“Being a pioneer is not always the most wonderful thing,” says Jeff Waltcher, executive director of the Shambhala Mountain Center (SMC), in Feather Lakes, Colorado. He ought to know. As administrative head of one of the country’s largest Buddhist retreat centers, Waltcher has to juggle the headaches of budget, staffing, maintenance, and program development—not to mention making sure bears don’t eat any meditators and forest fires don’t burn down the stupa.

These are all part of daily life at this growing center, founded in 1971 in the mountains of northern Colorado. Not that Waltcher is one to complain: “Something about being in the middle of the country is powerful. Our environment is reflective of the wilderness of the mind.”

In what is still a relatively untamed part of America, practitioners have the chance to observe how weather, landscape, ecosystem—and mind—shift from moment to moment. In some ways, of course, this awareness comes easily to Buddhist practitioners. “The Buddhist view of working with the mind is fundamentally an ecological one,” Waltcher muses, reflecting on how the interrelated aspects of mind are observed and used in the process of awakening.

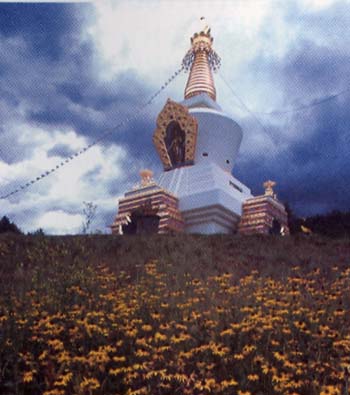

The facilities at Shambhala Mountain Center further reveal this integration of contemplative practice and the environment. The grounds include a native bird sanctuary and gardens for native plants, food, and Zen contemplation. The most prominent structure is the Great Stupa of Dharmakaya, which symbolizes the universe and the body of a Buddha. Rising to 108 feet, an auspicious number in Buddhist cosmology, the stupa contains relics of Chogyam Trungpa, founder of the Shambhala organization and one of the first Buddhist teachers to attract a large following in the West. The stupa also houses numerous pieces of Buddhist artwork. One of North America’s few Shinto shrines, dedicated to the sun goddess, can also be found at SMC. Other facilities include a lodge, several conference and study centers, campgrounds, dormitories, and a children’s center.

Following the Vajrayana tradition of turning obstacles into opportunities, the Shambhala Mountain Center has learned to take advantage of the challenges its rustic environment presents. To combat the omnipresent threat of forest fires, the center developed a local fire system that includes hydrants, a fire truck, and a volunteer fire brigade. The system has not only enabled the center to provide a needed service but has also evolved into an important bridge with the outside community, which has sometimes been suspicious of its Buddhist neighbors. Buddhism was an unfamiliar religion to most of the area’s inhabitants, and the Shambhala lineage has faced several controversies in the past. Nowadays, the center has become more accepted as a part of local life, and a nearby bar even offers discounts to thirsty Buddhists (the fifth precept notwithstanding).

SMC has found ways to extend its offerings beyond the Shambhala tradition, which focuses on Tibetan teachings; in fact, most program participants are not members of the Shambhala community. There are plenty of ways to apply dharma training to the outdoors when you’re situated on six hundred acres of mountainous terrain, and this melding of outdoor activity and Buddhist practice has proven key in attracting a variety of participants. In fact, only 60 percent of the retreats offered at SMC are touted as explicitly Buddhist. But even retreats that aren’t specifically Buddhist usually incorporate meditation into their schedule; recent examples include mindful gardening, mindful singing, even meditative mountain biking. Yoga, arts, and other activities are also included. Still, SMC provides the Buddhist mainstays: teachings and retreats from the Tibetan, Vipassana, and Zen traditions. This year, offerings have included Dzogchen teachings by Tsoknyi Rinpoche, lovingkindness meditation with Sharon Salzberg, and a Zen sesshin with Martin Mosko.

Another focal point of SMC is family dharma. “Making the teachings available to families is crucial,” Waltcher emphasizes. “How does Buddhism take root in a country if you don’t involve young people? They are the most dynamic, perhaps the most open, segment of our population.” Shambhala Mountain Center runs a program for the children of retreat participants and staff, and holds summer camp as well as a “family camp” at the center every year, typically attracting forty to fifty families. This concern for how Buddhism is passed on to the next generation is part of the greater Shambhala vision. As Waltcher says, “The idea of Shambhala is ‘enlightened society,’ or how to impact society in a positive way. In the future, SMC will be a model that society will turn to. It’s important that we have places that offer a real counterbalance to what we’re being told is important by Fox News.”

It is still this basic idea of a bastion of spiritual wisdom as a model for society that informs the activities of SMC. “We want to be a lighthouse for the tradition,” Waltcher says. The Tibetan myth of Shambhala speaks of an enlightened Buddhist kingdom in the mountains, preserving the dharma through difficult periods so that it can offer wisdom and awakening to the world when the time is right. For more than thirty years, through fire and ice and grizzly bear encounters, the folks at SMC have worked to establish such a place in America’s greatest mountain range.

For more information on SMC, visit http://www.shambhalamountain.org