In the last years of his life I visited Rick several times at the home he shared with his wife, Marcia, in Northern California. Often I would spend a week with them, tagging along to attend Buddhist teachings, eat lunches with friends, go to the hospital for chemo, or take long, slow walks through the redwoods—the day-to-day activities of an American Buddhist writer living with cancer. There was a sense of extraordinary openness in the way that he faced everything, from something as ordinary as eating breakfast to the most complicated aspects of life and death. To some extent I had always seen this openness, this simple but solid presence, in Rick; but in those final years when he was facing death so directly, it seemed to truly blossom.

The silent presence of death also brought a sense of clarity and calm to these visits. There was not really anything to do, beyond enjoying the time together. These visits always seemed long and slow until suddenly, one morning, it would be time for me to go. Each time, on the way to the airport or bus station, the strange thought that this might be the last time I would ever see Rick would sneak into my mind. The thought that whatever farewell I uttered might be my last words to him had a paralyzing effect on me. What could I possibly say to this man? He was my greatest teacher, my closest friend; he had been a source of inspiration for longer than I could remember. Usually, a long embrace pulled me out of this futile search for the right “last words,” and there was always the hope, even the prayer, that I would see him again.

At those bus stop good-byes I had always noted in my mind what Rick had said in the hope that one day these “last words” would hold some profound meaning or final teaching. I would turn them over in my mind, staring out the window at the blurred landscape, and usually I concluded that these were definitely not Rick’s real last words. He was certainly expecting to see me again, or he would have said something more enigmatic and profound. Yet this vain hope for some “final statement” went directly against everything that Rick ever taught me.

As one does with any teacher, I often went to Rick looking for answers. I don’t think he ever gave me a single one. Yet, I’ve never met anyone who took my questions so seriously. Rick was so thoroughly engaged in examining and exploring questions that he didn’t seem to have time for answers. Whether I was a thirteen-year-old asking him about God or a sixteen-year-old begging for stories of beatnik heroics; an eighteen-year-old demanding to know exactly what “this emptiness thing” was all about or a twenty-year-old asking for advice on what to do with my life, Rick would guide me into the heart of the question, never trying to find a way out of it. This was often incredibly frustrating, but in his absence, there are few things I miss more than his ruthless insistence on trying to see a situation as clearly as possible, without the distortions of egocentric fantasies or static dogmas. For Rick, the questioning and examining were really the whole point; an answer was usually a reductionist refusal to keep looking.

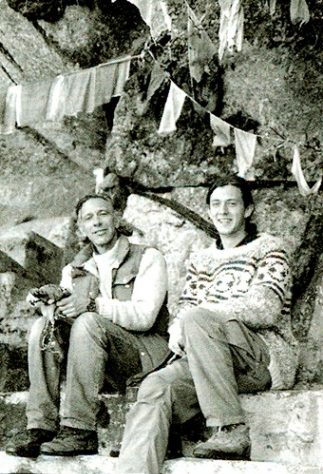

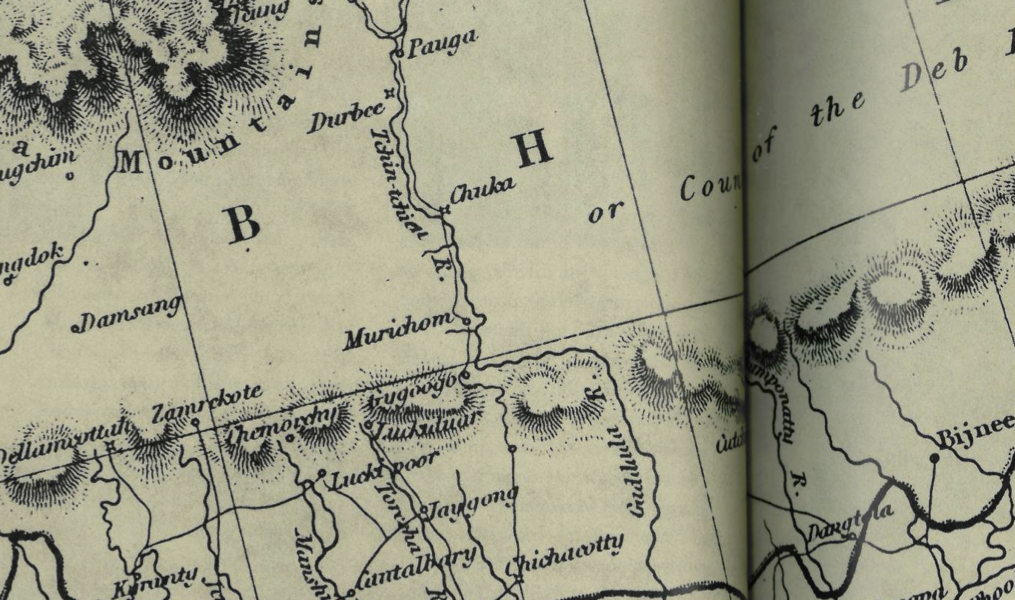

When I was eighteen years old, Rick and I spent a month traveling together through India and Nepal. At the center of this trip was a pilgrimage to sacred Buddhist sites in Sikkim, known to Tibetans as Beyul Dremajong, the Hidden Land “Rice Valley.” In the eighth century, Padmasambhava, the founder of Tibetan Buddhism, blessed this land as a secret refuge for the practice of dharma. According to some, the hidden land will be opened by a prophesied master in the future, when the Buddhist tradition is in danger of persecution and extinction.

According to others, for those whose perceptions have been purified of self-centered distortions, Sikkim already is a Buddhist paradise, its mountains covered with miraculous images that spontaneously appear and its rivers and skies the abodes of countless celestial beings. On our way to this hidden land, Rick took me to meet his guru, the great dzogchen master Chatral Sangye Dorje Rinpoche. When Rick explained that we were “going around the sacred places” of Sikkim, Chatral Rinpoche nodded and smiled. He looked across the low table beside him and picked up a ballpoint pen, rolling it between his fingers and examining it with incredible attention. Then he quickly wrote the names of four sacred places on a slip of paper and handed it to Rick, instructing us to visit each of those sites and recite the Seven Line Prayer to Padmasambhava continuously:

In the northwest of the country of Oddiyana

Born on the pistil of a lotus:

Endowed with the most marvelous attainment;

Renowned as the Lotus-Born (Padmasambhava);

Surrounded by a retinue of many Khadros

Following you I practice:

Please come forch to bestow blessings.

In Gangtok, Sikkim’s capital, Rick had the small slip of paper laminated. In a roadside teahouse we planned out the route (by bus, jeep, and foot) that would take us to each of the four sites. Over the next few days Rick taught me the words of the Seven-Line Prayer and we sang it continuously in Tibetan as we walked. We visited caves and monasteries, small village shrines and impressive old temples, all the while chanting our seven lines over and over again. By the time that we started out for Yoksum, the final of the four destinations in Charral Rinpoche’s very condensed pilgrimage guide, the words of that prayer had replaced conversation. The same Tibetan syllables that I had awkwardly forced into shape during the first few days now seemed to come to my lips naturally, as if their repetition was an integral part of the act of walking. When we reached the stupa that marks the legendary meeting place of the three Tibetan masters who established Sikkim as a Buddhist kingdom, we walked around it in slow circles, singing the seven lines.

The bright January sun was low in the sky and cast an intense golden light across the fields below the stupa. I sat down beside Rick and smiled: we had done it, our pilgrimage was complete. Rick stood up. Looking around at the forest-covered mountains behind us, he excitedly suggested that we keep walking. Yoksum was not only the last spot on our pilgrimage, but also the last spot on the motorable road. North of Yoksum there is only forest and mountain. Rick’s eyes glimmered with youthful excitement as he pointed our that this was our chance to see what there was beyond the end of the road. Exhausted from the long walk, I looked up at my fifty-three-yearold uncle in disbelief. I feebly tried to point out that the sun would soon be behind the mountains. We would be cold and hungry. He looked at me, his eighteen-year-old nephew, with even greater disbelief. I stood up and we started walking up the trail, past the end of the road. The path wound steeply up through a thick pine forest of incredible beauty. I followed as Rick walked on, quietly singing the seven lines. My whole conception of the pilgrimage, my careful calculations of how long it would take to reach each of the four sites, all fell to pieces. The narrowness of my notion that our pilgrimage was finished was laid bare by Rick’s exuberant insistence on seeing what was beyond the end of the road.

Eventually we both needed to stop for a rest, and we sat on two flat rocks looking down over the valley in the crimson light of evening. Then we heard a noise. Both of us sat upright in silence, trying to discern the barely audible sound. Slowly, the hauntingly beautiful song of an old woman became clear. Rick smiled and said, “Here comes a dakini.” Eventually we saw her approach, effortlessly carrying a large jug of water up the mountain that I had just sttuggled to climb. She smiled when she saw us and took Rick’s hand. She did not stop walking or singing, but led us to her house and the small shrine that she tended. I listened carefully to her song as we offered prostrations and butter lamps before a statue of Padmasambhava. The only word that I made our was Dewachen, “Great Bliss,” the name of the pure land of the Buddha Amitabha.

When I remember Rick I often also remember the song of the dakini beyond the end of the road. I remember that in the presence of his remarkable openness, the ways that I divided and defined my world, the beginnings and the endings, were often revealed as arbitrary attempts to find answers rather than explore questions. Now, I remain filled with gratitude for the way that he pointed beyond.