe, and Cambodians With Attitude. Some are local affiliates of larger “gang nations,” such as the Bloods and the Crips, while others are strictly independent. Their exploits range in severity from substance abuse and “tagging” (graffiti vandalism) to drive-by shootings and gang warfare. But they are most renowned for their violent home invasions.

Because many older Cambodians and Laotians grew to distrust public institutions during the wars in Southeast Asia, they now keep their cash savings at home rather than in banks. Southeast Asian gangs are well known for conducting paramilitary raids against such people and stripping them of their lifetime’s savings in less than two minutes.

To those who rigidly associate Buddhism with non-violence, it may seem strange that Buddhist children are joining violent street gangs in ever-increasing numbers. But the appeal of the “thug life” to the kids of downtown Stockton is undeniable. Gangs offer economically disadvantaged young people opportunities to earn more prestige and more income than they are likely to find in other sectors of the American economy.

Gangs also offer kids a distinct sense of identity. The young people of Abbot Sombun’s neighborhood are precariously situated between the Southeast Asian culture of their parents and the American culture of their schools and streets. Most claim to fit comfortably in neither, and many—the ones who never learn about Wat Chansisamakidham—see the gangs as the only social organizations in which both converge harmoniously.

If Stockton’s Southeast Asian gangs exhibit no other admirable traits, they are at least eclectic—especially when it comes to synthesizing otherwise incompatible strains of ethnicity. For example, most Southeast Asian gang members see no contradiction between traditional Buddhism and American gang violence. It is not unusual to see them simultaneously wearing Buddhist amulets and packing handguns. They sport Buddhist tattoos, visit Buddhist temples on festival days, and consider themselves to be genuinely Buddhist in every way.

This is not to say, however, that they are particularly well informed in matters of Buddhist doctrine. If they were, says Abbot Sombun, they wouldn’t be in gangs.

“The way of the gangs is violence,” he states, uncompromisingly. “The way of the Buddha is peace.”

The Hood

Stockton, California, is a city of a quarter million people located forty miles southeast of San Francisco. Its downtown area mixes Mexican-, African-, and Southeast Asian-American communities. Wat Chansisamakidham occupies a block that is inhabited mainly by Laotian, Hmong, and Cambodian refugees who came to the United States following the genocides, wars, and economic disasters that plagued their native lands during the 1970s and 80s.

There are twenty-four known Southeast Asian gangs in Stockton and its environs. Rivalries between them are so intense that even Buddhist temples sometimes become sites of violent territorial disputes. While Wat Chansisamakidham has so far managed to stay out of the crossfire, other local temples have not been so fortunate.

“My Uncle Kyle got jumped by a gang at a temple over on the South Side,” reports twelve-year-old Bay Kammanh, who spends much of his spare time at Wat Chansisamakidham. “It was during a festival, so there was a lot of people there. He got up to go to the bathroom, and some gang guys asked him where he was from. He told �em Lewis Park, and they took a knife and tore his leg up.”

Incidents like this are startlingly common for Stockton’s Buddhist temples. In 1999 police evacuated one nearby temple because of a gang-related gunfight. And on April 16 of this year three people were shot to death at another temple when members of two rival gangs opened fire on one another.

Yet despite such incidents, the youth of Wat Chansisamakidham describe their own temple as a bastion of safety. They say it’s an exception to the rule of gang violence.

“Other temples always have fights,” declares Thea Kammanh, Bay’s seventeen-year-old sister. “But this one never had any fights or anything like that. Because it’s like, even though sometimes the gangstas do come [to the festivals], they really respect this temple. So I never seen them have any fights.”

“It’s sort of a safe haven,” says Christopher Lewis, a reporter for the Stockton Record. “It’s almost like there’s an imaginary border around here that’s for protection. And the kids know they’re okay when they come in here.”

The Monks and Their Mission

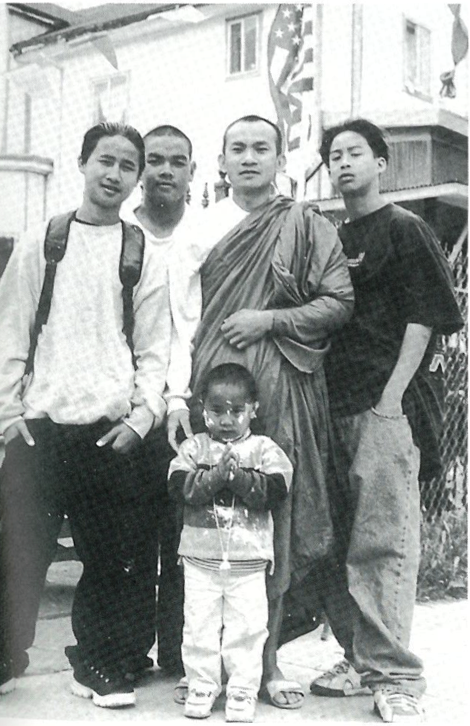

Wat Chansisamakidham was founded under the direction of Abbot Sombun in 1991. It is the regular gathering place for dozens of local youth. Some visit sporadically, but others are there every day. And a few—mostly older boys who come from large families with limited sleeping space—are there every night.

Many of the kids describe the temple as “a big family,” and their analogy is apt in a number of ways. The building itself is a house, a decrepit Victorian mansion that the monks have striven diligently to refurbish over the years. Abbot Sombun is its master. He requires the kids to do their chores—to cook and clean for themselves and one another. The older kids look after the little ones, and those who can drive run errands for the rest. The kids of this temple are unmistakably streetwise. They dress in hip-hop clothing and speak the language of gangsta rap. They all know gang members, and most say they’ve been pressured to join gangs on multiple occasions. A few, like twenty-year-old Lae Phimpa, are former gang members who attribute their reform to the intervention of the monks.

Surprisingly, the temple offers fairly little in terms of formal youth programs—beginning monastic training for boys and a summer school for children of both genders. Yet despite the relatively small number of specific activities for youth, it remains consistently popular with local kids. In fact, many of them claim the informality of the temple is the key to its success. They come not so much to participate in rigidly structured programs as to jump rope, shoot hoops, play hopscotch, and talk.

“I just come to kick it [hang out],” explains fifteen-year-old Khambei Vobouxasinh. “We feel safe here.”

Among the nine monks who reside permanently at the temple is Ajahn Keerati Chatkaew. He is renowned among the kids for his relentless sense of humor and his ability to imitate their street jargon. He came to the United States reluctantly in 1994, just after receiving his ordination from Buddhist University in Bangkok.

“I didn’t necessarily want to come here,” he explains, “but my master told me I was destined to play some part in bringing the Buddha’s teachings to the United States.” His master and others had insisted that America’s need for the dharma was dire. They told the young monk that America was riddled with crime, that violent youth gangs roamed the streets, and that even children of Buddhist descent were forsaking their traditional ways and turning to lives of violence, crime, and substance abuse.

“Frankly,” he admits, “I didn’t believe it. I thought they were exaggerating.”

By his own report, his first few years in California were marked by restlessness and a lack of purpose. He lived first at a temple in Richmond and then in Berkeley, never quite settling in either place. After a brief return to Thailand, he finally wound up at Wat Chansisamakidham.

“That’s when I found out they weren’t exaggerating,” he laughs. “It was all true—and even worse than they described it.”

Ajahn Keerati says his introduction to Stockton instantly changed his life. Not only did he suddenly realize the extent of America’s inner-city gang problem, he also found his sense of purpose.

“The kids here need the monks,” he explains. “Without this temple, they would have no place to play but the streets. They’d have no way to make positive friendships. And they might never learn the Buddha’s teachings.”

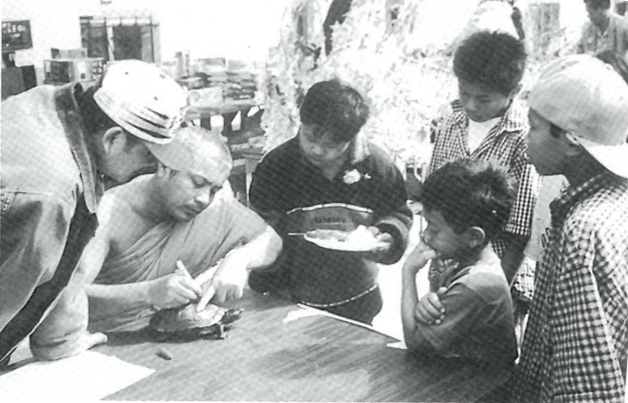

According to Ajahn Keerati, the mission of Wat Chansisamakidham is to give young locals a safe place to socialize and to teach them the traditional Buddhist virtues of non-violence and respect.

On the surface, this mission seems pretty simple. But in practice it has proven fairly complicated, because the monks of Wat Chansisamakidham maintain a delicate balance between the dictates of Theravada tradition and the extenuating circumstances of inner-city America.

The harsh realities of life in downtown Stockton have forced them to reevaluate the traditional modes of relation between monks and young people. According to Ajahn Keerati, the authoritarianism that typifies Southeast Asian pedagogy has only limited applications in the United States.

“We’ve gotta be tough,” he says, “but we can’t be too tough, or they’ll leave the temple and go to the gangs.”

The key to attracting local kids to the temple, he says, is a non-traditional teaching style that emphasizes explanation over punishment.

“All the monks are really friendly here,” says fourteen-year-old Patty Silasack. “In other temples, if you do something wrong, they hit you or yell at you. But here they take the time to explain to you why it was wrong.”

The youth of Wat Chansisamakidham unanimously declare unqualified approval of their mentors’ brand of engaged Buddhism. They claim the monks are exactly the type of active Buddhist role models they require in order to stay more interested in the dharma than in the dangerous thrills of the streets.

But critics in the community claim that Abbot Sombun and his peers have violated age-old rules that require monks to disassociate themselves from secular distractions—especially the frivolity of child’s play. The monks of Wat Chansisamakidham, they say, are not heroes but heretics.

The Controversy

It is hard to imagine, just by looking at him, that Abbot Sombun has been accused of reckless disregard for the rules of monastic non-attachment. He is a quiet man who interacts minimally with others and rarely ever smiles. The only evidence that he has a sense of humor is the dry wit he sometimes exhibits during his public addresses to the adults of his constituency. Otherwise, he creates the impression of an eminently stern individual. His expression is usually dour and his verbal communication is succinct and strictly pragmatic.

Yet his critics depict him as a shameless hedonist who has led his fellow monks—and their entire community—into spiritual ruin. They say that he has routinely violated the moral teachings of the Buddha and that his infractions have destroyed the integrity of the sangha.

“We’ll fight him forever, for generations,” said former temple board member Edward Sees in an interview for the Stockton Record, “because he destroyed our people, our religion.”

Opposition to the abbot’s leadership is often heated, and the charges leveled against him and his fellow monks border on fantastic. The wildest of them include drunkenness, gambling, gang affiliation, and watching pornography.

“That’s ridiculous,” says sixteen-year-old Johnny Kammanh in defense of the monks. “I’ve been here almost every day, and I never seen nothing like that.”

“Besides,” adds eleven-year-old Nancy Xayaseng, “those are exactly the things they’ve been teaching us to stay out of.”

At present, a group of approximately forty dissenters is taking legal action to remove the monks from the temple. However, the majority of the Chansisamakidham community continues to support the temple’s leadership.

The conflict between the monks’ opponents and their supporters is a contemporary version of the age-old struggle between religious conservatism and religious progressivism. The dissenting faction finds any variation from the traditions of Southeast Asia inexcusable, but the temple’s supporters feel that modest adaptation to American ways is both inevitable and desirable.

The dissenters are incensed that the monks drive cars, but supporters claim the logistics of urban America make occasional driving a necessity. The dissenters lament the fact that the monks of Wat Chansisamakidham do not strictly enforce the ancient rule requiring them to sit at a higher elevation than lay people. Supporters claim, however, that the occasional relaxation of this rule leads to an atmosphere of hospitality that can only be helpful in keeping Theravada alive in America.

Tensions between the two groups came to a head on May 16, 1999, when a group of approximately twelve dissenters entered the temple grounds and demanded that Abbot Sombun forfeit the property to them. He had made too many concessions to American culture, they claimed, and they would not leave the premises until their demands were met. The dissenters confronted the abbot and other monks in a manner that bystanders later described as physically threatening. Witnesses say some were wearing guns and one was carrying a baseball bat.

The older kids who were present at the time quickly phoned their friends, and within fifteen minutes more than twenty adolescents had gathered by the temple gate, ready to physically remove Abbot Sombun’s accusers. According to fifteen-year-old Ricky Lam, none of the adolescents were armed, because the monks had taught them to eschew violence.

“We didn’t want to fight anyone or get anybody hurt,” says Lam. “We just wanted to get those guys outa there and save the monks.” Meanwhile, the abbot was inside the temple facing his accusers. A fellow monk informed him that a large number of kids was outside plotting a rescue. Honored by their loyalty but concerned for their safety, he signed the temple over to the dissenters.

New Year’s Day

It’s New Year’s Day in Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand. The festival is called Songkran, and in Stockton it’s being celebrated on April 16, 2000—exactly six months to the day after Abbot Sombun and his fellow monks were to have vacated Wat Chansisamakidham.

According to the terms of the makeshift document the abbot signed under duress on May 16, 1999, he and his peers would forfeit the property on November 16 of the same year. But in the months following the showdown between Abbot Sombun and his accusers, temple supporters convinced him that he should not abandon his mission so easily. They suggested he take the matter up with a lawyer. The Abbot was reluctant to follow through on this suggestion but he met with members of the dissenting faction before the Council of Thai Bhikkus in America, the agency that regulates the activities of Thai monks throughout the United States. The Council, unwilling to take sides on the issue, concurred with the abbot’s advisors. The matter, they said, should be settled in court.

For now, the monks still live in Wat Chansisamakidham, but their stay is tenuous. The dissenting faction is still angry and still claims a moral right to the temple. They intend to acquire it by court order, disband it, and sell the property.

“It has a bad history,” explains Ajahn Chaiya Somboon, spiritual leader of the dissenting faction. His goal, he says, is to impeach Abbot Sombun and remove all evidence that Wat Chansisamakidham ever existed.

But today is New Year’s Day, and the atmosphere at the temple is festive. Songkran marks the end of a long period of hot, dry weather in Southeast Asia and the coming of the rains that will restore life to the land. It is a time for settling debts, renewing social bonds, and forgetting the struggles of the previous year. Many members of the community who stopped participating in temple functions after last year’s confrontation have returned to the temple today, and some vow to renew their commitment to it.

“I haven’t been here in a long time,” says Chanton Lam, smiling broadly. “But it feels good to be back, and I’ve promised the monks I’d get as involved as I used to be.” For now, the tensions between conservatism and progressivism are diminished, but the matter is far from resolved. The people of this community still have to decide what it means to be a Theravada Buddhist in inner-city America. Will the tradition be preserved best through rigid adherence to old-country customs? Or must it appeal to the needs of the next generation in order to survive? Do the monks best serve the youth as exemplars of stoic detachment? Or is radical engagement the best way for them to demonstrate the relevance of the dharma?

A feeling of goodwill pervades the festival as the kids douse each other with water balloons and super-sized squirt guns. Their play is an American variation of the traditional water play for which Songkran is famous. It symbolizes spiritual cleansing—washing away the bad karma of the old year and returning to a state of innocence for the new one. But as the festival draws to an end, news spreads among the celebrants that Songkran activities at a nearby temple have ended in tragedy. There, the kids used real guns instead of squirt guns, and three people were shot to death in a feud between gangs.

Now more than ever, the question of how to instill the dharma in the hearts of Stockton’s youth begs for an answer.