The Nechung Oracle, medium for both prophecies and warnings, has been the protector of Tibet since the eighth century. Today, the Oracle is a monk living in Dharamsala, who grows flowers and speaks perfect English.

I wander around my garden, stopping to look at some bright purple clarkias growing next to several stalks of barley. Both the seeds of the clarkia and the grains of barley were given to me by a gentle monk in Dharamsala, India, home of the Dalai Lama and thousands of Tibetans in exile. Like many Tibetans themselves, the tiny clarkia seeds from Lhasa in Tibet now flourish in an alien culture. I reflect upon their journey to my garden.

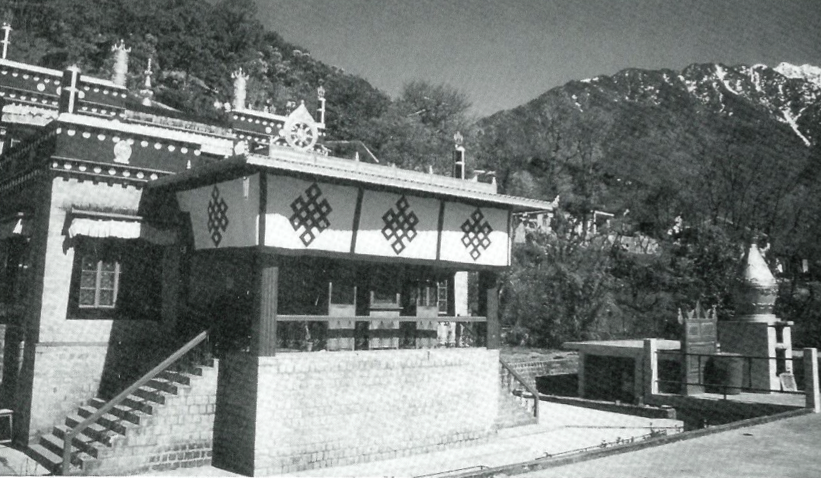

One cold early dawn shortly after the Tibetan New Year, I congregate with others outside the small Nechung Monastery, in the compound of the Library and Archives. We are here to witness the Nechung Oracle perform one of the first trances of the New Year. A monk leads us through a slide door, where we are seated on a wooden floor carpeted on both sides, while eleven monk musicians with tall yellow hats take their places in the middle facing a raised platform. In the background stands a large statue of a gold Buddha in a cabinet with long prayer books on either side, a photograph of the Dalai Lama, and deities in glass cases. In front of the cabinet stands a throne strewn with red robes. Incense and tormas, painted molded rice flour offerings, with khata, white ceremonial scarves, sit on a side table. A few prominent signs are stuck on the brightly colored ornate posts, proclaiming: “It is strictly prohibited to photograph the Oracle when in trance.”

The peaceful atmosphere is broken by hundreds of Tibetans clambering through the front door to experience this great opportunity of the Oracle going into trance. The doors remain open to allow as many people as possible to witness this occasion. (Although he goes into trance about twenty to twenty-five times a year, the event is not always a public one.)

When everyone settles, the Oracle, supported by attendant monks, is led in from an anteroom and seated on a stool. He places his feet firmly on the ground, and below several layers of voluminous, rich, brocade robe embroidered with Tibetan symbols in blue, green, red, and yellow can be seen long white brocaded boots with upturned toes. On his chest, like a breastplate, he wears a large polished steel- and gold-plated circular mirror surrounded by clusters of turquoise and amethyst. In the center is an engraved mantra, the first syllable of the name of the deity who will come through the mirror and possess him. He also wears a harness supporting four flags and three victory banners. Already in partial trance, his face appears a little crooked and puffy.

Four musicians blast their long horns, the others joining in with drums and cymbals. They begin to chant invocations and prayers, accompanied by the loud clashing of cymbals. The Oracle’s eyes begin to twitch, his mouth opens and he starts shaking. As the trance deepens, he begins to hyperventilate at an immense rate. The attending monks observe intently until he reaches full possession, then place on his head a towering gold-plated helmet adorned with jeweled skulls, peacock feathers, and silk banners topped with down. They work quickly and accurately to knot the strings under his chin, pulling them so tightly that it looks as if they will strangle him. (If they did not tie the twenty-kilo helmet correctly, or if the Oracle was not fully in trance, it would break his neck.)

As soon as the helmet is secured the Oracle begins to thrash his head backward and forward. He hisses violently, then jumps up and grabs a ritual sword and a bow and performs an ancient dance resembling the movements in ceremonial martial arts. He is now fully possessed by the wrathful deity Dorje Drakden. The Nechung Oracle’s role as protector of Tibet began in the eighth century when the first Oracle was appointed as the protector of Samye Monastery by Padmasambhava (“The Lotus-born”), historical founder of Tibetan Buddhism.

I am sitting next to a woman with a three-year-old girl, and although there are several other small Tibetan children and babies in the temple, nobody utters a sound. As the room becomes full of Dorje Drakden’s energy, more forceful hisses come from the oracle. He moves with the help of the monks and after about ten minutes is supported to the throne, where a monk-secretary seats him and starts to ask questions. Although it is difficult to hear, the Oracle answers with a shrill voice. The secretary quickly writes down the answers, while at the same time the members of the congregation are summoned to file past the Oracle to receive a blessing.

The crowd at the back pushes and strains to reach the Oracle. There are three steps leading up to the platform, and the monks have to restrain people from falling. As they pass by the Oracle, he dips his hand into a bowl and gives them each a handful of orange-colored blessed barley. As they are quickly ushered to the side door, a monk hands each one a red protection cord to be tied around the neck.

Now the people seated at the sides join in the lineup. It is taking too long, and the Oracle is collapsing. Suddenly he is lifted by two monks and is carried, corpselike, into the anteroom. With a strange tingling feeling and a heightened awareness, I leave the temple and linger with others in the bright morning sunshine.

The previous Nechung Oracle, Ven. Losang Jigme, gave the Dalai Lama specific advice on how to leave Tibet in 1959, telling him in trance consultation the exact time to leave Tibet and what route to take. He had suffered tremendous mental and physical problems in his early years before he became the Oracle, and even as he escaped he suffered crippling arthritis. After his arrival in Dharamsala the Dalai Lama’s physician cured him of arthritis.

However, the trances tend to affect the heart, and in 1984 he died of a heart attack. Shortly after Losang Jigme’s death, special prayers for the discovery of a new Nechung medium were composed by the Dalai Lama. These prayers were recited by the monks of Nechung Monastery, as well as at other religious centers throughout the Tibetan community. During the spring of 1987 the Drepung abbots, from Tibet’s largest monastery, were in Dharamsala, together with other high lamas and monks, to attend the teachings of the Dalai Lama. On March 31, they held a special ceremony at Nechung Monastery in front of the sacred statue of the State Oracle. During the ceremony one of the monks present, Thupten Ngodrup, spontaneously fell into a trance. He was then summoned to the Dalai Lama, who instructed him to perform a meditation retreat focusing on the tantric mandala of Hayagriva and many other rituals. Later, the Dalai Lama had Thupten Ngodrup perform a trance privately in his presence, where he tested him according to tradition.

On May 22, at Thekchen Choeling, the main temple in Dharamsala, Thupten Ngodrup made his first formal public appearance in the complete traditional costume of the Nechung Oracle before the Dalai Lama, members of the Tibetan cabinet, and a large number of high lamas and monks. On September 4 he was officially enthroned as the Fourteenth Nechung State Medium.

(The Dalai Lama has often been asked by scholars of Tibetan culture and progressive Tibetans why he still consults the Oracle. His answer: “Because his advice is always sensible, very good.”)

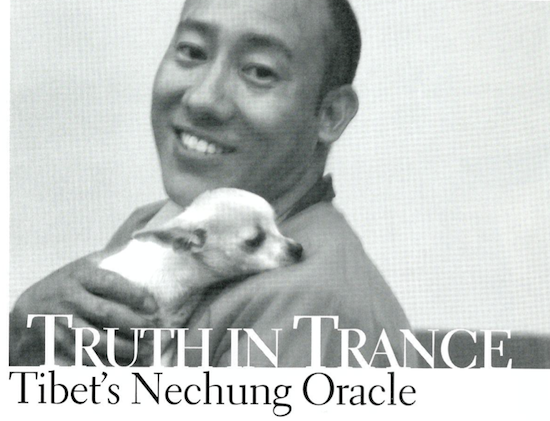

A few days after witnessing the trance, I visit the Nechung Oracle in his living quarters at the monastery. In the small, neat, flower-filled room where I wait, a picture of Gandhi occupies a dominant position on the wall. A diminutive monk enters and seats me at the table and in perfect English asks me my name and where I am from. He looks younger than his forty-two years, and it takes me a few minutes to realize that this monk with the calm, unlined face is indeed the Oracle.

Thupten Ngodrup was born in Phari, Tibet, near the border of Bhutan in 1957. From a very early age he had wanted to be a monk, but at that time the Chinese had destroyed many monasteries and it was difficult. He came with his parents and brother to India in 1966, and with the agreement of his father became a monk at age thirteen. He joined Nechung Monastery in 1971 and after undergoing rigorous training in the spiritual and artistic traditions of the monastery he was appointed the Master of Rituals.

He tells me that he is always very frightened and unhappy before a trance, and must meditate for two hours or more in preparation. However, after a trance he feels relaxed and happy. The first time he went into the spontaneous trance it felt like a huge electric shock, but now going into trance is like being on an airplane with much turbulence. He doesn’t remember anything that happens during the trance and doesn’t want to know. To keep his pure state, foods such as fish, garlic, and onions are eliminated from his diet. Although he takes care of his health, he says that being a medium is physically demanding, and he has had high blood pressure and some heart problems.

I find out that he is a keen gardener and during the long winters he grows plants in a greenhouse. I ask about the blessed barley and whether I am allowed to plant any. He tells me I can as long as I keep some of the grains for protection. He says to put them in bags when I travel and to burn some when I have difficulties in my life. He disappears for a few moments, returning with a little plastic package of seeds that he says comes from Lhasa.

He does not know their name in English, but tells me to plant them in my garden. I ask to take a photograph, which he agrees to. I frame him with the photograph of Gandhi and the white azalea he has grown, but the borrowed camera is stuck and nothing happens. He takes the camera and plays around with it but he too is unable to make it work. I arrange to see him again in a couple of days. However, when I arrive to take the photographs he has limited time, so I forego my plan to photograph him surrounded by the red and yellow Dutch tulips he has nurtured in pots. Later I meet my friend Tashi, and we leave Dharamsala to go on an outing to visit the Norbulingka Monastery (named after the Dalai Lama’s summer palace). At this beautiful monastery surrounded by lush Japanese style gardens, Tashi and I relax on a rock in the sun. Suddenly I look up to see walking toward me, down a path bordered by tall feathery ferns, the Nechung Oracle. He greets me with his broad smile exposing an even set of pure white teeth. Then, like the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland, the image of his smile lingers as he slowly disappears down the path.