Into the turn-of-the-century splendor of New York City’s National Arts Club strides Michael Roach, carrying with him 30,000 pages of Tibetan Buddhist sutras—and $20,000 in diamonds. Roach has chosen the club’s stately, mahogany-paneled dining room as a meeting place to discuss his plans to digitize the dharma. He’s barely in his chair before he switches on his Powerbook to demonstrate the latest release of the Asian Classics Input Project (ACIP), an organization he founded that employs about twenty young monks in India to type the Tibetan canon onto CD-ROMs (computer disks). After a few moments, one thing is clear: Michael Roach is not just a simple Buddhist monk.

Dressed in a gray business suit and tie, rather than the yellow and maroon robes he wears at his monastery in Howell, New Jersey, Roach, forty-one, looks like a savvy businessman. The project, he explains, was started in 1989 with a number of longtime friends: Robert Taylor, John Malpas, Dieter Gewissler, and Steve Bruzgulis. For seed money they used the earnings from Roach’s work as a diamond dealer and a grant from the Packard Foundation. Subsequent funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and other sources has already facilitated the production and release of three sets of disks containing a total of 30,000 pages of text. Roach’s aim is to put the entire Tibetan canon onto CD-ROMs in transliterated Tibetan and then to issue those same texts in English translations. An optimistic estimate for the completion of phase one is forty years. Since it took seven hundred years to translate the Buddhist canon from Sanskrit into Tibetan, the English version—he figures—may well take a century or two.

To produce a finished disk, each text must be entered twice, then run through a computer to check any differences. Finally, each disk must be proofread, checked, copyedited, proofed again, and authenticated by a lama. Although the work is time-consuming and costly, completed disks are distributed for next to nothing. (The suggested donation is $15 for all 30,000 pages.) This is done both in consideration of dharma ethics and as a response to the changing nature of information: “Once something is digitized, you can’t protect it. How do you prevent it from being put on the Internet? Do you want to prevent it? True knowledge should be spread. When the electronic highway has entry ramps from every home, you might as well grin and give it away—which is what we’d like to do anyway.”

The success of ACIP can be attributed not only to Roach’s commitment but also to the cooperation of the Tibetan Buddhist community. He credits their enthusiasm, in part, to their desperate situation: “If the devastation hadn’t occurred, very few people would have been allowed into Tibet. Tibetans were very stable and would not have needed any help. Without their current poverty this project probably wouldn’t have happened.”

Roach hails computerization as the best way to preserve and distribute dharma, but, he adds, it is also an unparalleled teaching tool. Pointing to his laptop, he notes that it contains more books than any single monastery. Furthermore, these works can be cross-referenced with ease: research that took three days in a library can now be achieved by pressing a button. And interactive hypertext essays—which are electronic concordances, dictionaries, and encyclopedias all rolled into one—allow students to take sutra study at home to a new level. The first interactive essay created by ACIP is color-coded: synonyms are in green, yellow indicates that biographical information is available, and red means the original appearance of a term can be accessed. If users click on “suffering” (in red), for example, the computer calls up the first canonical definition. Roach would also like to produce high-quality Buddhist multimedia programs that will combine a text, the voice of a master chanter, and movies to illustrate mudras.

Related: Obsession and Madness on the Path to Enlightenment

From his monumental plans, Roach quickly switches gears. With a gracious flourish, he removes two diamonds, valued at $10,000 each, from his breast pocket. One is flawless. He holds it up to the light and examines it. A moment later he whisks out another, identical diamond as a souvenir of our meeting: it’s a perfect fake. Only a dealer’s electronic heat-sensor can tell it from the real thing.

Nearly every diamond sold in America passes through 580 Fifth Avenue, a building in the heart of New York City’s diamond district. There’s a Brinks office and a post office inside; huge diamond-filled vaults occupy the basement. It also houses the Diamond Club, a members-only establishment where freelance diamond dealers gather to do business. Like the diamond trade itself, the club is run predominantly by Hasidic Jews. All dealing is done on trust—if problems arise, complainants are referred to a rabbinical council in lieu of law courts. For that reason, all members must have a million-dollar bond put up on their behalf. It took Roach more than three years to get in. His boss put up some of the money; the rest was transferred by friends and relatives to his bank account for a single day to register the minimum balance.

We wait to get clearance from uniformed guards behind bullet-proof glass. In a sea of payess and black hats, Roach’s uncovered head stands out; there are approximately 150 people in the room and he is one of about fifteen who are not Hasidic. As soon as we pass through the turnstile, he begins to deal. Greeting someone he knows, Roach inquires about a large marquise. Someone looking to buy broken diamonds approaches him. After the man moves along, he whispers, with a hint of mischief, “I am recutting them but didn’t tell him.” The broken chips are sent to a factory Roach donated to Sera Mey monastery in South India, where he has taught the monks to recut the stones. Since the monks have only a labor cost with no overhead, they turn a respectable profit. Otherwise, Roach says, the operating expenses would be enormous: “For the packages of rough diamonds offered by De Beers, you have to put down a million-and-a-half dollars. Cash. Those are the conditions to go to the store and buy.”

On white plastic tables stones are unwrapped and gingerly removed from the folded robin’s-egg-blue paper. Dealers haggle over quality, color—”It’s yellow,” and, “No, it’s champagne”—and price. Although Roach takes obvious delight in the art of the deal, what brought him to diamonds was a vision. The diamond, he says, is the symbol in the natural world that is closest to emptiness, a fundamental Buddhist concept about the nature of reality.

His eyes become slightly hazy and out of focus, as they frequently do. The meaning of the diamond seems something secret, or at least incommunicable. The booklet Roach wrote to accompany the release of ACIP’s third set of disks, however, sheds some light:

It is interesting to note that the word “diamond” occurs nowhere in the Diamond-Cutter Sutra except for the title. And yet the title itself contains perhaps the most profound message of Asian philosophy, which is fitting for the oldest book in the world. Diamond is the closest thing to an absolute in the natural world: nothing in the universe is harder than diamond; nothing can scratch a diamond. Diamond is absolutely clear: if a diamond wall were built around us we would not be able to see it, even if it were many feet thick. In these senses diamond is close to what Buddhist philosophy terms “absolute truth,” or emptiness . . . Subsequent to seeing absolute truth directly, we understand that reality as we normally experience it, though valid, is something less than absolute. All objects possess a quality of absolute truth, or emptiness: all objects are void of any self-nature which does not depend on our projections. In this sense we are surrounded by absolute truth, but have never been able to see it: it is as if this level of reality were like a wall of clear diamond.

Next to the main dealing room is a smaller, square room reserved for retired dealers. They, too, are grouped around tables but this time all they are dealing is hands of poker. Set off from that room are the prayer room and the cafeteria. Over a Jerusalem bagel, Roach explains that following his vision, he sold his car, took the money, and walked to a jeweler’s, where he bought a diamond for the Dalai Lama’s tutor. He then hired himself out as a diamond messenger, and eventually helped build up the company from a staff of two people to eight hundred. Curiosity, rather than ambition, motivates him: in his spare time he has trained to buy diamonds in the rough (a skill he tested out in the South American jungle), and recently he bought a mount so he can cut diamonds at home—it’s what he does to relax.

For many years Roach did not tell anyone at work that he was a monk: “It’s good to be around ordinary people. And in jewelry you get greedy people, beautiful women, backbiting, everything.” This, he says, has proved a boon to his translation skills: “Before this I was living either in the university or in a monastery and never had to communicate with ordinary people.” He also credits his increased effectiveness as a fund-raiser to his job: “Classic business is where the deal helps each party: mutual profit. I try to do that all I can.”

As he smiles, the light catches a diamond implanted in his tooth. Roach says he had it put there (in an upper bicuspid) to remind him of his vision and to remember that “this diamond will outlast me—the bone and the skin and the blood. People will want to use it after I’m gone. We have a joke that it will seek a new owner.” His aspiration is fierce: “If I could put a diamond in my forehead I would. If I could put one where I would always see it, it would be useful. That’s the only important thing. I would tattoo the Heart Sutra all over my body—no kidding—but after a while you wouldn’t even notice that. Human nature is funny.”

Raised in Arizona as one of four brothers, Roach excelled in school, received a medal from Richard Nixon at the White House, and went on to Princeton in 1971 as a Presidential scholar. His plan was to study religion and become an Episcopalian minister—something, he adds, that was not in vogue in the early seventies. In other respects, though, he was a typical student, making money as a bass player and getting arrested in demonstrations against the Vietnam War (during which time he returned his medal to Nixon in protest). “What attracted me to Buddhism,” he says, “was not what you’d expect—it was the approach to personal relationships. My parents were divorced in a rough way, and it was traumatic. A Buddhist principle is that the seed of the destruction of the relationship is born when the relationship is born; it doesn’t require an outside force to destroy any existing object, it’s simply their starting which destroys them. And I saw that relationships, no matter how nice they might be, would always fall apart—and that’s a Buddhist principle, impermanence.”

His first class in Buddhism was taught by Professor William LaFleur, whose memory of Roach remains vivid even after twenty years: “A lot of students in those days had an interest inspired by drugs, but not Michael. His mother was dying and he really wanted to find out what was what.” LaFleur arranged for Roach to get a fellowship to study in India for a year, where he worked at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. Roach says, “You have to notice sooner or later that there’s no future in anything aside from spiritual development. You can get up to vice president and die, or get thrown out and die. I did that. I went through a whole company up to the top, and what do you do after that? Whether it’s your house or your wife or your kids—there’s no future in anything.” Within his first year of studying Buddhism, Roach lost his mother, his father, and one of his brothers.

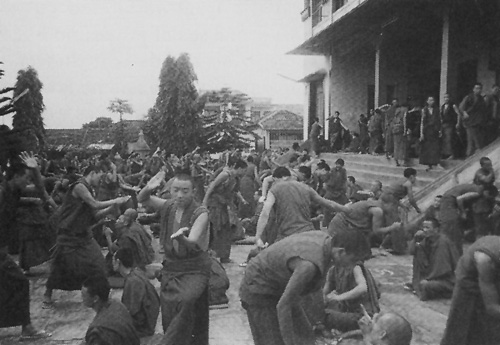

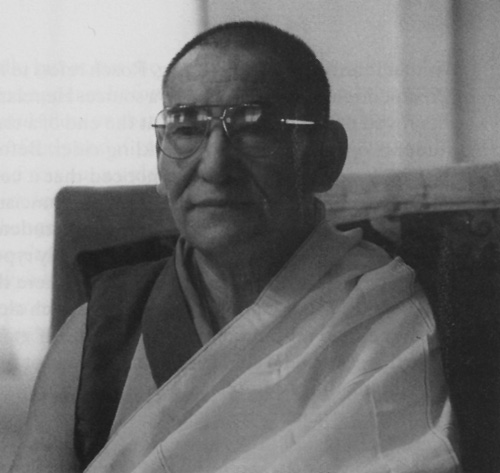

After Roach returned to the States, he went back to Princeton to finish his degree at the suggestion of the Dalai Lama. On his last day of class in 1975, LaFleur gave his Firebird to Roach, who drove it to the Kalmyk Mongolian monastery in Howell, New Jersey, in order to study with the abbot, Khen Rinpoche. When Roach arrived, recalls Khen Rinpoche (whose full name is Geshe Lobsang Tharchin), he brought with him some momos, or Tibetan dumplings, that he had made as an offering. Khen Rinpoche later confessed that he had to throw them away in the forest; they were awful in every respect—texture, taste, color. Smiling, he describes what Roach first said to him in his then rudimentary Tibetan: he meant to say “I want to study Buddhism,” but what he said was “I want be Buddha.” Now Roach is close to completing the sixteen-year geshe course (the equivalent of a Ph.D.) and is distinguished among his fellow students by being one of the few chosen to represent his monastery in the prestigious month-long Winter Debate, held this year at Sera Mey. The debating goes on all day, rain or shine, in a courtyard packed with pairs of monks arguing refined points of Buddhist logic. Roach is one of a handful of Westerners ever allowed to participate in the debate and the only Westerner in the five-hundred-year history of Sera Mey to qualify to take the geshe examination.

Roach relishes debate as an opportunity to finally apply the logic he has studied for the last fifteen years to vital questions, such as the provability of reincarnation: “It’s like the Olympics. Your teacher is like a basketball coach; you can learn six months’ stuff in one month. The atmosphere is intense.” Based on logic alone, argues Roach, people can find the motivation to study and practice Buddhism: “Buddhist logic is very important. You’re not allowed to accept something out of belief. You must be able to prove it. That’s great.” And while the subjects of the debates were chosen to counter schools of Indian thought that prevailed at the time of the Buddha, they address the same questions that an average Westerner would ask a teacher now. “For some reason we’ve cycled around,” he says.

Roach holds classes in and around New York seven days a week: in addition to debate, he teaches two sections of a five-year “baby geshe” course—one in English and one in Tibetan. Attendance requirements are strict; any student missing more than two sessions is out. One class, held on Friday night, is for the sometime student; about twenty people gather in an apartment on the Upper West Side for a six-week study of death meditation. When Roach arrives straight from the office, he takes off his shoes and tie and sits cross-legged on the couch. He starts off by saying that death is the only certainty and looks around the room. “One of us,” he says, “will be the first, and then someone will be the second.”

As we go through a Tibetan text, he encourages a few of his students who have been studying Tibetan for only a few weeks to pronounce the syllables aloud. Roach pushes them, correcting, cajoling, and complimenting until he gets a good performance. His rapport with each one—newcomer and longtime student alike—is excellent. Considering that he has been teaching for more than a decade—he held classes in his tiny, hotel-size room at the Princeton Club for eleven years—this is not entirely surprising.

During the course of the class, Roach invokes the Kadampas, tenth-century Tibetan converts to Buddhism who, after the decline of Buddhism in India, took on the exposition of the traditional writings as their primary task. He offers their drive and commitment to the teachings as an example for modern students to emulate. We too, he says, are in an era when Buddhism is in decline, and we must stir a sense of urgency in ourselves to keep the dharma alive: “What has happened to Tibet and to Buddhism in the world? It’s gone in China, basically gone in Taiwan, gone in Hong Kong, destroyed in Vietnam, repressed in Burma, gone in Laos and Cambodia. The strong Buddhism, that is. Thailand has only forty volumes of scripture; Tibetans have hundreds.”

Without interrupting his teaching, Roach refers to his Powerbook often, to locate a date or a source. He relates how it proved useful recently, when at the end of a class his students opened a bottle of sparkling cider. Before any cider was consumed, someone noticed that it contained 1 percent alcohol. For Roach, a strict renunciant, nothing more needed to be said. When his students pleaded that the amount was negligible, he simply typed in a search command and found the instance where the Buddha teaches his disciples not to drink as much alcohol as can be held on the tip of a single blade of grass.

While this search-and-find feature might prompt fundamentalist readings of texts, Roach’s concern is the opposite: that the computerization of the sutras will allow people to find the one instance where the Buddha says it is permissible to do something, and take those words out of context. He also worries about tantric material being released without regard to the correct context and the attitude of the practitioner. The computer screen goes blank when it comes to a tantric section on an ACIP disk and a message flashes up asking the user to contact the project. If readers have the proper initiations, they are directed to appropriate sources.

The bus to the monastery in Howell, a small town in central New Jersey, stops on the highway, next to an adult video outlet. Down the road just half a mile, the temple comes into sight. To its right is a small house containing a prayer wheel; plastic flowers adorn vases on the window ledges, and a well-worn circular path is visible in the wooden floor. Behind the temple is the main house, where Roach lives with Khen Rinpoche and Jampa Lungrik, a monk who has just arrived from India. Roach only spends four nights a week here, although he wishes it were more. Of the split between New York and his monastery life he says, “I don’t know of any monk who has succeeded who hasn’t been in a monastery. I think it’s difficult, very dangerous.” Because his lama “won’t make a monk easily,” Roach became a monk in 1983 but lived like a monk for ten years before that, “just to be sure.”

Roach is eager to demonstrate the interactive hyper-text ACIP has created. When we start up the computer in the main house, an elaborate colored prayer wheel appears on the screen, spinning slowly. Entitled “The Marriage of Morality and Emptiness,” the essay is designed to let a user investigate different meanings of emptiness and its relationship to morality. The computer, however, is not cooperating. As we wait to work out the technicalities, it becomes clear that Roach’s expertise is in dharma, not digital know-how. Without waiting for any help from the computer, he launches into a description of emptiness: “The person at work who is trying to get the boss to think I’m bad is truly hurting me. It’s nonsense to say it’s just empty or that it’s not happening. But his wife loves him, and people will swear he’s a great guy. You cannot be good and bad at the same time. It’s impossible; therefore he’s empty. If he were self-existently bad, his wife would hate his guts. If he were self-existently good, I would love him. That’s a proof in a few sentences that he has no nature. So where is it coming from? It’s my perception.”

Roach’s enthusiasm is for the time-tested rather than the newfangled. As our electronic standstill persists, he carries on posing questions, pausing for a beat, and then answering them. “According to Buddhism, the way karma is carried is through perceptions. When you react with hatred, even if you don’t say anything or do anything you’ve already caused something bad. Now the guy in the office is very real. So how does it help me that he is empty? What is the logical thing to do? Respond with compassion and love. Not out of any nobleness but out of self-interest, enlightened self-interest.” He goes on urgently, persuasively explaining that if we understand emptiness, we will—logically—act morally, compassionately: “If you have the slightest bad feeling about this guy, you’ll see yourself meet him again. That’s morality. So morality and emptiness are married.” It’s hard to imagine that the computer will make things any clearer than this straight-from-the-hip talk, but at last the machine responds: colorized, coded text appears before us. As I start to read the screen his words flow unabated: “If you understood his emptiness perfectly and if you went to work tomorrow and he was bad to you, would it be less painful? Could you make him less bad by understanding? No, it’s not going to change his nature. If you understand his emptiness, it won’t make him less bad. Don’t expect it. But eventually it will. He can only change because you can be good, over time. Because New York is empty, all New York can change—for you.”

Related: What’s in a Word?

Living With Technology

In 1989, I began to work with Michael Roach on setting up a data entry project at Sera Mey monastery in South India. Traditionally, to print a book, a monastery hired an artist to carve a woodblock “plate” for every page. When Ser Mey was forced to relocate after the Chinese invasion of Tibet, most of their plates had to be left behind, and were later burned. What survived was at best a few copies of each book, hand-printed on something that looks like rice paper. Because there are very few complete collections of the Tibetan canon, and few scholars capable of editing the material, the continued existence of this literature is threatened.

Our intention was to introduce the new technology into Sera Mey so that it could serve the monastery’s purposes—specifically, the production of books. But at the beginning, it was not clear whether the technology would fit easily into this unique culture, or if people at the monastery would perceive the advantages of computerization in the same way we did.

Five years later, ten thousand disks have been distributed to dharma centers and scholars in fifty countries. There are now similar computer facilities at seven Tibetan monasteries in India, which have been able to produce crisp new laser-printed versions of their own textbooks, replacing tattered, faded photocopies. Moreover, the monasteries have received compensation for their participation in the projects, and more than thirty monks are now employed typing in the books. If a cultural transition is in progress, these people are at its leading edge.

Some of the same Tibetan monks who had been at the monastery during the first years of the computer project now live at ACIP’s central office in Howell, New Jersey. All of them are either graduates of or currently enrolled in Sera Mey’s geshe degree program.

Ngawang Thupten, now in his twenties, came to the U.S. a year ago. He remembers an inspirational talk that Roach gave the first group of computer trainees, in which he mentioned that this project would help the monastery. Ngawang told me in Tibetan, through a translator, “We took his words for true. We put them in our hearts. That is what kept us going.” At the beginning, Ngawang, a data-entry operator, and the other young monks had no idea what they were supposed to do: “Other people assigned to work in the kitchen or the store knew what to expect from their jobs; we didn’t.”

According to Ngawang, the project altered the young monks’ perception of their own books. They understood that whoever had the disk had the book. “We thought if we did this work, the books could be stored in a compact way, and spread around the world.”

Jampa Lungrik, another young monk, commented that the computer project has very strict rules compared with other jobs at the monastery. Once accepted into the project, a monk must work four hours a day, five days a week. If he is ten minutes late, he is counted as absent, and not paid for that day. No other enterprise at the monastery operates on such a rigid code. And Ngawang Thupten added that he thinks the strict rules are necessary. At the monastery, in the Tibetan tradition, and especially in India, he explains, “there is no specific time for anything. The schedule was very difficult for us at first. Our minds were not ready for it. It was very uncomfortable. “

Geshe Lhundup Sherab, now in his late thirties, entered the project as manager without knowing anything about computers. He realized quickly that if the aim of this project was truly to preserve all of the books being burned in Tibet, then his responsibility was huge. If they could preserve not only the books at Sera but also books from other locations, and then send the disks around the world, this would really be protecting the teaching. He tried to impress on the young monks that typing in a scripture was a dharma activity not unlike studying and debating. He told them, “If you debate or study, the effects of those activities accumulate until you become a geshe many years later. But if you type in twenty pages of a book, it will be preserved for eternity. You have already done a complete Buddhist activity that will help all beings now and in the future.”

Although he anticipated that many older monks at Sera would resist computerization, Geshe Lhundup Sherab said that they were actually in favor of it. The monks remembered how difficult it was to reprint the monastery textbooks when Sera was first relocated. At one point they printed them using a crude form of lithography: they wrote the text on a flat stone, using a mixture of cow urine and charcoal as ink.

The image of the dharma being spread throughout the world through the medium of disks emerges consistently in the words of the monks. It is reminiscent of a Tibetan ceremony in which prayers are written on thousands of pieces of paper, and the papers are released into the wind as a metaphor for spreading the teaching. Both Geshe Lhundup Sherab and Ngawang Thupten found their own motivation for participating in the project when they realized that many other people would benefit from their work. They have clearly assimilated two important aspects of information-age culture: the duplicability of data and the ease of its distribution.