In late May, two Hindu tantric priests from Gwalior, India, checked into the Yak & Yeti, Kathmandu’s leading hotel. Their expenses were covered by the mother of Deviyani Rana, the woman set on marrying Nepal’s crown prince, Dipendra Shah. Astrologers had already decreed that the stars were not favorable for their union, and the king and queen themselves opposed it. Deviyani, however, was adamant. “If this doesn’t work out,” she once said to a cousin, “I’ll be the laughing stock of Nepal.” Hindu tantric practitioners often claim the ability to alter destiny, and Deviyani’s parents had ample resources to recruit the best. The chosen rite was that of Bagalamukhi, a fearsome weapon-wielding goddess of Hindu tantrism. Deviyani’s mother had commissioned a painting of the goddess in the weeks before, sending it back repeatedly to add more implements and arms. One of her several hands wielded a club. Another clutched an enemy’s severed tongue between a pair of iron pincers.

By accounts of those close to the court, the king and queen got wind of these dark rites and recruited rival sorcerers. Many Nepalis now believe, in fact, that the Crown Prince was caught in the crossfire of tantric warfare. When he entered the palace billiard room on the evening of June 1, he carried more weapons than he had hands; guns were slung over his shoulders or strung from his sides. Without uttering a word, he proceeded to gun down his entire family, the obstacles to his union with Deviyani. The Queen Mother was sitting in a separate parlor but didn’t budge. “There he goes killing cats again,” she said to her companion, referring to the Crown Prince’s nocturnal penchant for shooting crows, bats, and other small mammals that frequented the palace compound.

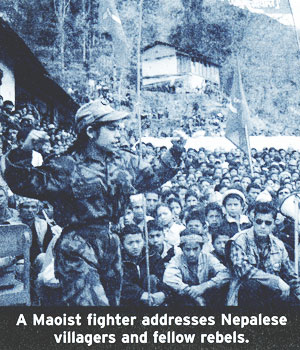

Fourteen members of Nepal’s royal family died in the massacre, including King Birendra, Queen Aishwarya, and the Crown Prince himself, from bullet wounds said to be self-inflicted. The tragedy could not have come at a worse time for Nepal. The kingdom’s foundering parliament was riddled with corruption scandals, and a Maoist insurgency born six years earlier in the impoverished hill regions was rapidly gaining ground. Rebels secured arms by attacking remote police posts, the death toll from their predations climbing to more than eighteen hundred since the insurgency began. Bolder forays in July led to an armed confrontation between Maoists and the Royal Nepal Army, poising the country on the edge of civil war.

A new prime minister, elected into office in August, initiated a cease-fire with the Maoists on the first day of his appointment and began a series of “peace talks.” The negotiations reached an almost immediate impasse; the Maoists were demanding a new constitution and the establishment of a republic in place of the current constitutional monarchy. In deference to Maoist sensibilities, however, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba proposed a land redistribution act that set a limit on the ownership of land. The presumptuous move was later retracted since it crippled the economy and panicked Nepali banks, whose loans are primarily secured by land. The proposal also led to a surge in divorce petitions when couples sought to secure their current holdings by dividing property.

Although the Maoists talk about their “dharma,” their “People’s War” has transmuted into a Taliban-like crusade against common sense. Maoist leaders have sought to ban the production and sale of alcohol, beer, and tobacco, which, after tourism, provide the government with its largest sources of revenue. These funds are desperately needed for developing the remote areas of the kingdom where revolutionary sentiments first emerged. In addition to depriving the government of needed taxes, the Maoists’ ideological war against “vice” has been oddly advanced by an escalating campaign of terror and intimidation. Distilleries have been blown up, and in mid-September an armed Maoist-aligned student union forced the closure of all schools in the Kathmandu Valley and lobbed Molotov cocktails into two empty school buses parked outside Nepal’s most extensive library.

The government has expressed its commitment to a negotiated settlement, but the Maoists have, so far, been unwilling to compromise. Their leaders have said they will return to their armed struggle and “violent retribution” if their demands are not met. In one ill-considered statement, they even said they might do to the Royal Palace what terrorists in the United States had done to the Pentagon.

Increasingly, the Maoists have financed their insurgency by extracting “donations” from businesses and educational institutions in the Kathmandu Valley. For a mass rally planned for September 21, they demanded that thousands of their party workers be given free room and board in boarding schools, hotels, and Buddhist monasteries. In the wake of the terrorist attack on the United States, however, few urban Nepalis have expressed sympathy with the Maoists’ hardline rhetoric and continued zeal for violence. A week before the mass rally, thousands of Kathmandu residents turned out for a peace march, which—along with new government regulations banning demonstrations—led to Maoist leaders postponing their planned gathering in Kathmandu.

When the heads of Buddhist monasteries in Boudha and Swayambhu met to discuss whether or not to cede to Maoist demands for food and shelter, they decided against it. Their rooms were already full of monks—many of them refugees from Communist oppression in Tibet—and complying with the Maoist demands was viewed as an implicit support of their ideologically motivated violence and depredations. Good relations nonetheless exist between monks and Maoists at Buddhist retreat centers such as those at Namobuddha outside the Kathmandu Valley, which employ local villagers and offer free medical care at the monasteries’ health clinics.

As refugees on Nepalese soil, Tibetans are barred from all political activity that might disgruntle China, Nepal’s mighty neighbor to the north. Indeed, Nepal’s recently renewed diplomatic and economic ties with Beijing, and the Ministry of Tourism’s efforts to promote Nepal as a destination for Chinese tourists, make many Tibetans here feel uneasy.

While traditional Hindu and Buddhist astrologers (who largely rule the national psyche) are noncommittal regarding the country’s future, Buddhist monks offer prayers for peace in Nepal’s many monasteries. Many Nepalis and Tibetans have lost confidence in their country’s chances for resurrection, however, and are looking for a ticket out. The visa lines in front of foreign embassies grow ever longer. Some of those standing in line are Tibetan monks—or men dressed up as monks—hoping for religious visas and jobs in the West.

Amid the uncertainty, Nepalis and Tibetans alike find solace in Buddhist teachings on impermanence. Some Tibetan lamas take a positive view and remind their students that chaos and negativity offer fertile ground for practice. They joke that, with business down, it’s an ideal time for contemplative retreat. Either way, if the usual hordes of tourists who fuel the country’s economy fail to arrive during the fall trekking season, Nepal could well turn into a social and economic charnel ground, a replay of the lawlessness of China in the 1930s.

I recently visited a Nepali friend—a hydrological engineer—who kept a painting of the goddess Bagalamukhi on his household shrine. The image revealed her in a particularly malevolent form, seated on a corpse. I mentioned the persistent rumors that insist that the Crown Prince and those he killed were inadvertent victims of her arcane rites.

Bagalamukhi, my friend said, is often worshiped to “paralyze” the movements and activities of enemies, to attract them, bring about their death, or to counter the influence of ill-aligned planets. She is also invoked, he said, to heighten sensibilities and grant wisdom, knowledge, and liberation. Tantra is power, he insisted, and like all power it can be easily corrupted.

Turning the conversation to Nepal’s current political plight, my friend held that the best thing for the country would be to put the Maoists in power as soon as possible. That way, he said, their followers would discover that they’re no better than the rest, and their reign of terror could be brought to a halt. He went on to emphasize that, worshiped correctly, Bagalamukhi—like other Hindu tantric goddesses revered in Nepal—could bestow endless boons. For this to occur, however, one had to give up all hope of personal gain.

As I walked home through temple courtyards and past roadside shrines, I reflected on the esoteric and paradoxical lore that still shapes the culture and politics of Nepal. Opposite the gates of the royal palace, the site of the Crown Prince’s carnage, an elderly Tibetan woman was holding aloft a cage of birds. In an ancient Buddhist rite inviting freedom and renewal, she opened the cage door, and a flock of bright green parrots ascended into the darkening monsoon sky. ▼