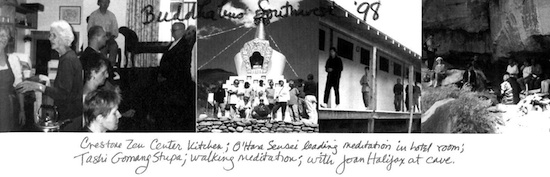

Recently, I visited New Mexico to join the first Buddhabus Tour. Organized by the Tricycle ExChange, a membership program for our readers, the trip included eighteen adventurers. They started off with a workshop at Naropa Institute in Boulder and, after a day’s ride through the Rockies, arrived in Crestone, Colorado, where they stayed at Richard Baker’s Zen center and visited the Tashi Gomang stupa. Then on to Taos and Santa Fe, where the travelers attended separate workshops with Joan Halifax, Natalie Goldberg, and vipassana instructor Marcia Rose.

By most accounts, the tour was a great “success,” although the terms of that success were not so obvious. Nine days on the Buddhabus had generated a profound vulnerability among the participants. By the time I joined the group, there was as much crying as laughter. These travelers had not signed up to vacate their minds amidst new scenery. Rather, they had come with real questions, some urgent; and once they had shared the intimacies of silence, their stories began to surface: the death of a husband; of a granddaughter; the terminal illness of a young spouse; battles with addiction; love lost and betrayed. Very common. Very painful.

The tour organizers had avoided the term “pilgrimage”—it seemed so pretentious. But to a remarkable extent, these travelers had journeyed forth with pilgrim-mind, eager to use the change of scenery and the interruption of routine to listen deeply, to allow for shifts in the internal landscape.

I returned to New York with renewed enthusiasm for my work, and, with the Buddhabus in mind, wondered if the material for this issue would inspire people to look for teachers, visit centers: there’s a lucid dharma discourse by Bhante Gunaratana; Eido Carney introduces the Zen practice of takuhatsu, publicly begging for alms, in Olympia, Washington; Jan Chozen Bays explores what the Buddha taught about sexual harassment; three books on the Pure Land Buddhism are reviewed. So far, a nice flow with a rich mix: old and new, Asian and Western, men and women, Buddhas and Brancusis. But when we reviewed the designed pages in sequence, I suddenly felt caught in a crosscurrent, flailing between the special section on Buddhism and Twelve Step programs and the interview with Thinley Norbu Rinpoche.

From the inner lining of the Tibetan Nyingma tradition, with its emphasis on guru yoga, Thinley Norbu Rinpoche delivers a withering assessment of Buddhists in America. He ascribes our general resistance to spiritual surrender to a misguided understanding of—and an intractable attachment to—the iconic values of democracy and independence.

In Twelve Step recovery programs, on the other hand, more attention is paid to the necessity of surrender than is currently popular among new Buddhists. However, in Alcoholics Anonymous, spiritual surrender functions within a radically democratic structure. AA participants in a panel discussion speak of the wisdom of the group and the capacity of peers to function as the “higher power.” Equality, democracy—horizontal rather than vertical structures—remain the backbone of American idealism, yet nowhere in today’s society do they seem to work more brilliantly or more effectively than in AA. But what happens when we apply these cherished principles to Buddhism?

Back to Thinley Norbu Rinpoche: he says that’s not Buddhism. Disparaging a democratic sense of sangha wisdom, he affirms the vajrayana requisite for gurus as well as for faith in “a wisdom lineage” that is transmitted through successive generations. His views of lineage, karma, and reincarnation point toward a vast sense of time and space.

The effort to combine Buddhism with as American a paradigm as the Twelve Steps has its parallel in similar efforts among Buddhists working in such areas as psychotherapy and social activism. Do these collective efforts tend to embed the dharma in a view conditioned by topical—and therefore limited—values, and one predicated on a sense of linear time?

For Thinley Norbu Rinpoche, such a reductive scale dooms us to nihilism. Is he just defending the endangered species of gurus? Or is his censure a wrathful manifestation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, pulling us back from the brink of eternal darkness?

Many pieces in this issue will elicit diverse responses in the same way the Buddhabus tour did: some participants returned home committed to no formal practice, while others clarified an attraction to vajrayana or vipassana. But I’m wondering if the combination of material is itself beneficial, if the mix elevates the sum of its parts or diminishes them—or if it even matters.

In my own case, the crosscurrent has made me uncomfortable. Yet the spiritual friends and teachers, Asians and Westerners, who have helped me the most (including Thinley Norbu Rinpoche, whom I knew in the 1970s) made it clear that making me “uncomfortable” was part of their job. The lessons lay in paying attention to the friction, the tension, the anxiety—not between them and me, but between me and myself. Now I am left to pick my way between the East and the West, through the nasty thickets of personal psychology, conditioning, old and new methods to alleviate suffering, old and new kinds of wisdom teachings.

And what of my traveling companions? In a way every issue is a Buddhabus tour, a visit to different traditions, teachers, views, tasting the dharma in its many variations and perhaps finding a dharma home in which to settle down. For this tour too, a touch of pilgrim-mind can make a difference.